The Electronic Intifada 28 March 2012

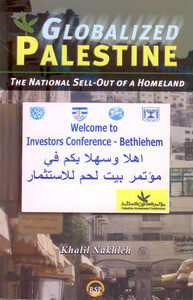

Globalized Palestine: The National Sell-Out of a Homeland explores the rise of a new Palestinian elite that works together with international organizations against the will of the majority of its compatriots.

The book’s author, Khalil Nakhleh, worked in the development sector as director of the Welfare Association (a Palestinian organization) for more than a decade, as well as a consultant on the expenditure of European Union aid. He witnessed first-hand the marriage of the business class and the international aid organizations in Palestine.

Thus, the book is a participant’s observation of how the coalition of Palestinian capitalists (the political and economic elite which benefited from the Oslo accords), the newly-emerging Palestinian nongovernmental organizations and the transnational aid agencies work together — while under occupation — for the myth of “economic development.”

Nakhleh suggests that this coalition is not consciously pre-planned, but that “the longer the current status quo — which is built on the internalized and marketed premise that there is no contradiction between being under occupation and economic development — is accepted and internalized, the more the tripartite coalition becomes purposeful and intentional”(xxi).

Class and capitalism after Oslo

Nakhleh dedicates the two longest chapters in the book to describe the formation of the Palestinian capitalist class.

In chapter two, the author argues that the capitalist class in Palestine is divided into two distinct branches: the expatriates who left historical Palestine, made their money in the shatat (diaspora) — mainly in the Gulf states — and came back after Oslo in the mid-1990s; and the indigenous capitalist class, formed of small family businesses which depend on subcontracting to Israeli businesses.

Nakhleh argues that the Palestinian Authority has always been biased toward the shatat capitalists due to their “control of huge capital accumulation and their direct interplay with the PLO [Palestine Liberation Organization] as supporters of its agenda” (66).

The history of this union of shatat capitalists and the PA elites is exemplified by the rise of two particular capitalists — Abdul Majeed Shoman of the Arab Bank, and Hasib Sabbagh of the Contractor Construction Company — and the role they played as mediators between the PLO, the Arab regimes and the US. For example, the two helped mediate a way out of the PLO from Jordan after “Black September” in 1970 (King Hussein’s brutal crackdown on the PLO).

The second example of expatriate relations with the PLO before Oslo is provided through the Palestinian capitalist class in Egypt. This is illustrated by the case of Sami al-Shawa, who amassed a fortune in the pipes industry, and others from the Gaza Strip who studied in Israel and transferred their skills to start businesses in Egypt. This class played a role in normalizing economic relations with Israel.

Favoring monopolies

The marriage of capitalists and PA elites was renewed and solidified with the return of those from exile during the formation of the PA as a result of the Oslo accords. By designing of laws that favored monopolies in real estate and banking, the PA enabled the shatat capitalists to profit from new investments, marginalizing smaller family businesses.

The shatat elites, who occupied positions in policy-making centers, worked to ensure regulatory structures and general economic policies such as monopolies, foreign investments, reduction of taxes and the favoring of certain sectors to keep their interests in having total control over the PA’s economic activities.

Consolidation of the neoliberal order would not have been possible without the role played by the nongovernmental organizations. Through a process of employing the middle classes and the educated Palestinians in the NGOs, the shatat capitalists whose organizations — such as the Welfare Association — played a mediator role between the international donors and the Palestinians who worked on the de-politicization of the Palestinian society and therefore the normalization of occupation.

Altruism and nationalist rhetoric

The altruism of the shatat capitalists is not only reflected through their charity organizations, but also through their rhetoric of nationalism: their return to Palestine with the PA is sheer altruism driven by their love for Palestine and their willingness to build the nation.

Hence the hegemony of the shatat capitalists is consolidated through their control of the economic activities, and their influence in the political arena — and at the same time, their administration of the civil society sector is represented by the NGOs. This hegemonic presence has stifled the imagination of the Palestinians and domesticated them to accept the status quo in a locked system that seems hard to break.

The solutions offered by the author, under the headline of People-Centered Liberation Development, however, reads like a shopping list from the World Bank, which contradicts Nakhleh’s own analysis. Despite the author’s analysis of the tripartite coalition and its hegemony, he proposes a focus on community development and small-scale enterprises. Many questions can be posed here — the most important of which is how can the focus on the community, on education and skills fight a tripartite coalition of political and economic elites, international organizations and the development NGOs?

Perhaps twenty years of work in the development sector makes it hard for the author to imagine another paradigm of development. Perhaps it is the power of the neoliberal ideology that has stifled his and our imagination to envision solutions beyond those proferred by the same power structure criticized in the book.

The book’s analysis is also undermined by the author’s moral tone. Despite his acute analysis of the system that created these class structures and the entanglement of their interests with the global elites, the author offers solutions not according to their interests but to certain values they should hold as Palestinians: they sell out their homeland and become normalizers with the occupation when they do not abide by these values.

Moreover, the author jumps to conclusions at points without backing up his claims. This undermines the message of the book. However, Globalized Palestine is still valuable to all those interested in understanding the socio-economic situation in the West Bank, as well as those who are interested in working for justice in all of Palestine.

Mayssun Sukarieh is an independent researcher.