The Electronic Intifada Ramallah 10 March 2015

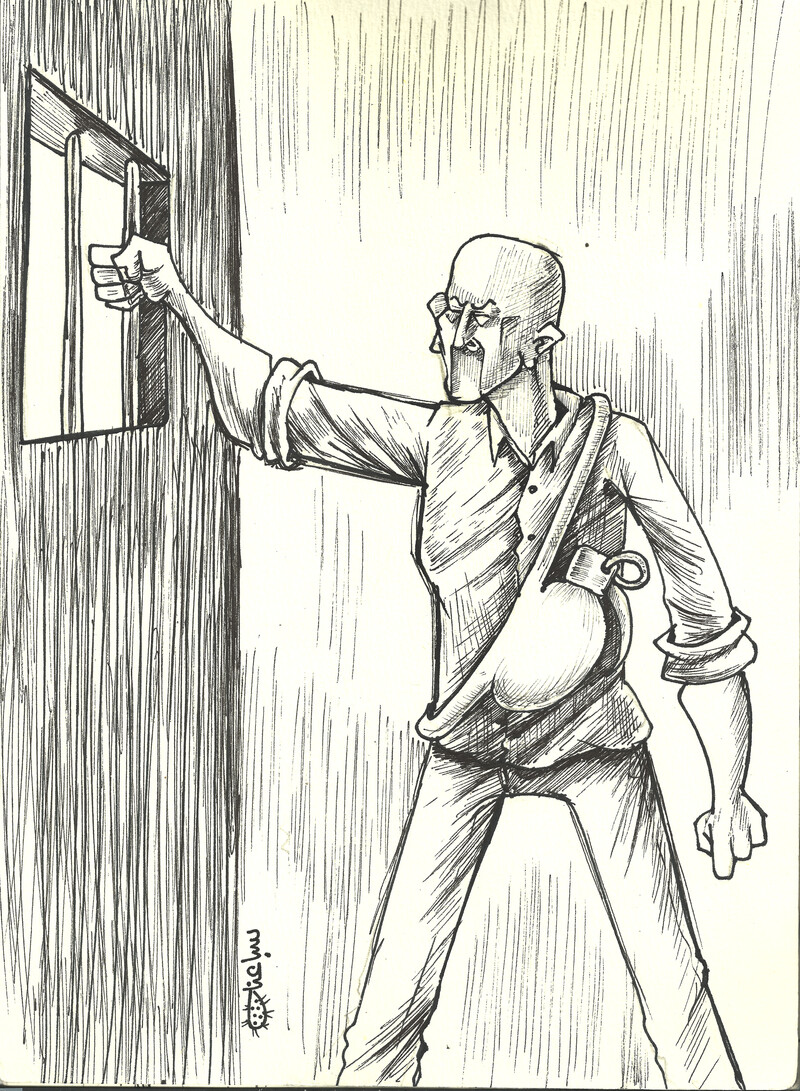

Artwork by Mohammad Saba’aneh for The Electronic Intifada

Hassan Ishtayeh runs a lively restaurant named Abu Razi’s Shawarma in the occupied West Bank city of Ramallah. The 47-year-old is frequently greeted and hugged by his customers. Quite a few of them have something in common with him: they have been locked up in Israel’s jails.

“I know a lot of people because I was arrested eight times since 1987,” Ishtayeh — known to friends and family as Abu Razi — told The Electronic Intifada. He was targeted because of his activism with the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), a left-wing political party.

“At some points, hunger striking was the only weapon we had to fight administrative detention, the poor treatment or other injustices the [Israeli prison] authorities subjected us to,” Ishtayeh said. He participated in group hunger strikes every time he was behind bars. Administrative detention involves holding a prisoner without charge or trial.

According to Addameer, a Ramallah-based prisoners rights group, more than 6,000 Palestinians are being held in Israeli jails.

In January, Khader Adnan, a Palestinian activist repeatedly imprisoned by Israel, launched a one-week hunger strike in protest of having been put in administrative detention and held in solitary confinement. Adnan famously went on a hunger strike in December 2011 for 66 days in protest of his administrative detention, eliciting global solidarity actions.

“Constant struggle”

Artwork by Mohammad Saba’aneh for The Electronic Intifada

Ishtayeh first participated in a hunger strike with other prisoners in November 1987. He had been arrested shortly before the first intifada erupted.

“Every time I’ve been in prison since then, I was part of a hunger strike. For me it’s impossible not to join in because from the moment you’re detained there is a constant struggle — 24 hours a day — with the prison authorities.”

“In those days, we often went on hunger strike for better conditions. For instance, the guards wouldn’t let us have clean bedsheets for weeks at a time, so we went on hunger strike until they did,” he said. “Another time, I was part of a hunger strike for a television and access to books. These are basic rights.”

Ishtayeh said that it is “crucial to understand” the many different types of hunger strikes that Palestinian political prisoners use in Israeli jails. “There are protest strikes that are used to fight Israel’s neglect of prisoners and as an attempt to improve the living conditions,” he explained.

He noted that prisoners use solidarity strikes to bring attention to injustices that may not be directly related to their own living conditions. “There are also open hunger strikes,” he said. “We launch a strike without a set end date and with the intention to not eating until [the Israeli authorities] comply with [prisoners’] demands.”

Five years without charge

In 2004, while he was director of the Nablus Prisoners Committee, Ishtayeh was yet again arrested and sentenced to four and a half years in prison for charges related to his activism with the PFLP.

“During this period, we went on hunger strike inside the prisons a lot,” he recalled, explaining that the second Palestinian intifada was still taking place outside the prisons.

Ishtayeh has been put in administrative detention on three occasions, most recently in 2012. He said he was held for a total of five years without charges.

Artwork by Mohammad Saba’aneh for The Electronic Intifada

In February, more than 460 Palestinians were being held in administrative detention, according to Addameer.

In April 2012 Palestinian political prisoners launched a mass hunger strike against Israel’s use of administrative detention. “We began to speak to all the different political parties in prison — Fatah, Hamas, the Islamic Jihad and the others. We decided to start the strike on 17 April.”

“At the beginning, there were 37 PFLP prisoners on strike and four from the Democratic Front [for the Liberation of Palestine],” he said. “Another thirty from Fatah, and around thirty from Hamas joined us after we had already been on strike for three days.”

“Prisoners from other jails started to join quickly,” he said, explaining that Israeli authorities moved immediately to end the strike. “It had already spread to most of the prisons and they couldn’t do anything about it.”

More than 2,000 prisoners joined the strike. The Israeli prison authorities eventually conceded to several of their demands. They included increasing family visits for prisoners from Gaza, improved healthcare and expanded access to education inside prisons.

Punitive measures

Israeli prison guards “started to put fruit trays and meals in front of the cells of prisoners on hunger strike,” Ishtayeh said. “They provoked us and tried to convince us to eat. During visits to the prison clinics, the doctors and guards would try to convince the hunger-striking prisoners to eat something.”

Human rights groups have condemned Israel for taking punitive measures against hunger-striking prisoners.

When Samer al-Barq went on an open-ended hunger strike against his administrative detention during the summer of 2012, Addameer reported that the Israeli authorities tried to put pressure on the hunger strikers by surrounding them with people who would eat in front of them.

Other hunger-striking prisoners have been punished with verbal assault, physical beatings and by being held in solitary confinement.

“They did whatever they could to try to break our will to struggle,” Ishtayeh said. “The authorities make it very difficult, but they cannot stop most hunger strikers from resisting.”

Another mass hunger strike took place during the summer of 2014.

Dozens of prisoners refused food for 63 days in protest of administrative detention. According to the Palestinian Prisoners Society, it was the longest mass hunger strike in Palestinian history.

Artwork by Mohammad Saba’aneh for The Electronic Intifada

As Israel launched a military offensive in the West Bank, the number of Palestinian detainees and administrative detentions skyrocketed. The prisoners eventually ended their hunger strike without an agreement by Israel to entirely cease the use of administrative detention.

“That doesn’t mean that hunger strikes won’t continue to bring victories” for Palestinian prisoners in Israeli lockup, Ishtayeh said. “It just means that they have to be carefully calculated and strategically planned.”

One example of a victory occurred last December when a solidarity hunger strike launched by more than one hundred prisoners concluded with Israel ending the 570-day solitary confinement of Nahar al-Saadi.

“We learned that hunger strikes don’t lose their effectiveness,” Ishtayeh said. “They are a thorn in the side of the Israeli occupation.”

Patrick O. Strickland is an independent journalist and regular contributor to The Electronic Intifada. His website is www.postrickland.com. Twitter: @P_Strickland_

Mohammad Saba’aneh is a Palestinian cartoonist based in Ramallah. Twitter: @sabaaneh