The Electronic Intifada 15 October 2024

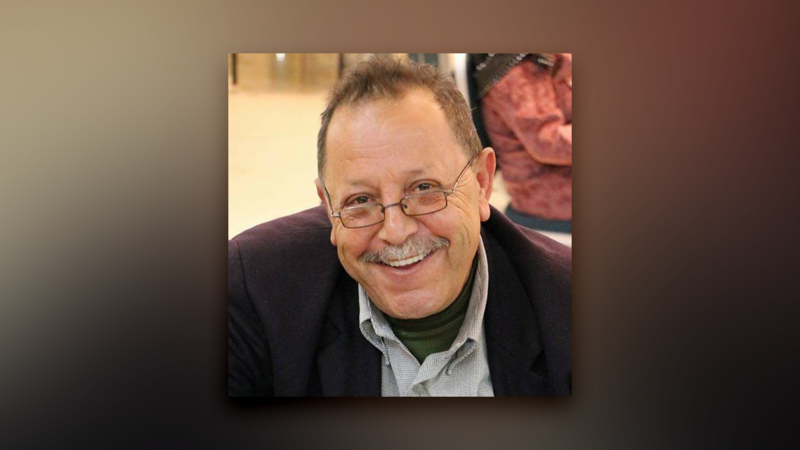

Muhammad Abdel Malik al-Sheikh.

The news of the killing of Muhammad Abdel Malik al-Sheikh and his family hit me like a bolt from the blue.

Abu al-Abd, as I always knew him, was my companion and partner on a journey we took together for more than 18 years.

Although distance separated us in recent times, this final farewell has been the hardest thing to bear.

How can I describe the pain of losing him, feeling helpless and far away?

The message hit me like lightning: “Abu al-Abd al-Sheikh, his wife, Mahaasin, and his son, Abdelaziz, have been martyred. Pray for their souls.”

We had spoken just a week before he was killed

Abu al-Abd and I had worked together on projects that changed the lives of many women in our community. Together, we ran a now-closed vegetable freezing plant factory to employ women in Beit Lahia.

His intelligence and innovative solutions were the key to success. He was the only man among more than 80 women, and his brilliant mind saw opportunities where others saw obstacles.

We didn’t have enough resources to buy equipment, so we built what we needed ourselves with the help of blacksmiths. We designed ovens and milk pasteurization machines, and we improvised solutions when the electricity went out, such as using wood as an energy substitute.

Even when it came to the smallest items or details – there was, for instance, a shortage of glass jars at one point – we didn’t hesitate to go to Rafah shere smuggling tunnels could get us such things.

Thanks to Abu al-Abd’s efforts, we successfully implemented 140 small projects to support disadvantaged women and families, ensuring that each of the families received grants of $5,000 — funded by the Islamic Bank.

Our vision was to empower each family to break free from the cycle of poverty.

Dealing with loss

Now, I am asking myself: How can I mourn Abu al-Abd?

How can I grasp that he is no longer here when he was such an integral part of my life?

In times of war and exile, we too often experience the loss of loved ones from afar. We can only follow their news through screens or receive brief messages that fail to ease the pain.

At the start of the Israeli genocide, fleeing was not an option for Abu al-Abd. Even though the shelling surrounded him on all sides, he refused to move south, remaining optimistic that the war would not last long.

Abu al-Abd and I spoke in late September about the pain he was experiencing due to a slipped disc and how walking had become a challenge for him even with a cane.

One night he had planned to seek shelter at an UNRWA facility in the very north, but at the last minute changed his mind. It was a good decision. A massive explosion struck close to the facility just after he had turned around.

Despite the injury, he said: “We were running, and I didn’t feel the back pain because life is precious.”

Abu al-Abd also told me about going to the small apartment he kept for a son in Jabalia. This simple decision seemingly saved him from a massive explosion that occurred after he left his home in the al-Daraj neighborhood east of Gaza City, whose force swept away everything in its path.

I felt that God was protecting him. Yet, despite surviving, he was exhausted and, like many people in Gaza, tired of displacement and uprooting. Still he decided to return to his damaged home to fix what could be fixed.

“We’ll stay close to our home, Um Abdullah,” he told me.

Our conversations helped me understand the meaning of living in fear and clinging to hope despite the shelling and destruction. Abu al-Abd insisted on staying in his home despite the surrounding devastation, believing that life must go on and that displacement does not mean safety.

I told him that I loved him and appreciated him. I was lucky to have been able to share my feelings and express what he meant to me. Many in exile never get that chance. They live through the tragedy of losing their loved ones without the opportunity to bid them farewell or tell them how much they meant in their lives.

Family life and loss

Amid all the hardships, I shared what little money I had with Abu al-Abd, keeping the rest for my family.

Abu Al-Abd was not reckless or suicidal. He did not return to a dangerous area on the frontlines, but rather went to his home in the al-Daraj neighborhood where many residents either remained in their homes or took refuge in nearby schools after their homes were bombed.

In one of our conversation, Abu al-Abd said he feared that I might collapse under the stress of what people in Gaza are going through.

Now he’s the one who’s gone, leaving me suddenly alone.

How can I face this loss?

How do I cope with his absence?

Abu al-Abd meant everything to me, and now that’s all I think about.

Both of us were blessed with one child, and I shared with him the experience of IVF, which was a miracle in my life.

Abu al-Abd raised his son in an exemplary way. Abdelaziz, 18, was a hafiz – one who has memorized the Quran – and a medical student. My little one still struggles with autism. I pray to God that I can raise my child as well as Abu al-Abd raised his son.

Abu al-Abd passed as a martyr, along with Mahaasin, a kind woman who was always smiling, thankful and content.

She had faced breast cancer with an unbreakable will. She triumphed over the disease thanks to her strong determination and love for life. Even after losing her long black hair and undergoing a mastectomy, her spirit was not broken.

On the contrary, she became even stronger and more determined to see her son grow up and get married, fulfilling their dreams as a family.

The Sheikh family lived with hope, always looking forward to a better tomorrow. The occupation didn’t even allow them that dream. Israeli weapons blew up a wall that had survived a previous attack, sentencing the family to death while they were asleep.

No mercy. No humanity.

May God have mercy on you, Abu al-Abd, your wife, and your son. You passed as martyrs, leaving behind a legacy of love and giving.

Nawal Soleman Akel is a student of political science living in Belgium.