The Electronic Intifada 12 January 2005

“A Time to Cast Stones”

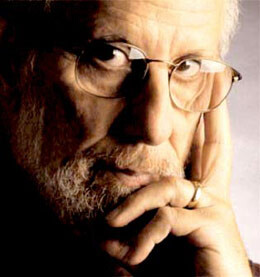

Born in 1930, Palestinian-American artist Rajie Cook has had a very successful career in graphic design. The “Symbol Signs” that hang in airports internationally, communicating purely through icons rather than text, were designed by Cook and his design firm. He has been honored by President Reagan and the “Symbols Signs” project has been acquired into the Smithsonian’s collection. However, Cook is not done creating work that intends to communicate. Born in the United States to parents originally from Palestine, the violence and continued injustice that consume his homeland spurs him to make Joseph Cornell-inspired boxes that comment upon various aspects of the conflict. In this interview with EI’s Arts, Music, and Culture Editor Maureen Clare Murphy, Cook explains his work:

Rajie Cook

RC:My father Najeeb Esa Cook was born in Jerusalem, Palestine on March 23, 1886. He was one of the very early immigrants to America making several trips, his first in 1906 at age 20. He married Jaleela Totah in Ramallah on April 20, 1920. They arrived in the USA in 1927, living in Newark and then Bloomfield, NJ. My father was a peddler selling fine linens, draperies and bedspreads in New Jersey. They raised their family of 5 children, Lillian, Rajie, Julia, Wade and Edward. In the early ’40s, after several unsuccessful cataract operations, my father lost his eyesight. He never saw any of my work as a graphic designer and obviously the art that I am currently doing. Living to age 94, Najeeb enjoyed his growing family of 10 grandchildren. My mother died in 1992 at the age of 89. I really never asked my father why he left Palestine, but I would imagine it was for the opportunities that were possible for him in America.

EI:On the front page of your website, you write that your fourth grade teacher suggested you go by the name of Roger, rather than your given name “Rajie.” You write that “Rajie,” which means “hope,” is now back. Can this be interpreted that you have reconnected with your Palestinian heritage, by making artwork that responds to what is happening in Palestine? And have your travels to the region precipitated this reconnection?

RC:I have never felt disconnected from my Palestinian heritage. I was always proud of who I was and where my roots were. Travel to the region has indeed increased my need to create public awareness of the details of the Palestinian struggle. This “connecting” goes back to 1948. I remember being glued to the TV in the ’50s, when then president Eisenhower forced England, France and Israel to cease their offensive activities in Egypt. Also during ‘56, ‘67, ‘73 and ‘82 I had a difficult time focusing on anything other than what was happening in the Middle East. In 1981, after spending a month in the Middle East, I started writing letters to my congressmen and senators. I sent over 50 letters and received form responses that always included, “Israel was the only democracy in the Middle East.” In the mid ’80s I was asked to serve on the Presbyterian Church’s Task Force on the Middle East, which I did for 10 years. After several trips to the Middle East, sponsored by the Presbyterian Church USA, visiting the West Bank, Jordan and Israel, and one trip to Syria, I began writing letters to my local newspapers and also meeting with two of my congressman. While on one of the fact-finding trips with the Task Force I decided that my efforts as an activist might become more effective by applying my experience and talent as a graphic designer. I started designing and producing posters. I remember, while studying at the Pratt Institute and later during my career as a graphic designer, I enjoyed creating assemblages and visual (sometimes mirthless) puns similar to the pieces “Whatsoever Ye Saweth” and “Justice Suspended.”

“Whatsoever Ye Saweth”

“Justice Suspended”

EI:I’m curious to hear at which point in time you began making boxes. It seems that the subject matter of the boxes have changed with the current Palestinian intifada, and that they have become more explicitly political, directly referencing the Palestinian struggle. Have you always produced artwork that discusses Palestine?

RC:I enjoy working with my hands and always liked working with wood and tools. Sometime in 1999, combining my experience as a designer/photographer/woodworker, I began making these boxes. Yes, my work has become more explicitly political and focused on the Palestinian struggle. An expression of frustration … I guess you can say these boxes are my “rocks.” Much of my life (over 50 years) as a graphic designer has been spent designing all forms of corporate communications: annual reports, brochures, posters, logos, and trademarks. My first involvement in creating visual art dealing with Palestine was in the early ’90s with posters, and in 1999 I began [the exhibition] Thinking Inside The Box. Communicating visually was much easier and more natural for me than using the written or spoken word. So expressing myself by creating these little “theaters” that relate to the injustice that is taking place in the Middle East was easier for me than verbally debating the subject with someone. And it’s somewhat more difficult for any “someone” to argue with a box.

EI:Looking at the Exhibitions page on your website, it appears as though you have mostly shown your work in shows revolving around the theme of Palestine. Have you had difficulty exhibiting your work in less geographically specifically themed shows?

RC:Here in America, with very few exceptions, artists whose work expresses the struggle of the Palestinian people will most always have a problem exhibiting their work in museums. Yes, I have been turned down many times - and almost always without an explanation. Of the fifteen exhibits that I’ve been in since exhibiting my boxes in my first show in March 2002, only three exhibits were less geographically specifically themed shows. All three were solo shows. One of the three was a museum exhibition, the other two were at private schools.

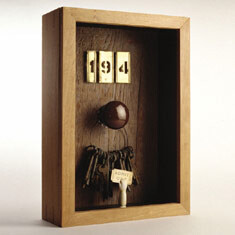

“Hope on Hold”

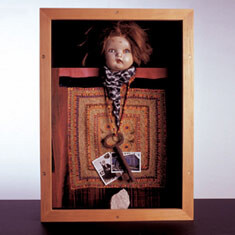

“Home Sweet Home”

EI:I’m wondering if the average American art viewer will be able to pick up on some of the references in your work. Like 2000’s “Hope on Hold,” which features metal stencils with the numbers 194, for UN Resolution 194, above a doorknob adorned with keys and a toy hand holding a ticket that says “admit one.” How important is it to you that people know that Resolution 194 reads that refugees should be allowed to their homes as soon as possible, and that it was drafted in response to the hundreds of thousands of Palestinians displaced during the establishment of Israel in 1948?

RC:In a museum show at the Cape Cod Museum of Fine Arts in Massachusetts I briefed about fifteen museum docents on the message of the boxes. At the two exhibits that I had in the private school I had an opportunity to lecture to the students. In several of my shows I have placed a poem by Nathalie Handal adjacent to my work, to help the average American art-viewer get the message. I’m not sure it’s the best way. I think it’s very important that the viewer get the message.

EI:In “Home Sweet Home” (2003), the box contains a doll’s head wearing a keffiyeh and a key around her neck. The key stands in front of vintage pictures and a traditional panel of embroidery. Do you consider Palestine your home? Also, there is a stone at the bottom of the box. Is this to remind the viewer that the current intifada, where Palestinians are fighting largely with stones, is still a battle over the continued injustices Palestinians have suffered since the establishment of Israel?

RC:In “Home Sweet Home” the traditional panel of embroidery is a photograph I took of my mother’s dress. One of the two vintage photographs is of the home my father built in Ramallah in the 1920s. The other is a photo of my grandfather. While living with two names, Rajie/Roger, I feel that I am also living with two homes. That feeling is in my blood. The stone is a powerful symbol of the imbalance of state nuclear power against the stone. I’ve used it both in posters and in my boxes, and you have done a good job expressing my reason for its use.

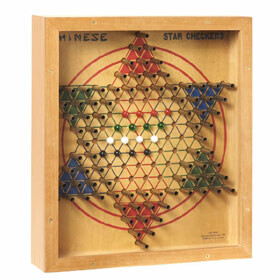

“Checkpoint Checkers”

RC:I have always had a difficult time discarding things. For example, I still have a lot of my train tickets from the seventeen years of commuting to NYC from PA, starting in 1967. I’ll most likely use some of them in a box. I even still have my driver’s license from 1947 and my Boy Scouts membership cards, and I used them in the bio section of my website. I am an avid collector. I collect vintage toys, clocks, tools, posters, etc. I spend a lot of time in antique shops and flea markets, looking for “things” that might help express symbolically the message I want to communicate in my art. But first, the very box that I construct represents the oppressive, restrictive occupation within which the Palestinian people now exist.

EI:The pieces that resonated the most with me were, strangely enough, the ones that didn’t explicitly refer to Palestine with the use of a keffiyeh, a flag, or language like some of your other works. I am particularly struck by “Future Bound,” in which a weathered metal bird stands with rope around its neck, atop a series of smaller boxes containing eggs bound by rope, and “Justice Suspended,” in which a judge’s gavel is suspended by wooden rods. Do you have much of an idea of which works in particular resonate with your audience? Is it these pieces, which have a more universal message, but equally as relevant to what’s happening with the Palestinians, or is it the work that is more specific in its subject matter?

RC:Most people respond as you did to the two boxes you mentioned. They’re easy to comprehend. There are no unfamiliar icons in these boxes. These two pieces, along with the saw, hammer and drill, have a more universal message and could fit many situations similar to that now being experienced by the Palestinians.

EI:Lastly, if a just answer is found to the question of Palestine in your lifetime, do you think you will continue to make boxes? Or might your work be more free-form, and not bound to small spaces?

RC:I think I will continue making boxes. Some of my more recent boxes include a kinetic “fourth dimension” - as you approach the box a sensor activates mechanisms that go into action. “Jenin Jenin,” “Homage to Joseph” and two others that you have not seen also include kinetics: lights, motion, perhaps sound. One of the pieces, “Shock and Awe” reflects the handling of prisoners in Iraq.

Related links:

Currently living and working in Ramallah, Maureen Clare Murphy is Arts, Music & Culture Editor for EI.