The Electronic Intifada New York City 7 November 2012

Filmmaker Arnon Goldfinger and Edda von Mildenstein in <em>The Flat</em>. (Zero One Film/A Sundance Selects release)

Arnon Goldfinger’s 2011 documentary The Flat has just opened in New York City. Although enthusiastically publicized as an unpredictable and astonishing trip into buried history revealing unpopular truths about the Israeli past, The Flat — or Ha-dira in Hebrew — ultimately fails to deliver on its proclaimed promise.

Instead, the film adheres closely to the acceptable parameters of Zionist discourse, offering little to challenge prevailing conceptions about the film’s ostensible focus: the controversial relationship between Zionism and National Socialism.

The Flat follows Goldfinger’s quest for answers after he discovers that his late grandparents, Kurt and Gerda (née Lehmann) Tuchler, maintained a close and long-standing friendship with high-level Nazi propagandist Leopold von Mildenstein and his family. The quest begins as Goldfinger and his mother, Hannah, find copies in Gerda’s former apartment of the notorious Nazi Party Berlin newspaper Der Angriff, in which a series of articles appears under the title “A National Socialist Goes to Palestine.”

The articles are written by von Mildenstein and describe his exploratory trip to Palestine in 1933 accompanied by his wife and the Tuchlers, Jews who would later emigrate from their native Germany to Palestine.

Zionist mission

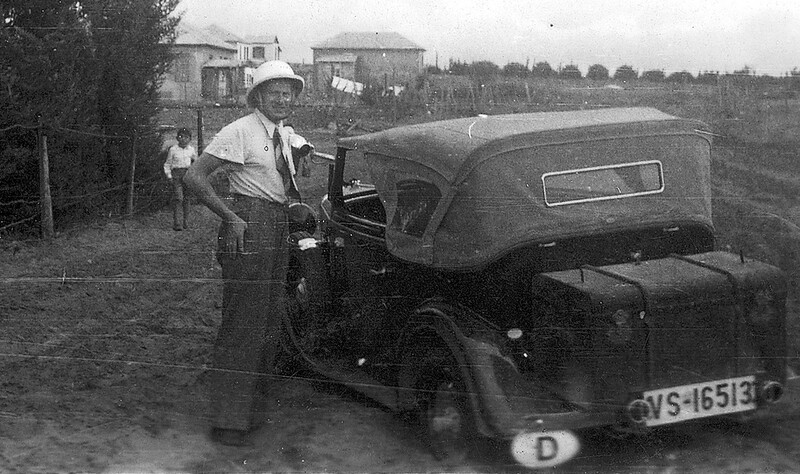

Nazi propagandist Leopold von Mildenstein in Palestine in 1933. (Goldfinger/Tuchler Family Archive/A Sundance Selects release)

This trip was no mere tourist holiday but instead a mission, led by the Tuchlers, for enabling von Mildenstein to write convincing articles for Der Angriff in support of Jewish emigration to Palestine. Although never specified or discussed in The Flat, the Nazi government had in fact been approached about this matter by the Zionist Federation of Germany, of which Kurt Tuchler was an active member, and which argued — in eerie similarity to Nazi racialist views — that Jews, understood as a people separate and apart, were unsuited to reside anywhere but in a country of their own (Lenni Brenner, Zionism in the Age of the Dictators, 1983, chapter 5).

This discovery leads Goldfinger on a search for information that might help explain the relationship described in the articles. Interviewing family members as well as various and sundry Israeli researchers, he confirms the articles’ veracity and learns of the friendship’s post-war continuation.

Yet this attempt at explanation is so heavily enmeshed in the personal-familial, and so wholly divorced from the historical context, that it ends up ignoring the fact that von Mildenstein’s diplomatic relationship with Tuchler, and the sympathies he shared with fellow Nazis for the Zionist cause, have in fact been well-documented in several credible books. One would think research-obsessed Goldfinger, who painstakingly ascertains the murder of his maternal great-grandmother in Theresienstadt, should at least have been aware of this historical research.

Likewise unmentioned are the numerous extant, not unrelated analyses of sordid connections known to have existed between the Zionist effort, the post-Holocaust State of Israel and Germany before and after the Second World War.

Disingenuous

The Flat thus recalls the similarly disingenuous films of Israeli documentary-maker Yulie Cohen Gerstel, who through savvy investigation unearths “obscure” books confirming the Nakba (the ethnic cleansing of Palestine leading to Israel’s establishment in 1948) her aging mother admits having helped perpetrate. Her discoveries are presented as though the current preponderance of solid histories on the subject were nonexistent.

Goldfinger’s approach in The Flat is of a willfully curious yet naive son, confused and angry not only that his mother apparently knew nothing about her embarrassing familial history, but that she has no further interest in it whatsoever.

Goldfinger’s consternation is palpable when Hannah is not “moved” by the fact that von Mildenstein’s daughter, Edda Milz von Mildenstein (who they track down and visit at her home in Wuppertal, Germany, and who herself repeatedly denies her own father’s Nazi past), is not overly disconcerted to learn the awful truth about him.

Indeed the film’s overriding objective, underscored by repeated close-ups on Goldfinger scrutinizing his mother’s ambivalent reactions to ensuing discoveries, is to interrogate “second generation” repression of familial guilt and the disavowal of history.

Such a critical goal is potentially worthwhile — except when pursued, as in this case, at the expense of recognizing and acknowledging Israel’s sordid past and its culpable persistence. The Flat fails to mention the fact of the historical and ongoing ethnic cleansing of Palestine, in which the Tuchlers and the von Mildensteins, who actively supported the very Jewish emigration to Palestine that would lead to the displacement and dispossession of the Palestinian people, are indubitably implicated.

Reinstating taboos

Gerda and Kurt Tuchler (Goldfinger/Tuchler Family Archive/A Sundance Selects release)

Like most Israeli films concerning the Holocaust, and not unlike Holocaust cinema generally, The Flat deflects the crimes of the Nakba onto Nazi crimes through a process of internalization and displacement.

Goldfinger’s abiding guilt over his grandparents’ questionable association with Nazis is assuaged rather than confronted, through a moralizing tack. Edda’s denial of her father’s membership in the SS and his key position within Joseph Goebbels’ propaganda ministry comes off as comparatively worse than anything the Tuchlers or their progeny might have done, regardless of Goldfinger’s inability — and unwillingness — to get to the bottom of that matter.

In effect, The Flat, which appropriately concludes in a cemetery, at once breaks and reinstates the ultimate Zionist taboo of drawing analogies between Israel and Germany and, by extension, between the Nakba and the Holocaust. Concealing such connections by purporting to grapple with an unspoken Israeli past — while pervasively ignoring its most crucial, Palestinian, question — The Flat travesties its ostensible mission of recollection.

As such the film must itself be relegated — ironically, in view of its subject — to the status of propaganda.

Terri Ginsberg is author of Holocaust Film: The Political Aesthetics of Ideology (2007), co-author of Historical Dictionary of Middle Eastern Cinema (2010), and co-editor of A Companion to German Cinema (2012).

Comments

Nazi-Zionist Links

Permalink tony greenstein replied on

I haven't seen the film but I'm sure that Terry's description of it skirting around the issue of the true record of Zionism during the holocaust is true.

One doesn't have to even read Lennin Brenner's books. Ben Hecht's Perfidy (he was a revisionist) concerning the Kastner trial in Israel tells us all we need to know about what happened in Hungary. When this was written up as a play in Jim Allen's Perdition, all hell broke loose but the ZIonists couldn't deny the truth of what happened - a train of 'prominents' out of Hungary for the Zionist and Jewish elite (1684 persons) in exchange for silence and even worse, help, in rounding up nearly 1/2 million Jews for Auschwitz.

Anyone wanting to get an idea of how the Zionist movement prioritised building a State as opposed to saving Jews from extermination could do worse than read the official biographer of Ben Gurion, Shabtai Teveth's 'The Burning Ground' and the chapter on the holocaust.

Or they could also read Hannah Arendt's 'Eichmann in Jerusalem' which the Zionists also heavily attacked at the time (1962).

The Nazi/Zionist connection

Permalink Truth seek replied on

The irrefutable documentation of Zionist collaboration with the Nazis during the 1930's is presented with clarity in The Hidden History by Ralph Schoenman, a Holocaust survivor. The Israeli government refuses to acknowledge or display the commemorative gold coin, with the Nazi swastika on one side and the Star of David on the other side, which was issued to celebrate the trade terms specified in what became known as The Ankara Document. Small wonder, since the coin is a smoldering reminder of their close relationship, in the face of the impending catastrophe.

Books concerning Zionist relation to the Holocaust?

Permalink Sam replied on

Can anyone please lead me to a book which shows, through facts, names and other proof, the zionist connection to the Holocaust and Communist Russia?

http://www.amazon.com/51

Permalink sumood replied on

http://www.amazon.com/51-Docum...

1933 - the great Zionist Appeasement of the Nazis

Permalink Stanley Heller replied on

I wrote about the period here

http://www.thestruggle.org/cou...

talking about 1933 when a spontaneous and then organized anti-Nazi boycott started in many countries and was sabotaged by the Zionists. Von Mildenstein wasn't the only Nazi the Zionists brought to Palestine. See:

http://www.thestruggle.org/SS_...