Electronic Lebanon 27 August 2009

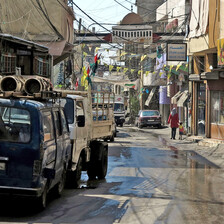

Destroyed homes around Nahr al-Bared remain sealed off. (a-films)

NAHR AL-BARED, Lebanon (IPS) - Palestinian refugees at Nahr al-Bared in north Lebanon are living under tight military siege two years after a war destroyed the refugee camp. It has now become a test case for a new approach in Lebanon’s security policy towards Palestinian refugee camps.

The 200,000 square meters camp is located on the Mediterranean coast, about 16 kilometers north of Tripoli. Adjacent to the highway leading from Beirut to the Syrian border, Nahr al-Bared is surrounded by the villages of Akkar, a neglected region dominated by Sunni Muslims and Maronite Christians.

A fierce battle between the militant group Fatah al-Islam and the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) raged in the camp from May to September 2007. The 15 weeks of fighting left more than 400 persons dead, among them 170 soldiers and 54 civilians, while the core of Nahr al-Bared was completely destroyed, and the adjacent area partly ruined.

Since October 2007, more than half of Nahr al-Bared’s 30,000 residents have returned to the camp’s outskirts. Mostly living in makeshift dwellings and in the ruins of their homes, the refugees are waiting for the camp to be rebuilt. After several delays, reconstruction work finally started at the end of June 2009.

The Lebanese army entered a Palestinian refugee camp in 2007 for the first time since the end of the 1975-1990 civil war, which was fought largely between Christian and Islamic groups. After the end of fighting at the camp in September 2007, the LAF have gradually handed over neighborhoods in the adjacent area to former residents, withdrawing their forces to the core of the camp. But several military checkpoints are in place at entrances. Barbed wire and concrete walls seal it off from its environs.

Lebanon hosts an estimated 200,000-250,000 Palestinian refugees. About half live at the 12 official camps. But unlike other Palestinian refugee camps in Baalbek, Beirut, Saida and Tyre, the two camps in north Lebanon — Beddawi and Nahr al-Bared — were not routinely encircled by military barricades earlier, and their residents enjoyed considerable freedom of movement, developing good relations with neighboring Lebanese villagers.

Residents of Nahr al-Bared and Beddawi were allowed to bring in building materials, while restrictions still apply at the camps in the south, even if they have been slightly eased over the last few years.

Entry restrictions were introduced at Nahr al-Bared a few months before the fighting broke out. The LAF controls access to the camp by a strict permit system. Acquiring permits can take weeks, and they are often refused. Journalists, and employees of international non-governmental and human rights organizations were barred, and can still face difficulty obtaining permits.

“Look, every one of us has an identity card that is accepted everywhere,” says Imam Sheikh Ismail at the al-Quds mosque at the camp, pulling out his identity card. “Why do we need an additional permit? It’s the same information on both papers, exactly the same information.”

Othman Badr, journalist and outspoken member of the Residents’ Committee, says the state has a right to place checkpoints where it wants to. But the permits are the main problem, he says. “It’s against all human rights that somebody needs a permit to return home or to invite friends.”

Entry restrictions seriously hamper efforts to revitalize Nahr al-Bared’s once flourishing economy. The camp was open for Lebanese customers attracted by its cheap prices. The camp’s businessmen used to import goods from nearby Syria, selling them with a small profit margin. The camp became a thriving marketplace in Akkar.

Nahr al-Bared had about 1,500 micro, small and medium enterprises, mostly in trade and services, and some small manufacturing units. Since the end of the fighting, refugees have started to open small businesses on the outskirts of the camp.

“The problem is that we have hardly any customers from outside the camp,” says Mohammad Hamed, who has recently set up a small restaurant. “The money people spend here circulates only inside the camp. We have hardly any income.” Hamed has sales of about $35 a day, with a profit margin of about $5 (a meat sandwich sells for less than a dollar). Similar accounts are heard throughout Nahr al-Bared.

Abu Ali Mawed, president of the local traders’ committee, says the siege of the refugee camp is the main obstacle. “The camp is a closed military zone. Our neighbors are not allowed to enter. How should the economy of the camp develop under these circumstances?”

Non-governmental organizations working in Nahr al-Bared protested against the restrictions in a letter in January this year. Residents have voiced their opposition several times. Charlie Higgins, project manager for reconstruction of Nahr al-Bared with the UN agency for Palestine refugees (UNRWA), has demanded a review of army-controlled checkpoints.

But the Lebanese government does not intend to withdraw security forces from Nahr al-Bared once the camp is rebuilt. The camp will be placed under Lebanese sovereignty, meaning that the Internal Security Forces (ISF) will be present inside Nahr al-Bared.

The Lebanese attempt to control the camp is directly connected with the issue of Palestinian arms. Several Palestinian groups maintain a military wing, equipped with guns, grenade launchers and hand grenades. Disarmament is firmly opposed within the camps. Given a history of frequent conflicts, weapons are considered essential for protection of the camps.

“Nahr al-Bared emerged as a test case of whether and how well Lebanon could assume security responsibility in the camps,” the International Crisis Group said in a report in February this year. So far, the total destruction of their camp, the looting and burning of their homes, the violent conduct of Lebanese soldiers at checkpoints, intimidation by military intelligence, restrictions on freedom of movement, and the siege have anything but persuaded the camp’s residents to trust the Lebanese security apparatus.

Nidal Abdelal from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine points to what he considers the real question over reconstruction of Nahr al- Bared. “Will it be a project for the enduring resettlement of the Palestinians in order to abolish their right to return? Under which political circumstances will the camp be rebuilt?” Many Nahr al-Bared refugees say the reconstruction will be a test case for their long-term resettlement in Lebanon. Its foretaste is quite bitter.

Ray Smith works with the autonomous media collective ‘a-films,’ which has documented developments in Nahr al-Bared over the past two years.

All rights reserved, IPS - Inter Press Service (2009). Total or partial publication, retransmission or sale forbidden.