The Electronic Intifada 13 July 2009

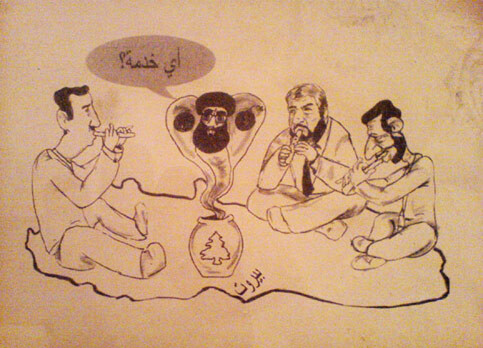

An Israeli leaflet dropped on Lebanon in 2006 depicts Hizballah leader Hassan Nasrallah as a snake being charmed by the Syrian and Iranian presidents, and the Hamas leader Khaled Meshal. (Zena)

On 31 May and 1 June of this year, two articles by culture reporter Daniel J. Wakin appeared on the The New York Times website: “Minuets, Sonatas and Politics in the West Bank,” and “Amid West Bank’s Turmoil, the Pull of Strings.” It is clear before we even begin reading that we are going to be indebted to Wakin for providing us with a romantic filter through which to view an otherwise sobering subject, just as we might be indebted to someone for writing about the athletic pursuits of disabled persons or about clandestine wine tasting groups under the Taliban.

The heroine of the first article is 16-year-old Dalia Moukarker from Beit Jala near Bethlehem, whom Wakin describes as “one of a new generation of Palestinians who have been swept up in a rising tide of interest in Western classical music in the last several years here in the Palestinian territories, but especially the West Bank.” Wakin does not explain why Gaza has been behind the “rising tide,” although it may have something to do with the ban on importing musical instruments.

Three years of flute study have enabled Dalia to “dispatch … the courtly melodies and cascading runs of an 18th-century concerto with surprising self-assurance,” adding to “[t]he sounds of trills and arpeggios, Bach minuets and Beethoven sonatas [that] are rising up amid the economic malaise and restrictions of the Israeli occupation.” The bittersweet landscape is augmented with images of Dalia “sometimes retreating to a bathroom in her crowded apartment [to practice], sometimes skipping meals.” Wakin confirms that, “As with many endeavors in this part of the world, the pursuit of classical music is fraught with tensions and obstacles,” and goes on to explore one example:

“A small effort to teach violin at a refugee camp in Jenin, north of Ramallah, was banned in March when camp authorities heard that the students had played for Holocaust survivors in Israel, saying the concert ‘served enemy interests.’ A lack of detailed knowledge about the Holocaust is widespread among Palestinians, who view that chapter of history as a catalyst to the creation of Israel and thus a source of their suffering. But the music teacher, Wafaa Younis, an Israeli Arab, scoffed at the complaint. ‘I don’t think it should be a problem,’ she said.”

Thus, just as it is apparently impossible for the President of the United States to visit the Middle East without a corresponding visit to Buchenwald, it is apparently also impossible to have a news article on Palestinian humanity without a corresponding reminder that Arabs do not understand the Holocaust. A more relevant lack of understanding in the context of Jenin might involve the Israeli refusal to understand that entire villages cannot be bulldozed. The use of music as a political tool is meanwhile noted by Wakin himself in a 2008 The New York Times article entitled “North Koreans Welcome Symphonic Diplomacy,” in which the New York philharmonic makes an audience in Pyongyang cry but in the end does not have any detectable effect on North Korean nuclear intentions.

After music teacher Wafaa Younis has reassured readers that playing for Holocaust survivors is not a problem, Wakin returns to the question of unawareness, this time admitting that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is one in which “mutual ignorance is prodigious.” It turns out, however, that the Israeli half of mutual ignorance merely consists of a lack of appreciation for Palestinian musical ambitions. Wakin quotes a music critic for the liberal Israeli daily Haaretz as declaring that “[w]e cannot perceive [Palestinians] as people who have their own cultural lives,” although we are not informed of what the cultural assessments of a non-liberal daily might be.

Liberal criticism in this case coincides with the line of thinking of Princeton University historian Bernard Lewis, whose suggestions for “what went wrong” with Islamic civilization include second-rate musical traditions stemming from a general Muslim disdain for timekeeping. Flexible conceptions of time preclude the pursuit of Western musical standards like polyphony, which according to Lewis helps to explain why the West is naturally compatible with democracy and other harmonious collaborations between various performers and the Islamic world is not.

Lewis’ premise is challenged by leaflets dropped on Lebanon by the Israeli air force in 2006, some of which feature Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, Hamas leader Khaled Meshal, and Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad playing flutes in a blatant instance of multi-performer collaboration among Muslims. Via its flute-playing, the ensemble is summoning Hizballah leader Hassan Nasrallah — in the form of a snake-genie — out of a small vessel positioned in the center of the group and marked with a Lebanese flag. Whether or not the three musicians are keeping accurate time is of course another matter, as even the late Edward Said had once remarked that Nasrallah was the only punctual Middle Eastern leader he had encountered.

Further experiments in polyphony can be identified in the Barenboim-Said Foundation, a collaboration between Edward Said and Israeli musician Daniel Barenboim, which Wakin describes as “[o]ne of the major players in the nurturing of classical music” in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Dalia of Beit Jala hopes to receive a scholarship from the Foundation to study music in France.

Polyphonic success is tempered with Wakin’s subsequent description of the falling out between the Barenboim-Said Foundation and the Edward Said National Conservatory of Music due to complaints by the conservatory’s director that Barenboim was “effectively supporting the Israeli occupation by not using the orchestra to oppose Israeli policies.” The director is quoted as follows: “The fact on the ground is that Israel occupies Palestine … If one guy’s foot is on the neck of another, you can’t sing together.”

It is probably even more difficult to sing if the guy with the foot on his neck then has one foot in terror and the other in politics, an arrangement Hamas and Hizballah were repeatedly warned about by former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. Wakin nonetheless suggests that Islam and classical music can coexist, and ends his article at a West Bank concert by a visiting European musician, where “[t]he call to prayer from a nearby mosque mingled with the notes coming from his gleaming golden flute.” He of course failed to specify whether the mingling was polyphonic.

At one point in the article Dalia explains that the flute “takes me to another world that is far away from here, a more beautiful world.” The aesthetic flaws of her current world may be due in part to the fact that she enjoys a view of the Israeli separation fence from her bedroom window; Wakin meanwhile continues the bittersweet reduction of Palestinian tragedy in his second article, “Amid West Bank’s Turmoil, the Pull of Strings,” the hero of which is 18-year-old Shehade Shelaldeh of Ramallah.

Shehade is introduced as, “The young man was handy with tools. A carpenter’s nephew, he liked to fix chairs, windows and door locks. At other times he would stand idly on the street corner.” Enter French-trained violist Ramzi Aburedwan, founder of Ramallah’s al-Kamandjati music center, who takes advantage of Shehade’s idle periods to turn him into a violin repairman. Aburedwan, reports Wakin, had been photographed throwing a rock at Israeli soldiers during the first intifada but then effectively traded in his rock for a viola. Shehade’s political progression is charted by the presence of “a small Palestinian flag decal on the base” of the first violin he made.

Aburedwan asserts that he “want[s] these kids to participate in the building of a Palestinian cultural future,” which Wakin acknowledges might be useful “at a moment when the prospects for a Palestinian state seem to be receding.” As Wakin’s two articles preceded Barack Obama’s speech to the Muslim world in Cairo by several days, the question is then raised of why Obama still felt the need to express US support for Palestinian national ambitions. The primary requirement for peace as laid out in the speech — “Palestinians must abandon violence” — is, however, compatible with the rock-for-instrument model.

Obama’s itemization in Cairo of anti-Jewish moments in history included not only the gas chambers of World War II but also sleeping Israeli children on the receiving end of rockets and old women being blown up on buses. Palestinians, on the other hand, are denied any sort of parallel individuality and are merely established as the formless victims of a formless humanitarian crisis in Gaza, the most crucial aspect of which is that it “does not serve Israel’s security.” Wakin’s first piece offers increased victimhood to the inhabitants of Gaza, which he admits was recently “pummeled by a 22-day war,” but he still refrains from counting casualties, opting instead to tally Israeli victims of suicide bombings as a justification for the separation fence.

As for the identity afforded Dalia and Shehade, it seems at times that they are being confined to romanticized roles such that we might in turn empathize with the Palestinian experience within a similarly confined space. (The only thing lacking is a third article in which the young loiterer-turned-luthier with gelled hair becomes enamored of the maiden playing her flute in the bathroom). Wakin focuses empathy through strategic gems such as the following: “In a place all too familiar with the sounds of gunfire, military vehicles and explosions, [Shehade] said, ‘Al Kamandjati taught us to hear music.’” The article concludes with Shehade’s describing his dream “to become a famous instrument repairer.” It would of course possess less of a romantic air if Shehade’s dream was instead to become a famous house repairer in Jenin.

Belén Fernández’ book Coffee with Hezbollah is due for publication in the coming months. She is a contributing editor at pulsemedia.org, and her articles have appeared in CounterPunch, Palestine Chronicle, and Venezuelanalysis.com