The Electronic Intifada 16 August 2004

The issue of Palestinian development has been in the limelight for sometime now. For over a decade, billions of taxpayer dollars from countries around the globe have been flooding into one of the smallest yet-to-be countries, the Palestinian Authority (PA). In year 2004, the Palestinian people have become the largest per capita recipient of foreign aid in the world. Yet, Palestine is not only unable to move forward in its development process toward statehood, but rather, any achievements that have been made thus far are being unraveled while donor funds continue to flow unabated. As Dr. Khalil Nakhleh illustrates in The Myth of Palestinian Development, this process of “de-developing” Palestine is not haphazard or a strike of bad fate, but rather an externally planned systematic approach to the Palestinian reality that Palestinians must reverse.

The issue of Palestinian development has been in the limelight for sometime now. For over a decade, billions of taxpayer dollars from countries around the globe have been flooding into one of the smallest yet-to-be countries, the Palestinian Authority (PA). In year 2004, the Palestinian people have become the largest per capita recipient of foreign aid in the world. Yet, Palestine is not only unable to move forward in its development process toward statehood, but rather, any achievements that have been made thus far are being unraveled while donor funds continue to flow unabated. As Dr. Khalil Nakhleh illustrates in The Myth of Palestinian Development, this process of “de-developing” Palestine is not haphazard or a strike of bad fate, but rather an externally planned systematic approach to the Palestinian reality that Palestinians must reverse.

The Myth of Palestinian Development, as stated by the author, “is not an attempt to find a ‘magi-cal’ recipe for how things should be done in order to ensure the ‘desired’ development of Palestinian society.” Dr. Nakhleh rightly believes that, “no such thing [‘magi-cal’ recipe] is possible. Anyone who claims the contrary is, in the best situation, unaware and unappreciative of the complexities of the ‘development’ process, and, in the worst, part of a premeditated process of deceit generated by a chorus of development ‘agents provocateurs’ to maximize self-benefits.”

From the book’s subtitle, which is “Political Aid and Sustainable Deceit,” and throughout, the reader is forced to think deeper than the superficial headlines of today’s media coverage of Palestine. Dr. Nakhleh puts the context of the Palestinian struggle for freedom and independence into today’s world of “globalization and trans-nationalization,” something few Palestinian analysts address. He states, “If the function of the nation-state is being redefined in the context of globalization, then the entire concept of national sovereignty and national interests needs rethinking.” Taking such a step back from the day-to-day atrocities in Palestine is crucial if Palestinians are to be able to position themselves in a way to actually realize the fruits of their struggle.

Soberly linking today’s world dynamics with current Palestinian development toward statehood, Dr. Nakhleh states: “Stability in the region, the creation of conducive conditions for globalized production, and the mobility of transnational capital are the primary objectives and concern of the interventions, not genuine Palestinian development.”

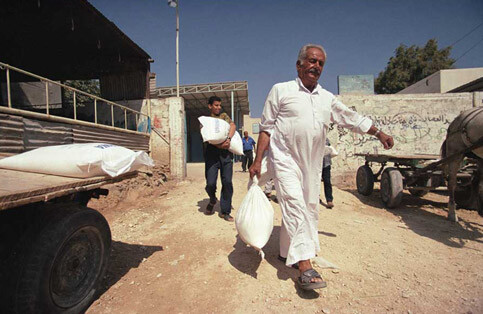

Palestinians carry UNRWA bags at a food distribution point in Gaza. (Ronald de Hommel)

After a critical reading of the book and internalizing it with my own personal experience in the Palestinian struggle during the period being covered, 1984 - 2001, I can attest that Dr. Nakhleh spectacularly reveals the inner workings of an entire donor industry that has been built around the catastrophic predicament of the Palestinian people — an industry that is sustained by the so-called ‘peace process’ and previously by the so-called ‘revolution.’

The Myth of Palestinian Development is a focused biography that takes a deep and serious look into how two funding agencies, in particular, and the entire donor community in general, including pre-Oslo Palestinian and Arab donors, view and act toward Palestinian development. The book takes a unique approach by surveying the Palestinian de-development process through his own work experience with the two most significant developmental agencies of the pre and post-Oslo periods, The Welfare Association (1984-1992) and the European Commission (1993-2001).

The Welfare Association, a Swiss-registered non-profit organization, established in 1983, was the first serious attempt by a few wealthy Palestinians to foster Palestinian development. Dr. Nakhleh takes the reader through the maze of the fund’s alliances — largely governmental linked — and provides samples of various interventions and how those interventions were diverted from developmental-based to emergency-based during the first intifada.

Dr. Nakhleh believes that the Palestinian capitalists’ “tendency to push towards becoming more ‘mainstream responsive’ and much less ‘developmental,’” put the real work of developing Palestine based on future needs in total disarray. The author gives a sample of development under Israeli occupation during the 1980s and describes the complexities of financially supporting Palestinians during the first intifada while the Israeli military was fully tracking where interventions were being made and by whom. Currently living in the occupied territories myself, I feel that remembering the lessons of the 1980s now is a timely lesson since Palestine seems to be heading into another era of clandestine development in the face of recrudescent oppression.

Reviewing how the first Gulf War shook the region and in particular the Palestinian mode of operation, Dr. Nakhleh boldly addresses the Welfare Association’s board -some of the wealthiest Palestinians in the world - as utilizing their ‘privileged communications channels’ to veer the development process from an institutional and need-based intervention to a personalized, nepotistic approach that favored appeasing the powers-to-be. This step away from professional management made the Association loose its core potential to affect its declared goals of true national development.

During the post-Oslo period, a flurry of donor pledges, commitments, and disbursements (three very different items, as described in this book) were made by the world community who took upon themselves to intervene on behalf of Palestinian development. Again, through Dr. Nakhleh’s firsthand experience with the largest donor to Palestine, the European Union (EU), he describes in detail how this aid flow failed to foster development, and in reality contributed to de-developing Palestine.

As stated by the EU, the “political input and economic contribution has been the determining element for the survival of the Palestinian Authority,” Dr. Nakhleh asks, “Is it, for example, the type of ‘survival’ that the EC [European Commission] aid offers that hooks entire PA institutions to a ‘life sustaining machine,’ which manages to inject intravenously small, yet steady doses of cash to keep the entire public sector afloat?”

Dr. Nakhleh provides noteworthy insight into the people through which the development funds were channeled; he calls them the “New Mercenaries.” “The New Mercenaries are a rapidly emerging category of global professional hustlers, who compete via the international media to sell their ‘expertise’ and ‘experience’ to the highest bidder…They roam about unhindered by national boundaries or limitations…The New Mercenaries are the ‘nomads’ of globalized economies and societies, and the ubiquitous hallmark of development projects. They are transient; only a few of them experience the repetition of seasons in the same place. Thus, they rarely see the results of their work.” Anyone visiting Palestine these days will find these international consultants — “New Mercenaries” - in every aspect of Palestinian life — politics, security, economy, education, etc. - all holding VIP cards and freely passing through Israeli military checkpoints with 4x4 sport utility vehicles in one of the most deprived and unfree places in the world. It is unfortunate that the Palestinians alone are being held responsible for their statehood building misgivings, when in reality, donor money and donor-picked consultants are really in the ‘developmental’ driving seat.

Dr. Nakhleh’s does not only characterize the problem, but offers ideas for how to move ahead. He notes, “I want to examine whether the genuine development for which we - at least I am - aspiring, is at all feasible in a non-sovereign context.” This issue of sovereignty is in the forefront of today’s debate. As stated in the book, “ ‘Autonomy’ began to be perceived by the newly constituted PA as tantamount to ‘sovereignty.’” As the author accurately notes, “The degree of whatever sovereignty it [the PA] possessed was determined, de facto, by Israel, and not by the Accords it had signed.”

“Not once, through the stretch of the last hundred years, were the Palestinians in a real and effective position to decide on the context of intervention in Palestine.” He also adds: “The two times when they had the potential of insisting on the inclusion of positive societal developmental ingredients, during the second half of the 1980’s and the mid-1990s, they failed to do so at all levels: that of the ‘leadership,’ the community-based organizations, and the ‘nationalist capital.’” The challenge ahead for Palestinians is huge indeed and Dr. Nakhleh does not shy away from starting to address it.

The two agencies under review are analyzed by the historical origins of each of their involvements in Palestine, the strategy of intervention they adopted, a review of each agencies record of intervention, the agencies decision structure, and the writer’s assessment. The actual records of interventions are supported with excerpts from the author’s field notes and reports at the time, an invaluable window into history.

One full chapter is dedicated to a comparison of twelve basic developmental variables (pre and post-Oslo periods) along with the author’s candid opinion of each agencies role in the development process. The 17 years discussed in the analysis cover the historical period that has defined today’s struggle for Palestinian independence.

The final chapter is where Dr. Nakhleh puts the bulk of his critical assessment and proposes what needs to be done. Presenting the topic as a researcher, a practitioner and a Palestinian citizen under occupation, one comes away with an array of issues as food for thought, or as Dr. Nakhleh would agree, food for action.

Specific steps are noted to “ ‘indigenize’ the objectives” of Palestinian development. Some are rather specific steps, such as the elimination of the Economic Council for Development and Reconstruction (PECDAR), the agency that the donor countries created prior to Palestinian ministries and bureaucracy being set up. Dr. Nakhleh terms this agency as, “the vestige of the World Bank and the externally imposed agendas.”

Dr. Nakhleh calls for “societal participation” in the developmental planning process of Palestine. A difficult task for sure, but one Dr. Nakhleh says “cannot be attained by simply embellishing the existing structure.” He asserts that “the requirements must be internal, structural and systematic; they must be transformational, and relate directly to the Palestinian system of governance.”

In summary, Dr. Nakhleh coins what needs to be done as “indigenous empowerment” and the target of empowerment squarely being “the ordinary Palestinian person.”

Having read The Myth of Palestinian Development immediately after reading Prof. Francis A. Boyle’s new book Palestine, Palestinians and International Law (Clarity, 2003), which reveals another set of continuous strategic faults of the Palestinian leadership through the eyes of a practitioner, like Dr. Nakhleh, who was dealing in the realm of international law, working with the ‘trees’ while still being able to see the ‘forest’. Both books are absolutely crucial to the broader understanding of why the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is where it is today. The incompetency and disregard toward Palestinian planning, particularly in the legal and developmental aspects, bring one to the bold conclusion that serious internal restructuring is required within the Palestinian liberation movement before any real progress will be realized in ending the illegal Israeli occupation and establishing the State of Palestine.

Sam Bahour, a Palestinian-American, lives in the besieged Palestinian City of Al-Bireh and is co-author of HOMELAND: Oral Histories of Palestine and Palestinians (1994) and can be reached at sbahour@palnet.com.

Related Links