The Electronic Intifada 21 July 2008

With such dreams in hand did 19th-century Western travelers visit the Levant (present-day Syria, Lebanon, Israel-Palestine and Jordan) in search of the biblical “Holy Land.” Thus they came, saw and recorded their fantasy and their disappointment, and bound them together into a beautiful canon of half-truths and outright lies that first helped shape popular perception and finally were used to help justify the colonization of Palestine.

Who could imagine “a land without a people” without William Thackeray’s vivid depiction of Palestine as “parched mountains, with a grey bleak olive tree trembling here and there; savage ravines and valleys paved with tombstones — a landscape unspeakably ghastly and desolate …”?

Who would have felt inspired to “make the desert bloom” without Herman Melville’s description of “Whitish mildew pervading whole tracts of landscape — bleached-leprosy-encrustations of curses-old cheese-bones of rocks — crunched, knawed, and mumbled — mere refuse and rubbish of creation … all Judea seems to have been accumulations of this rubbish”?

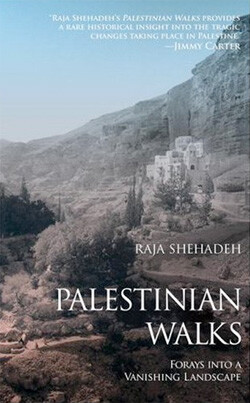

Yet, these accounts also compelled Raja Shehadeh, founder of the human rights organization Al-Haq, to provide a counter-narrative, in Palestinian Walks: Forays into a Vanishing Landscape. “The accounts I have read do not describe a land familiar to me,” Shehadeh writes, “but rather a land of these travelers’ imaginations. Palestine has been constantly reinvented, with devastating consequences to its original inhabitants.”

European, and later Zionist colonizers, traveled to Palestine looking for ancient Israel. Many wrote travelogues that silenced Palestinian history, says Shehadeh, and paved the way for the Jewish state to take control not only of the land but also of Palestinian time and space.

But here is a travel memoir that crosses no continents, only hills and valleys; that searches for recent present rather than distant past, and celebrates the real and the ordinary in order to debunk the imagined extraordinary. Its title ironically evokes the map-filled travel guides of tourists visiting natural parks. But Shehadeh’s text runs counter to the world of maps, containing, he reveals, not a single walk. Rather, this is an account of six sarhat, the plural of sarha, or to wander.

“A man going on a sarha,” he writes, “wanders aimlessly, not restricted by time and place, going where his spirit takes him to nourish his soul and rejuvenate himself. But not any excursion would qualify as a sarha. Going on a sarha implies letting go. It is a drug-free high, Palestinian style.”

The text itself resembles a sarha, meandering from the hills of Ramallah, to Shehadeh’s family history, into Palestinian history, and finally the foreboding present. Waist-deep in wildflowers, readers wade through a land that tells its own stories. We learn that Shehadeh’s family belonged to one of the five founding clans of Ramallah 500 years ago, but left farming life for urban Jaffa. In 1948 they were expelled and much of the family found itself back in Ramallah, displaced urbanites who rarely visited the city’s surrounding hills. Not until returning from law school in London did Shehadeh, preoccupied by “Israel’s long-term policies toward the Occupied Territories,” begin to wander out of the city of his birth.

Shehadeh writes: “The hills began to be my refuge against the practices of the occupation, both manifest and surreptitious, and the restrictions traditional Palestinian society imposed on our life. I walked in them for escape and rejuvenation.” Foreign to the hills, he at first got lost, but finally he “began to have an eye for the ancient tracks … and for the new, more precarious ones, like catwalks along the edge of the hills, made more recently by sheep and goats in search of food and water.” The sarha finally proved more natural than urban navigation: “I found myself to be a good pathfinder even though I easily got lost in cities.”

Shehadeh takes us through rich passages as he perches on a large rock, tests his lungs running up a hill, or rests to take in a view:

“All you can see are hills and more hills, like being in a choppy sea with high waves, the unbroken swells only becoming evident as the land descends westward. This landscape, we are told, was formed by the tremendous pressure exerted by tectonic forces pushing toward the east. It is as though the land has been scooped in a mighty hand and scrunched, the pressure eventually resulting in the great fault that created Jordan’s rift valley, through which runs the River Jordan. … Its surface is not unlike that of a gigantic walnut.”

On that first sarha in 1978, we stumble accidentally onto Shehadeh’s uncle’s old qasr, a stone hut long abandoned: “It was as though in this qasr time was petrified into an eternal present, making it possible for me to reconnect with my dead ancestor through this architectural wonder.” We meet Abu Ameen, who rejected the family’s city life to raise his family in this house while supporting himself as a stonemason. Reflecting on the slow erosion of these lands under settlement construction, Shehadeh wonders what his uncle would think to see it now. “Would his spirit be brimming with anger at all of us for allowing it to be destroyed and usurped, or would he just be enjoying one extended sarha as his spirit roamed freely over the land, without borders as it had once been?”

Unlike the accounts of travel writers past, Shehadeh’s hills are full of people, not only the ghost of his uncle but also the plaintiffs he represents in court who seek to preserve their land from settlement use; old men meditating and young boys running around; the negotiators of the Oslo Accords who return from abroad with Yasser Arafat to rule the country, and the politicians who rise to challenge them.

Each sarha walks us through different and multifaceted aspects of Israel’s occupation, from the draining of the Dead Sea to irrigate settlement lands, to the concrete “poured over these hills” to support Israel’s expanding industrial zones, to the wall that not only isolates communities but also destroys their land and livelihood. Over time, the hills, robbed of simplicity, contradict themselves. They provide solace only next to grief, freedom only coupled with imprisonment, and sanctity never without danger. Finally, we find the hills that once provided Shehadeh with an escape from occupation have been transformed into its quintessential landscape, and Thackeray’s and Melville’s dreary accounts have been fully realized into the Jewish-only settlements that claimed them as inspiration. In this upside-down land, Shehadeh gets lost in a fearsome labyrinth of settler highways, and dodges bullets as Palestinian security forces shoot from a distance.

Honest, haunting and heartbreaking, this travelogue hits close to home while transporting us not only into Palestine’s telling geography, but also into our own daily paths, making us question how they, too, shape our lives.

Lora Gordon lives in Chicago, where she studies journalism at Northwestern University and works at a community health center.

Related Links