Beirut 25 July 2006

“This is our apple tree, and this is our lemon tree. And this is our house in our village,” Hadi said, trying to explain his drawing to me.

“Do you think that the Israelis ate the apples?” he asked suspiciously.

“Of course they ate them; do you think they left them for you? They eat the green and the dry (el akhdar wel yabes),” his friend Ali quickly responded.

“It was full of apples, and I was waiting them to ripen, evey day I look to see if any of them is ready. I like apples; if they take the lemon, it is okay, but I hope the apple tree will be full when I get back.”

Hadi ignored the comments of his colleague in displacement, Ali.

“I do not think they ate them,” he mused aloud. “They haven’t invaded Ya’ater yet, they are just shelling from the air. I am sure your apple tree is still intact waiting for you to come back for you to water it so it ripens and you eat its fruit,” I said to Hadi.

Hadi is one of almost 300 displaced children who ended up in one of the schools of Beirut, Rmel El Zarif School, where four to five families are staying in the same classroom. He is ten years old and from Ya’ater, a village at the borders with 1948 Palestine. Zahi has been in this school/shelter with his family and 500 more families,mainly from the south of Lebanon and the Suburbs of Beirut, for more than ten days now.

Ali, the other child, is from the southern part of Beirut, and who ended up in the same school as Hadi “all by chance,” as Ali’s mother explained. “The taxi driver kept driving until we found this school, and he dropped us here, we had no say. We simply escaped and left everything behind … We left with our pyjamas on, I even forgot to get them any clothes to put on, we were so scared.”

Many organizations and volunteers have started to work with children who were displaced with their families from many parts of the country, and who are now filling the schools, parks and different establishments in Beirut. The goal of current efforts and programs is first to encourage the children to express their feelings and anxieties about the war, and second, to give some time to their parents to relax a bit during the days.

In addition to drawing, many volunteers are reading with children, singing, playing, or even just sitting and talking. Although the children were asked to draw freely, i.e., they were not asked to choose a certain theme, most of their drawings depicted houses.

Darine, an eight-year-old from Shayyah, in the suburbs, drew a house with three sides.

“The fourth side was hit by a missile,” she exlained.

Nour, who is ten and from the Beirut suburb of Bir El-‘Abed, drew a house hit by a missile that smashed its roof and penetrated in the room and left the table broken. And although Zeyneb decided to draw a hotel, with the Abou Ali grocery on the side, the reason why she drew the hotel was, as she explained, to make a place “where all the displaced would stay instead of sitting in a school sleeping piled up in the ground as if it is Doomsday.”

Zeyneb is a 13 year-old from Tariq al Matar, the Airport Road, and was among the first residents of this shelter, since the airport was among the first targets of Israel.

“We left the second day of the shelling, when they hit the airport. The sound of the shelling was so loud, I was so scared and we heard screams from everywhere. When the shelling stopped, we left with many other neighbors in a minibus and ended up here. We were among the first to arrive to this school; many people started to come in the days after, and in the room where I stay now, there are eight families. Forty people sleep in the same room at night, men sleep outside though” Zeyneb said.

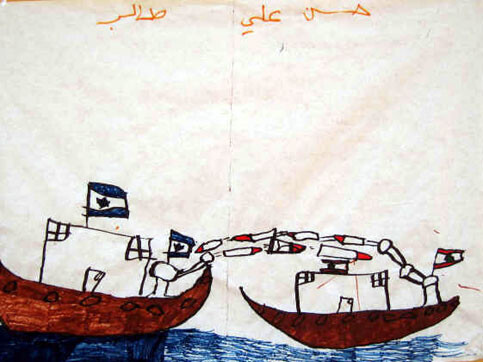

Though the children in Ramel El Zarif school depicted the war through the hitting their houses in the very first days of their displacement, with time the drawings have changed to tanks, planes and warships which yet again were hitting houses.

In most of the drawings, it was Israeli war machines. Just one child drew a picture of the “shatyouka missiles” — meaning katyusha — of the resistance hitting back at the Israelis.

“Can I have the red pen?” a child would ask every few minutes. I did not pay attention to her at the beginning, but then the third time and after a complaint from another child about what she needed the red pen for, I wondered why is she sitting by herself in another corner of the school playground, and what is it she was drawing?

In response to the complaints of her fellow displaced children, she answered, “All the red pens are dried up and I cant finish my drawing!”

“What are you drawing?” I asked.

“The Palestinian flag,” she answered.

“Are you Palestinian?” I asked her.

“Yes,” she said, “I am from ‘Ain el Helweh (the Palestinian refugee camp in the south near Sidon). My name is Walaa and I am from Haifa in Palestine.”

“And your mother?” I asked.

“Still in ‘Ain el Helweh with my two brothers,” she said sadly.

“She can’t go back to them; the roads are full of holes, because the Israelis shot the roads,” Fatima, another child in the circle, volunteered to explain for Walaa.

When Walaa brought her drawing of the Palestinian flag to show to the other children after she was asked, one of the parents asked children to draw the Lebanese flags. Hadi, the child from Ya’ater, refused, saying, “I am with Brazil, not Lebanon! The Brazilian flag was still on the roof of our home when we left, I did not want to take it down after the World Cup was over; do you think it will be there when we go back?”

I wanted to tell Hadi, “Let’s hope you will be back,” but I could not. His home lies in the border and if the Israelis decide to have a buffer zone, who knows where Hadi will end up? Hadi was born in the southern part of Beirut, and “we moved back to our village after the liberation (of south Lebanon, when Hizbullah drove the IDF out in May 2005); we built a house and settled there. I myself never set foot in our village before the liberation of the south.”

“I wanted my children to grow up there; it is beautiful in the south,” Hadi’s mother says.

We who are volunteering at the shelter can say nothing.

“May god protect the resistance so we can return to our homes, inshallah,” Hadi’s mother says.

The war will end, whether in a week, a month, a year, or two years. No matter how it will end, Hadi, Ali, Zeyneb, Nour and all the children will live with these memories; their children will also know about it, as Walaa who never lived in Palestine, knows well.

The war will live on in them and they will always remember the brutality of Israel, and I am sure some will find a way to fight this injustice and shout out against it. Maybe then, the world will have been cured from its deafness and will listen to their stories and they will be able to return to their homes, not only in the south but also in Palestine.

Related Links

Mayssoun Sukarieh is a native of Beirut