The Electronic Intifada 25 April 2011

Raja Khalidi

Earlier this month, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the United Nations Special Coordinator for the Middle East Peace Process (UNSCO) each published reports backing the Palestinian Authority statehood program. They claim that from an institutional point of view, the PA is ready for the establishment of a state in the near future.

In August 2009, the PA published a strategy paper called “Ending the Occupation, Establishing the State.” The Palestinian statehood program states that the establishment of a Palestinian state within two years “is not only possible, it is essential.” The PA stresses the building of “strong state institutions capable of providing for the needs of our citizens, despite the occupation.” As concerns the economic system, “Palestine shall be based on the principles of a free market economy,” the program states.

Recently, Palestinian economists Raja Khalidi and Sobhi Samour published a highly critical article on the PA’s neoliberal policies in the Journal of Palestine Studies entitled “Neoliberalism as Liberation: The Statehood Program and the Remaking of the Palestinian National Movement.” Khalidi and Samour argue that the statehood program “cannot succeed either as a midwife of independence or as a strategy for Palestinian economic development.” They claim that the PA is offering the Palestinians living in the occupied West Bank “a program predicated upon delivering growth and prosperity without any strategy for resistance or challenge to the parameters of occupation.”

The Electronic Intifada contributor Ray Smith interviewed Raja Khalidi, a senior economist with the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), about the PA’s economic policies and its implications for statehood. The views expressed in this interview do not represent those of the UN secretariat.

Ray Smith: How do you feel about the unanimous praise from those leading international institutions?

Raja Khalidi: Such reports don’t make me especially happy, and I do have concerns about their veracity. There’s a big contrast between those statements and the political reality on the ground and there are several problems with these assessments. They claim that the PA is now above the “threshold” for establishing a functioning state, that it has met these institutions’ various criteria for statehood eligibility. There’s a general problem in this sort of generic template approach to evaluating complex governance issues, wherever they might be. In the Palestinian case the real problem is that such criteria and arbitrary thresholds are irrelevant to the reality and to the big elephant in the room of Palestinian governance, namely the Israeli occupation.

So today, what actually matters is: what happens in September when all that changes, when at best the formal diplomatic status becomes the “State of Palestine”? What’s going to make this virtual state turn into a real state? Nobody seems to be addressing that. All the talk is about polishing this virtual state, reforming and fixing it, adding services here, privatizing there, saving money here and cutting budgets there. It’s like the manner in which donors and international institutions approach the performance of a normal middle-income country. The PA seems to assume that by the will of the people, the citizens who proved themselves being capable of respecting traffic signals, paying electricity bills and not carrying guns in public, statehood will “impose itself.” Somehow statehood “just arrives” in September because technically everything is ready.

RS: According to recent reports, Palestine seems to be doing quite well in economic terms. Is it?

RK: Well, we’re certainly witnessing an “economic bubble.” We saw this before in the 1980s and the 1990s, but the bubbles eventually burst or were crushed by Israeli tanks. Economic growth of 9 percent in 2010 was largely fueled by donors, aid and private investment recovery in the West Bank, as well as the booming illicit tunnel economy in Gaza. It’s no secret that “growth” is mainly taking place in Areas A and B, and not in Area C, the south of the West Bank and the Jordan valley, while Gaza and Jerusalem anyway are effectively excluded from the growth map. So it’s about half of the Palestinian people under occupation who are actually enjoying the economic recovery. [Editorial note: Under the Oslo accords, the occupied West Bank is split into three zones: Areas A, B and C. The PA has security control over Area A, and shares control with Israel over B. Area C, which accounts for 60 percent of the West Bank, is under Israeli control.]

The focus on reaching the threshold for statehood wasn’t a total waste of time. It certainly helped to organize, if nothing else, the image of a functioning state. All at the risk though that the PA will satisfy itself with the image of a functioning state and “citizens” will acquiesce in what appears a normal life. Welcome to Palestinian “economic peace!” Palestinians basically have to settle for that and dress it up as much as possible for an indefinite future without any scope for real economic policy-making that goes beyond service delivery and helps to create the conditions for ending occupation, rather than for coexisting with it. So, as a development economist, I’m instinctively wary of bubbles such as this, especially taking into account the specific historic trends and structural changes that preclude such growth from being developmental.

RS: Do you have any other concerns?

RK: Yes indeed, my second point is: There’s an assumption that things are so much better institutionally than they were in 2000 or 2005. Had these institutions been in place back then, what would have prevented the state from being functional? If you recall Oslo, the state was supposed to be established by the end of the 1990s. Five years were considered to be enough. It was assumed that whatever was in place could be turned into a state in one way or the other. Of course, today public finance transparency is improved, but ultimately the control of finance is still in the hands of one person, as it was under the supposedly corrupt [late Palestine Liberation Organization Chairman] Yasser Arafat. The main public institutions certainly function. They provide their services. But they were doing that before, too! It’s not as if they weren’t delivering services ten or five years ago or that what was preventing the state from being established was such a weakness.

According to the whole institutional reform scorecard that the PA and the donors are keeping, by such criteria, it’s only now that the Palestinian right of national self-determination may be addressed, since the Palestinians have now shown that they can govern themselves. So, does mean that the reason they haven’t been able to do so ever since 1988, when they first declared their independent state in accordance with UN resolutions, was because of their own institutional failings, which took the past twenty years to address? This is an unhelpful diversion from the real focus that is required for effective state-building and managing economic development of a war-torn economy.

My third concern is about the sort of economy that’s being established. Let’s assume that by September there’s a Palestinian state running and Israel withdraws. What sort of economy are they thinking about? They’re talking about a very open trade system, perpetuation of the Paris Protocol framework and so-called “customs union,” compliance with World Trade Organization standards, no autonomous monetary or macroeconomic policy, fiscal responsibility, etc. But you don’t need an UNCTAD economist to tell you that this is the wrong approach for such a situation.

RS: According to the latest figures, manufacturing output has declined. What are the implications of this trend for the future of the Palestinian economy?

RK: We at UNCTAD have estimated that about one third of the productive capacity that existed prior to the second intifada was lost. Certainly industry has to be invested in as part of strengthening the components of domestic demand. I don’t see any of that happening in Palestine, except anecdotally in certain niche sectors. Why not? How do you come out of a conflict with a war-torn economy wanting your state to stand on its own feet, if it has not domestic industrial productive capacity? All these reports show that there’s hardly been any change in the high unemployment and poverty rates. So, propagating export-led growth and development is simply wrong. It has not worked in the Palestinian context and it only worked for others in very different stages of development. It may come later, but definitely not now. Also, if in September we’re going to have something like a Palestinian state, its access to markets will totally remain in the hands of Israel. So, what sort of export-led growth are we talking about? All the recent experiences of neoliberal market fundamentalism around the world and many experiences of export-led growth strategies in similarly weak economies in Africa, not to mention North Africa, have evidently failed, and in the latter they’ve done so spectacularly! Yet, the PA is making plans for such an economy. There’s a saying that fits the case perfectly: “They are going to the Hajj when all the pilgrims are coming back.”

RS: What are the key pillars of the PA’s neoliberal agenda?

RK: In the West Bank at least, neoliberalism has permeated pretty much every area of economic policy and social life. Of all the options available in its fiscal, trade, monetary, labor, industrial or foreign investment attraction policy, the PA chose the neoliberal path, for example pursuing full integration with the Israeli economy or liberalizing our trade regime to the maximum. Export-led development, as I’ve mentioned before, is said to be the only optimal policy for developing countries and integration with the more advanced Israeli economy the best option. There’s an assumption that such a development strategy will allow integration with the long-term trend of the Israeli economy whereby the statistics brutally show that income divergence is the only sure trend in Palestinian-Israeli economic relations for forty years.

Indeed, if we look at the Arab economy in Israel since 1948, basically the relation of Palestinian economic resources to Israeli capital and development prerequisites is the same. Furthermore there is this all pervasive discourse about the need for the Palestinian state to enable “private sector led growth.” This is a bit of a canard since the Palestinian public sector is non-existent as an economic agent and nowadays, there’s hardly anything left to privatize. Yet ordinary people suffer from privatization.

Let’s take electricity distribution as an example. Go to the Jordan Valley or to the south of the West Bank at night and you’ll see hillsides of villages using candle light. Prepaid electricity meters were forcibly introduced as part of the PA budget pruning exercises in line with Washington consensus provisions, but of course many poor people can’t pay and the usual “social safety nets” are simply neglected.

In my opinion the blind adoption of such a policy agenda is one of the PA’s most grievous mistakes; indeed, it is inimical to development and liberation, the two things the Palestinian people need above all. What does the Palestinian economy need? It needs to be rebuilt. The productive capacity needs to be reconstituted deliberately and investment accordingly directed. Sustainable revival can’t simply be market-led. Decisions have to be made: What sort of industry do we want? What sort of agriculture? What about food security? What about natural resources: the natural gas fields, the Dead Sea resources, water? Where is the policy and what are the institutions of the sovereign independent Palestinian state to deal with these strategic aspects of national economic security?

RS: When did the neoliberal turn begun?

RK: It’s going back to the 1990s, to the Madrid Peace Conference, the Oslo peace process, globalization and the incremental involvement of the international financial institutions in Palestine. Particularly the World Bank and increasingly the IMF have left their traces in the policy-making elites’ way of thinking. And of course Prime Minister [Salam] Fayyad’s own background matters: he comes from the IMF, while the CEO of the Palestinian Investment Fund, Muhamad Mustafa, was bred in the World Bank next door. I don’t blame them since they really can only think of these issues in that same frame of reference. But it’s surprising however that there’s so little alternative economic thinking coming out of Palestine. On everything else, in terms of activism, human rights, civil society engagement, etc., there’s intellectual thinking and Palestine remains a vibrant avant garde. So why is it that only a few people question the PA’s neoliberal approach? That’s why Sobhi Samour and I wrote that article in the Journal of Palestine Studies. Things are so obvious, but nobody says anything about it and we felt that it needed to be said, in this case by two Palestinian economists.

RS: How do force, consent and persuasion work in the Palestinian context?

RK: The emphasis on the Palestinian reform, institutional building, development expenditures and showcasing has provided the security component, especially the successful partnering with US military trainers and the Israeli army in securing a “calm” in the West Bank since 2007, presumably bringing down the military burden and cost of occupation in the process. Also, after all these years of unsuccessful struggle, modernization, transition to some kind of normalcy, peace and normal life is very appealing and persuasive, while PA jobs sustain a hard core of at least a third of the employed — that’s quite a constituency for persuasion!

Consent goes further than that in the sense that there are elites who were waiting for this kind of situation. In the West Bank there are plenty of building contractors, luxury service providers, property developers and speculators who are currently making good money, while in Gaza a new elite of several hundred entrepreneurs and rent seekers has arisen through the illicit tunnel economy. I think all of these are important supporters of the current “consensus.”

RS: Does the division between Fatah and Hamas contribute to this?

RK: With regard to the West Bank, the division certainly has been a facilitating factor. With Hamas involved in policy-making, this agenda would have faced a lot more resistance, as the resulting poverty and unemployment would have caused unrest and political pressure among Hamas’ constituency. However, there’s currently a lot going on in the region, as people reject authoritarian rule. As much as these revolutions were political, they’ve been socioeconomic ones, too. This wave will hit Palestine in one way or the other regardless of the dilemma of what to do with the occupation.

RS: What about the Palestinian 15 March movement that seeks to end the division?

RK: The younger generation doesn’t trust anybody, I think. The 15 March movement, even though it’s quite small, indicates that many youth have lost respect for Hamas, Fatah or the PA under Fayyad. It’s a generational issue, too. Among the middle class, there’s of course some dependency. Also, there’s a very powerful entrepreneurial capitalist class. It’s the people involved in these big development projects like the industrial estates, model cities and gated communities or gas projects. This class has certainly flourished under this PA, but even before they’ve done quite well. These people have a big stake in keeping the whole thing working. I haven’t seen much of major long-term investment projects though. Basically it’s residential construction. The level of construction and its share in the gross domestic product has traditionally been high in Palestine, even in the 1980s. But it just takes one Israeli tank in Ramallah to bring all these billboards, glass fronts and traffic signs down. Just one tank and it’s finished. Let’s hope that it doesn’t end like that.

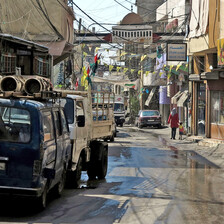

Image courtesy of Raja Khalidi.

Ray Smith is a freelance journalist and an activist with the autonomous media collective a-films.