Beirut 4 August 2006

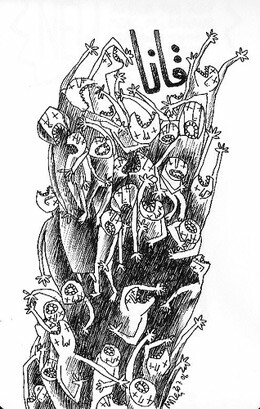

“Qana” by Mazen Kerbaj. View more of his work.

This week “justice” came to the Lebanese Village of Qana. The United States had blocked every attempt to end the violence, and, before the attack, Israeli Justice Minister Haim Ramon had announced that “everyone who is still in south Lebanon is linked to Hizbullah.” The Anglo-American-Israeli juggernaut had brought “justice” to “our enemies.”

Reacting to the horrors of World War II, the bold-thinking Max Horkheimer suggested that we finally make social progress from the experience of the opposite of justice. We learn about the value of the individual life, for instance, from the experience of a world that treads mercilessly on human lives and bodies, treating them as so much soulless stuff. Though a European Jew, Horkheimer was a dialectical materialist, and therefore no kind of theist. Yet he believed that the notion that each human is equally and, in a sense, infinitely valuable, was a religious innovation. “The very concept of the soul as the inner light, the dwelling place of God,” he wrote, “came into being only with Christianity, and all antiquity has an element of emptiness and aloofness by contrast.” To our modern sensibilities, he observed, “some of the Gospel teachings and stories about the simple fishermen and carpenters of Galilee seem to make the Greek masterpieces mute and soulless - lacking that very ‘inner light’ - and the leading figures of antiquity roughhewn and barbaric.” For Horkheimer, this insight came from the painful experience of its negation, and any hope of justice lay, paradoxically, in the deep experience of injustice. Hence, “the anonymous martyrs of the concentration camps are the symbols of the humanity that is striving to be born,” and we could expect insight from those “who have gone through the infernos of suffering and degradation in their resistance to conquest and oppression.”

Hassan Nasrallah speaks to the Arab world and the Muslim World about their common experience of injustice. Do not doubt its deep resonance, its truth. Qana is just the latest, and one of the clearest, and most globally visible, examples. Can those who launched the endless war finally recognize the infinitely valuable “inner light” so callously snuffed out of each of those dusty child corpses? Will Nasrallah, and those now fixated on his voice, see justice, against the background of injustice, any more clearly than did Bush and those fixated on his voice? Can we expect such magnanimity, given the asymmetry of the suffering?

In human affairs, cycles of violence and revenge, cascades of injustice, are not inevitable. Our sole hope is that we have not only an inner light but an ability to choose and act, to consider not only means, but ends, with what Horkheimer called reason - that having lived through hell, we might see not only the injustice done to us, but the horror of injustice no matter who is the victim. A simple thing. We know the alternative.

Related Links

Patrick McGreevy heads up the American Studies Program at the American University of Beirut