The Electronic Intifada 22 November 2010

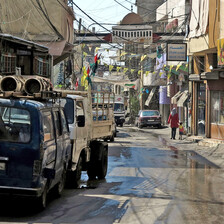

Palestinian refugees in Lebanon work in the informal sector to make ends meet. (Ray Smith/IPS)

BEIRUT, Lebanon (IPS) - Abu Yussif doesn’t want to talk about his work anymore. “It’s not going to help and nothing will change anyway,” he says. The tall, white-haired Palestinian has just returned from work and relaxes in his little garden in the Burj al-Shamali refugee camp near the southern Lebanese city of Tyre.

Abu Yussif is a pharmacist. But the massive discrimination against Palestinians in the Lebanese labor market has forced him to give up his profession and work as a taxi driver.

Palestinian refugees and their descendants have been living in Lebanon for 62 years. Unlike their relatives in Jordan or Syria, they face massive legal discrimination. Lebanon is not a signatory to the UN Refugee Convention, but it has ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and embodies the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in its constitution.

“According to the Refugee Convention, we’d have the right to access our host country’s labor market freely after three years,” says Suhail al-Natour at his office in Beirut. Al-Natour heads the Human Development Center, a Palestinian human rights organization. “After Palestinians were excluded from working in the public sector, the Lebanese government has restricted their access to employment in the private sector,” he says. “What was left were the lowest, hard jobs that most Lebanese wouldn’t do.”

Despite their residence in Lebanon, the approximately 250,000 Palestinian refugees are treated sometimes worse than foreigners. Access to jobs is restricted in various ways. Some professions are forbidden, many others require a work permit. In addition, approximately 30 liberal professions are controlled by syndicates. Further, Palestinians can’t run their own shops or companies, as they’re not allowed to own property.

For Palestinians, two options remain, says al-Natour: “Either they work inside the refugee camps, where the Lebanese state doesn’t exert its authority and forbidden jobs can be practiced. Or they work illegally and avoid inspections by the authorities.” The labor market within the impoverished refugee camps is limited. For well-educated Palestinians it hardly poses an alternative.

At sunset, Mahmoud Aga usually goes to a small plantation outside Tyre, where he grows some fruits and vegetables and relaxes after his workday. For 15 years he’s been working for a Lebanese company in Tyre. “Palestinians can’t join the engineers syndicate, so I’m forced to work illegally,” he says. Often working on-site, he’s directly dealing with Lebanese principals. “Currently I’m overseeing the construction of a public school. Of course the Lebanese authorities know I’m Palestinian.”

Aga enjoys working for his company and says his employer doesn’t exploit his situation by paying him a much lower wage, as it is often the case with Palestinians. “However, I have no social rights or insurance.”

Professional syndicates in Lebanon systematically deny Palestinians access. Sari Hanafi, associate professor at the American University of Beirut, explains: “Some of them have bylaws that restrict membership to Lebanese citizens. Others apply a reciprocity clause. However, the absence of a recognized Palestinian state makes the application of this principle impossible.”

In mid-August, the Lebanese parliament amended the Labor Law. It hasn’t touched the powerful position of the syndicates, however. Suhail al-Natour says that in theory the law is supposed to be above the syndicates’ rules. “Practically, however, the syndicates rule.”

The amended Labor Law obliges Palestinians to obtain a work permit for all jobs and eliminates the required fees. Al-Natour is far from happy, though: “There won’t be more Palestinians applying for work permits, because many procedural problems remain in place.” A contract with a Lebanese employer is a precondition for obtaining a permit. Al-Natour argues that employers wouldn’t issue contracts as they’d have to pay for social security and declare the wage. “They benefit from exploiting Palestinians, so they don’t want to change anything in the labor relations,” he says.

Similarly, Sari Hanafi stresses that neither the employee nor the employer have an interest in signing a contract. “Both would pay for the social security fund, knowing the employee wouldn’t benefit from it.” In summer, the parliament also amended the Social Security Law, allowing legally-employed Palestinians to benefit from end-of-service indemnities. However, they remain excluded from family, illness or maternity payments.

The Palestinians’ disenchantment with what’s been loudly praised as a rights “reform” has made them lobby even harder at the international level. At the ninth session of the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) within the UN Human Rights Council held in Geneva earlier this month, the review dedicated to Lebanon revealed the increasing awareness especially among European member states concerning the Palestinians’ dire situation in Lebanon.

Rola Badran, observing the conference for the Palestinian Human Rights Organization, says she’s satisfied with the UPR session. “It showed that the rights issue of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon is on the international agenda. The Lebanese delegation seemed annoyed and under pressure and repeatedly insisted on directly responding to states’ interventions that criticized the situation and recommended improvements,” says Badran.

Criticism mainly focused on the denial of property rights, discrimination on the labor market and the lack of freedom of movement, as most of the Palestinian camps are encircled by the Lebanese army. But Badran is pessimistic about Lebanon changing its policy.

“At the UPR session, they repeated their usual excuses by stressing Lebanon’s limited size and financial means.” And, with a slightly sarcastic laugh in her voice she adds: “Lebanon’s unwillingness is best illustrated by the delegation’s statement that the Palestinians’ presence has already been for so long and that Lebanon is still waiting for the Palestinians’ return to their homeland.”

All rights reserved, IPS — Inter Press Service (2010). Total or partial publication, retransmission or sale forbidden.