The Electronic Intifada 12 July 2018

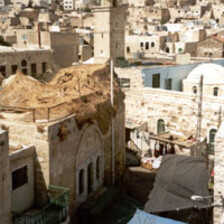

Israeli soldiers staff a checkpoint in the Bethlehem area.

ActiveStillsIsrael’s military checkpoints in the occupied West Bank regularly cause nightmares for Palestinians. They prevent us from traveling freely from one town to another, commuting to work or school, accessing medical services and visiting relatives.

Some of these checkpoints were established approximately two decades ago in a failed attempt by the colonizing power to normalize oppression. One of these is the notorious Container checkpoint in the Bethlehem area.

On 23 June, I had a frightening encounter with Israeli forces at this checkpoint.

That evening I was among seven passengers in a shared taxi traveling from Ramallah to Bethlehem. The taxi had to slow down as we approached the checkpoint – which includes a concrete watchtower.

There was a long line of vehicles ahead of us, moving very slowly. The message sent out was clear: we should expect to be delayed.

The passengers in our taxi chatted about news reports they had seen. According to those reports, a Palestinian had been shot at the checkpoint that morning.

Our driver, as it happened, could confirm that the reports were true.

He had been at the checkpoint earlier in the day and had seen the man, 34-year-old Maher Jaradat, lying on the ground after being shot. Our driver pointed to the spot where Jaradat had lain.

Israeli soldiers prevented a Palestinian ambulance from reaching the wounded man, our driver added.

Jaradat had been bleeding on the sidewalk for more than an hour before an Israeli military ambulance reached him. When the ambulance arrived, Jaradat was arrested.

Our driver told us the man had been shot in the leg while walking towards the soldiers at the checkpoint. Palestinians are not allowed to cross the Container checkpoint by foot; only in vehicles.

Other accounts indicate that Jaradat was shot for arguing with soldiers or attempting to stab one of them.

After the shooting, the checkpoint was shut down. Hundreds of vehicles had to wait on either side of it before it was reopened in the afternoon.

Painful memory

Around 9 p.m., it was our turn to cross the checkpoint.

I was sitting in the front seat beside the driver. In the dim light we approached a number of heavily armed soldiers. They were surrounded by concrete blocks and cabins.

As we came closer to the soldiers, we suddenly realized that one of them was pointing his assault rifle directly at us.

I felt like I was unable to breathe.

A painful memory came back to me. I recalled the time I was shot in the leg by an Israeli sniper. That shooting occurred in Bethlehem during December 2015.

With his assault rifle pointed at our faces, the soldier ordered us to pull into the right lane. He seemed to be instructing the drivers of all Palestinian-owned vehicles – with green license plates – to pull over into the right lane, so they could be inspected.

Israeli-owned cars – bearing yellow license plates – were, by contrast, allowed to pass through without being checked.

All the passengers in our taxi went silent and the driver rolled down his window. Terrified, I lifted both my hands to express confusion. The soldier kept his gun pointed at us.

“What is wrong?” I asked, as calmly as I could.

“You,” the soldier replied. “You are wrong, you are dangerous, this car is dangerous. And all of you are dangerous.”

“But you are the one holding a gun,” I said. “Not us.”

Hate and anger

At that moment all I could think of was the man who had been shot at the checkpoint earlier that day.

The young soldier pointing the gun at us seemed to only hear his own voice. It seemed as if he was unaccustomed to hearing the voices of Palestinians, that he was unfamiliar with having his actions questioned by the people he oppressed.

His eyes and voice were saturated with hate and anger.

He demanded the IDs of all the passengers in our taxi, then handed them to another soldier while he moved to scrutinize the next vehicle. The female soldier holding our documents dictated our ID numbers to another soldier sitting inside a cabin and looking at a computer screen.

I immediately thought of Israel’s “wanted list,” which includes huge numbers of Palestinians linked directly or indirectly to resistance activities.

Among those considered as “wanted” are former political prisoners and their relatives, the relatives of people killed by Israel and people who participate in protests. Everyone on the list is at risk of being arrested or subjected to movement restrictions.

None of us in the taxi was on the “wanted list.” Our IDs were returned to us and we were allowed through the checkpoint.

As we traveled on, I thought about the man who had been shot that morning. It is possible that the soldier who pulled the trigger was questioned by someone of higher rank. Yet the soldier is unlikely to face any serious penalty. It was evident from the way the troops we encountered behaved that they feel superior to us, that they think we must be controlled.

We all remained silent until we reached Bethlehem.

Traveling from Ramallah to Bethlehem used to take me half an hour. That was before the Israeli occupation shut down the road originally connecting the two cities and before Israel built its massive apartheid wall in the West Bank.

My journey that evening took three hours.

Israel steals our land and water. And our time.

Rehab Nazzal is a Palestinian-Canadian artist, currently living in Bethlehem and teaching at Dar al-Kalima University College of Arts and Culture.