The Electronic Intifada 31 March 2005

30 March 2005 marked the 29th anniversary of Yum El-Ard (“Land Day”) — the first mass political protest of Arab citizens of Israel, now commemorated as a national day for Palestinians worldwide. Sharif Hamadeh interviews Fr. Shehadeh Shehadeh, the activist-priest who headed the first protest in 1976.

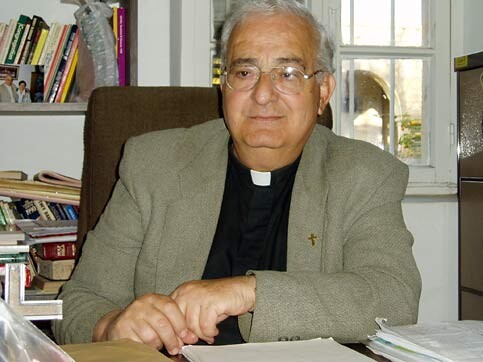

HAIFA, Israel — Fr. Shehadeh is a worried man. “People here are not very happy,” he says, referring to the Palestinian minority in Israel. “I’m always optimistic and I always pray for peace and work for peace - I even have a committee called Clergy for Peace - but at this time, I’m very pessimistic.”

Now 65 years old, Fr. Shehadeh spends a moment wondering openly whether his pessimism can be attributed to his age, before dismissing the possibility. “I don’t think it’s my age,” he says finally, “I think it’s my experience.”

Fr. Shehadeh has more experience than most. Currently serving as the priest at St. John’s Episcopal Church, the chairman of St. John’s School in Haifa, and the vice chairman of al-Jebha - the Democratic Front for Peace and Equality, Revd. Canon Dr. Shehadeh Shehadeh has a history of combining his pastoral responsibilities with political activism. Almost 30 years ago this month, it was Fr. Shehadeh who, as chairman of the National Committee for the Protection of Lands in Israel, headed the first organized mass protest of the Palestinian minority in Israel against the state’s treatment of its Arab citizens.

On 30 March 1976, Fr. Shehadeh and his fellow activists in the Committee staged a major strike of Israel’s Palestinian citizenry, mobilizing the community to reassert both its rights and its identity through collective direct action. As the pastor relates, the state-wide strike was intended as a peaceful protest against the government’s planned expropriation of over 20,000 dunams of land (more than 5,000 acres), mostly located in the Galilee in the north of Israel, but also in the Naqab (Negev) and in the Triangle, in the south and center of the country, respectively.

The expropriation of Palestinian land has been a prominent feature of Israel’s discriminatory approach to land and planning since its birth over half a century ago. Immediately prior to the state’s establishment in 1948, it is estimated that only six per cent of historical Palestine was under Jewish ownership. Over the past 56 years however, large tracts of Arab-owned land have been systematically confiscated or otherwise appropriated under law and taken into the possession of the state or Zionist institutions that are mandated to work exclusively to benefit the Jewish people, such as the Jewish Agency and the Jewish National Fund. Numerous laws and policies have brought about state control of over 93 per cent of the land in Israel.

For Fr. Shehadeh, attempting to dispossess Palestinians of their land through confiscation is simply one tactic Israel uses in its ongoing pursuit of “less Arabs and more land.” “Even in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip they are doing the same thing,” he says, “They are making life difficult for people so that they will leave, and they are expropriating more land.”

In 1976, the government considered the continued expropriation of land in the Galilee, Naqab and Triangle regions, where sizable Palestinian populations remained, to be of such critical importance that it responded to the organized protest strike with crushing military and police force. By the conclusion of the day’s events, what had started out as a peaceful state-wide protest had ended with the deaths of six unarmed Palestinians in the Arab villages of Sakhnin, Arabeh, Kufr Kana and Taibeh. Hundreds of others were maimed or injured.

Yum El-Ard or “Land Day,” as it was named, is now marked by Palestinians on both sides of the Green Line and in the diaspora on an annual basis. Commemorated by strikes and marches, it effectively serves as a national day for Palestinians worldwide - one of the most important dates in their calendar.

As with many historic events in the Middle East, Land Day’s roots lie with the activities of a small group of committed individuals. At the first organizational meeting, held in Haifa and arranged by Rakah - the New Communist List, some 25 people were invited to discuss strategies for opposing the government’s plans for expropriating further Palestinian land. Among them was Fr. Shehadeh, then a 36 year-old pastor in Shafa’amr who was unaffiliated with any political party.

In the face of the governmental expropriation effort, Fr. Shehadeh’s describes his decision to become involved in the first Land Day protest as the convergence of his religious and political vocations. “I am a pastor and I believe that a pastor should understand the pain of the people,” says the priest. “It aches people when their land has been taken. It is as though a part of their body has been taken. It is very painful… My faith did not allow me to stand aside.”

In cooperation with likeminded others, the movement against the planned expropriation gathered pace. Especially keen to involve villages earmarked to lose land in the government’s plans, the activists invited the heads of local councils in the Galilee and the Triangle to a second meeting, held in Nazareth and hosted by the city’s then poet-mayor, Tawfiq Ziad. As Fr. Shehadeh recalls, over 100 people attended the meeting and left adamant that they would prevent the planned expropriation from taking place - “No matter what.”

It was at that second meeting that the burgeoning Committee also decided to initiate a concerted drive to inform the general Palestinian public in Israel that organization was taking place to defend their lands against the government’s scheduled expropriation efforts. In cooperation with other political allies, the group began to disseminate pamphlets and fliers all over Israel, announcing the date for a public meeting to be held in a Nazareth cinema on the issue of the proposed expropriation.

Fr. Shehadeh’s narration slows down as he recalls his profound amazement at the response of the Palestinian community in Israel. “The meeting was enormous,” he says, as if still attempting to comprehend the depth of public interest. “We did not expect that. We did not expect that people would come in such numbers. Thousands upon thousands of people came. The cinema had the capacity for 300 or 400 people, but people had gathered in all the corridors of the building and in all the streets around it.”

Such popular support would prove to be the Committee’s most precious resource. Letters the Committee wrote to Members of Knesset went largely unanswered, whilst an impromptu meeting with the ruling Labor Party in the Knesset resulted merely in the party affirming that it would not reconsider its plans to expropriate private Palestinian land.

But Fr. Shehadeh and his fellow Committee members reacted to governmental intransigence with an intensive grass-roots campaign - visiting the villages that were to be affected by the expropriation, informing residents of the government’s plans and their likely consequences, and even photographing parcels of land destined for confiscation whose coordinates would then be sent to villages to prompt local council discussion on the issue. “I used to go to public meetings three or four times a week to tell people that we intended to organize a strike if the government doesn’t listen to us,” he recalls.

Then, on 18 March 1976, just 12 days before the strike was scheduled to take place, Shehadeh Shehadeh was invited to attend a meeting in Shafa’amr, hosted by Ibrahim Nimr Hussain, the town’s mayor, and attended by the heads of local councils, to discuss the Committee’s planned strike. It soon became clear that the mayor expected the Committee to respect the councilors’ decision over whether or not to strike, and to defer to their judgment. As Fr. Shehadeh recounts, the overwhelming majority of local council heads, most supported by the Labor Party, voted against the strike, but not before the pastor had stormed out of the building in protest at the idea that the Committee should answer to the heads of the local councils, rather than directly to the people.

And the people made their will known. According to Fr. Shehadeh, when the decision of the heads of local councils was publicized to young men awaiting its announcement, they began throwing stones at the municipal building in which the local councilors had debated the issue, preventing the councilors from leaving. As the protest intensified, police officers rushed out of a nearby building where they had been hiding in wait and, “began attacking these youngsters and throwing tear gas.”

That night, says Shehadeh, the Committee held an emergency meeting in Sakhnin (one of the towns due to lose land under the governmental plans) after which, the Committee publicized its intention to hold a protest on 30 March against the government.

The original plan to stage a demonstration outside the Knesset was cancelled at the last minute, when the Committee was denied a permit to demonstrate. Instead of risking the mass arrest of its supporters, the Committee urged people to register their opposition to the ongoing state expropriation of their land by staying at home in their villages and striking.

Then, early on the morning of 30 March 1976, Fr. Shehadeh received a phone call alerting him to the news that the state had ordered the military to enter the striking villages. Residents responded with stone throwing and spontaneous demonstrations while the military used live fire, with fatal results. The victims whose lives were lost were: Khadija Shawahneh, Raja Abu Raya and Khadr Khalayleh of Sakhnin; Kheir Yassin of Arabeh; Mohsen Taha of Kufr Kana; and Rafat Zohiri of Nur Shams refugee camp in the West Bank, who was killed in Taibeh.

For Fr. Shehadeh, the state’s resort to violent confrontation with strikers that day was merely an example of the long-term strategy that Israel uses to control Palestinians on both sides of the Green Line. “Israeli policy has always been to treat the Palestinians with an iron fist,” he says. “I know that, and I heard that several times, even from police people. They would say, ‘Only through power can you be treated. You don’t even know what democracy is.’ So that’s how we are treated.”

Despite the violence, Fr. Shehadeh estimates that between 70 and 80 per cent of the Palestinian public in Israel participated in the strike on 30 March 1976. He summarizes its significance for Palestinians in Israel by proudly quoting his late friend Saliba Khamis: “On Land Day, the genie came out of the bottle.”

This year, as Palestinians commemorate the 29th anniversary of Land Day, foremost on Fr. Shehadeh’s mind are the land grab that he says the state is currently undertaking in the West Bank through its construction of the separation wall, and the divisions he believes the government is engineering between the different faith groups of the Palestinian community in Israel.

Citing the recent clashes that occurred between Druze and Christians in Mghar as an example, Fr. Shehadeh describes Israel as employing a classical “divide and rule” approach to its Palestinian citizenry.

“This is the terrible disease in Palestinian life in this country,” he says, “And Land Day, to a certain extent, and for a period of time, succeeded to remove these kinds of differences between the Palestinians themselves. Unfortunately, the government has succeeded to divide us again, and Land Day doesn’t unite people as it used to.”

Nevertheless, Land Day’s legacy and commemorative value lies not only in the fact that the Palestinian minority in Israel was galvanized to take unified action against the state’s discriminatory policies, but that it exposed the common plight of Palestinians everywhere.

“Without land we have no roots in this country,” says Fr. Shehadeh, “The land is our roots. The land is not only a place where you plant eggplants and cucumbers - it is our national home. I am a Palestinian and this is my homeland.”

Sharif Hamadeh is a Human Rights Advocacy and Development Fellow with Adalah. Adalah is an independent human rights organization, registered in Israel. It is a non-profit, non-governmental, and non-partisan legal center. Established in November 1996, it serves Arab citizens of Israel, numbering over one million people or close to 20% of the population. Adalah (“Justice” in Arabic) works to protect human rights in general, and the rights of the Arab minority in particular. This interview first appeared in Adalah’s Newsletter, Volume 11, March 2005. For more information, see www.adalah.org.

Related Links