The Electronic Intifada 29 November 2012

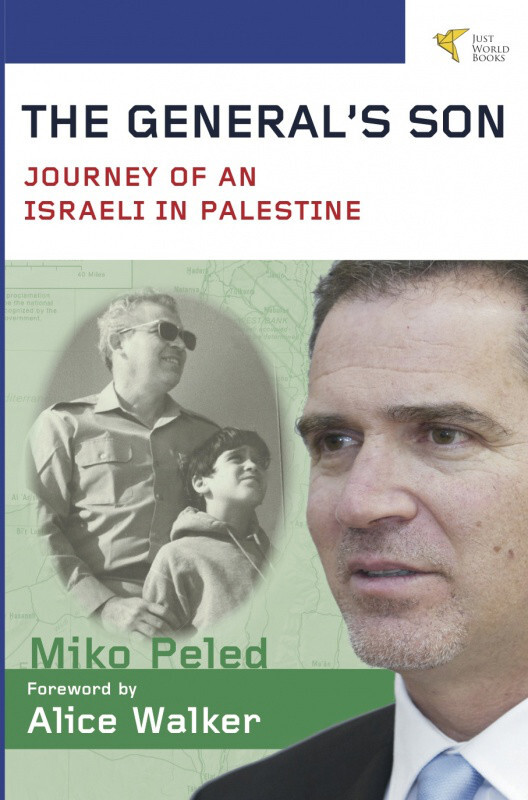

My review of The General’s Son, by Miko Peled, cannot be separated from what I’ve come to know about the author. After all, this book is about Peled’s own life, and his journey to a new understanding of the conflict that has defined so many of our lives. It is a narrative of the author’s transformation from an ardent Zionist, born into a revered military Israeli family, to a human rights activist and advocate of a single binational state.

In addition to reading this book, I attended one of Peled’s lectures and watched another online, and I’ve had a chance to speak with him in person and at some length. At each of these junctures, my reaction to his narrative changed to some degree.

I first picked up this book when I was asked to conduct a live interview with the author in New York. The initial parts, although told from the vantage of reflection, are replete with Zionist myths and verbiage spanning the full spectrum of hard-line Zionism to Zionism-light. Although Peled has made it clear in his lectures that he rejects Zionism, there is equivocation on this point in The General’s Son.

This is perhaps not surprising since he wrote the book over an extended period of time in which Peled was undergoing a process that unhinged fundamental assumptions about his own identity. But this means that the reader is left with phrases like “revival of Jewish national homeland” (26), “his generation fought so hard so that ours could live in a democracy” (58), “heroic missions” (105), and “my people fought so hard to win it back” (119).

More than 100 pages into the book, I was annoyed enough to beg out of my commitment to interview Peled because, as I told his publisher, I didn’t think I was the best person to interview her client if she was looking for me to be a promoter of his book. The publisher suggested I read on. She thought I would change my mind by the end of the book. I agreed, and to some extent my attitude softened, but not to the extent she promised. It was not until the last few pages of the book, when I found the single sentence I had been waiting to read (without realizing that I had been waiting for it), that I felt open to meeting the author. I’ll get to that.

Father of peace?

Peled gives us a personal glimpse of a man that many of us Palestinians could not figure out whether to love or hate. It is clear that many Palestinians loved Matti Peled, Miko’s father, the Israeli general who was one of the chief architects of our ethnic cleansing. Matti Peled was a Zionist who later became an Arabist and actively worked to restore the rights of persecuted Palestinian individuals. In fact, many notable Palestinians referred to him as “Abu Salam” (Father of Peace), although we are told that his motivation mostly stemmed from a desire to “preserve” the moral fabric of Israeli society.

Miko understandably treats his father’s memory with reverence and highlights the man who actively sought peace and co-existence, rather than the war-maker. He presents the reader with the general who was well ahead of his time, one of the earliest advocates of the two-state solution, a prescient man with eerily accurate predictions of popular Palestinian resistance that would turn Israel into a brutal and despised occupier.

The younger Peled tells us of the general who reached out to the PLO (Palestine Liberation Organization) when his country wouldn’t and who formed a sincere friendship with Issam Sartawi, a senior member of the PLO. All of that is true, but there are holes, too, in this projection. For example, Miko tells us that his father wrote an article lamenting the loss of Ariel Sharon’s “military genius” when the latter was not appointed chief of staff (117).

Matti Peled wrote that Sharon “combined the unique quality of being a brilliant military man, an admired leader and he knew how to organize his command so as to achieve the best possible results on the battlefield.” This article was written in 1973, long after Sharon’s brutal exploits became well known. After all, Ariel Sharon’s massacre in the village of Qibya in 1953 provoked an international outcry, and surely Matti Peled was already well-acquainted with Sharon’s form of “military genius.”

It is clear, however, that the general had a change of heart, not quite to the extent that his son would many years later, but a significant change nonetheless. Interestingly, this does not seem to have been passed on to his children in his lifetime, at least not to his son, Miko. In fact, the author tells us very little about his relationship with his father and one gets the impression that the general was a remote father, impatient with his family, and too absorbed in the affairs of the state to indulge the predilections of the heart.

Thus, the anti-Arab racism suffused in Israeli textbooks and codified in the social milieu went unchallenged in Miko’s life until he was an adult mourning for his niece, Smadar, who was killed by a suicide bomber not much older than she.

Remarkable journey

To the reporters gathered at her home, Smadar’s mother (Miko’s sister), professor Nurit Peled-Elhanan, blamed the Israeli government’s “megalomania” for her daughter’s death and the death of the suicide bombers. Although she is mentioned infrequently in Miko’s narrative, Nurit emerges from the pages as a woman of great strength and moral fortitude, and a mother in the truest sense.

Miko’s attempt to understand his sister’s reaction pushes him to reach out to Palestinians in his own town of San Diego, California. His first step was a Palestinian/Jewish-American dialogue group, and he took it with no small measure of fear. In fact, both he and his wife were afraid for his life to be in the home of a middle class Palestinian family in suburbia, USA. And when he was there, his wife called a few times to make sure he was okay.

I do appreciate the author’s honesty and respect his willingness to unveil such racist attitudes, but I admit, reading this part reminded me of the white woman who tenses her body and clutches her purse at the sight of a Black man, sure that the man’s only thought is how to rape and rob her. But Peled pushed through that ignorance and pulled his family with him to a sense of brotherhood, even deference, toward Palestinians. That’s a remarkable journey.

It is inspiring and enlightening to read the unfolding of one man’s path to liberate himself from racist ideologies, to disavow the privilege accorded to him because it comes at the expense of those who do not belong to his religion. I imagine it cannot be an easy path.

The critical eye can discern some stumbles in this journey and recognize certain “baby steps” the author takes to internalize the truth. One such example occurs when Miko is confronted by a Palestinian narrative diametrically opposed to what he has known his whole life. He then learns that objective, recorded historical fact supports the Palestinian narrative, not his. So he writes the following: “The willingness to accept another’s truth is a huge step to take. It is such a powerful gesture, in fact, that contemplating it can make you want to throw up.”

In reality, however, it is not so difficult to accept the truth of other human beings when we seek to understand. The truly difficult part, I imagine — the part that makes you want to throw up, perhaps — is the willingness to accept that what you’ve believed your whole life is, in fact, a lie. That is the personal triumph that Miko Peled clearly achieved. He dismantled a lifetime of racist assumptions and replaced them with something more human and tender.

Turning point

Miko Peled was born in Jerusalem and grew up believing the Holy Land was his rightful ancient homeland. He believed that his own personal lineage extended thousands of years in Jerusalem, even though he was clearly aware that his grandparents arrived in Palestine from Eastern Europe. In describing the friendships he forges with various Palestinian individuals, he speaks of being “sons of the same homeland” and creates a parity with regard to the depth of their roots in that land.

Peled aligns his sense of belonging on a par with that of Palestinians and speaks about recent Israeli settlers with disdain, often referring to their heavy “Russian accent” to emphasize that they are foreigners. Peled says, “I couldn’t help but think it ironic that these new immigrants, who could barely speak Hebrew, had rights over these lands that the Palestinians were denied simply because they were Jewish. Quite unbelievable!” (143).

And when his Palestinian friend Nader el Banna tries to visit his homeland but is detained by one such young Israeli newcomer in a soldier’s uniform, Peled was indignant, saying, “It takes a special kind of arrogance or ignorance, for someone who is new to a country to keep an older person (who was born in that country and whose ancestors were born in that country) out” (150).

He’s right, of course, but he falls short of acknowledging that, in fact, his father’s generation stood precisely in that arrogant and ignorant space and people like my grandfather sat defenseless in Nader el Banna’s place.

In getting to know Miko Peled, I think he understands this, but that that understanding doesn’t come through in the narrative. This attitude extends to land and settlements. On pages 143 and 216, for example, he writes, “these settlements are not going away, I thought, and this land will never be handed back to its rightful owners,” and “having witnessed Israel’s immense investment in infrastructure to attract Jewish settlers and thereby exclude Palestinians — to whom the land belongs.” Peled seems to apply this logic only to the West Bank and makes no reference to the rightful owners of properties in Haifa, for instance. This, to me, was a shortcoming in the book and the principle reason I remained suspicious throughout most of The General’s Son.

Then, with only three pages to go until the end of the book, I read Miko’s account of a conversation he had with his brother-in-law, who apparently still maintains that Israel should remain a Jewish state. Miko clearly disagreed and said: “But you know as well as I that we are all settlers, and all of Israel is occupied Palestine.”

That was the turning point for me. That was the sentence I needed to read, even though Miko didn’t elaborate beyond it.

Admitting the truth

It didn’t matter that Peled overcame a racist ideology. That’s his own personal journey of growth. Nor did it matter that he went so far past his fears that he befriended and came to love certain Palestinian individuals. It didn’t matter that he embarked on humanitarian projects to help. Or that he participated in protests that got him arrested by the Israeli occupation forces.

In the end, what truly mattered was setting the record straight and acknowledging that Palestinians are native sons and daughters who have been cruelly dispossessed of home, history, heritage and story. What mattered was the acknowledgement. Uttering the truth, no matter how painful, is what I needed to hear. Because it was in that admission that Miko Peled became a man I could embrace as a brother and fellow countryman.

In that sense, it can be said that this book is about how Miko Peled was transformed from being the general’s son to being a native son of the land.

Endearing and ugly

Much is packed into the few pages of this book. There are little known historic notes, like the fact that Israel’s taking of the West Bank, including Jerusalem and Gaza was a decision made during the 1967 War, not before it, by the generals, not the civil government. It contains endearing and funny moments. I found it wonderful that Miko’s commanding officer called him the “antithesis of a soldier” because he was too left-leaning.

The reader learns that Benjamin Netanyahu and Miko’s sister Nurit had been like “brother and sister.” That’s hard for me to imagine. But when they run into Netanyahu in Jerusalem, Miko’s son later asks why “that man” had so many bodyguards. Nurit is quick with the delightful reply that “he must have done something really terrible and now he’s afraid for his life.”

There are touching sections of the book where Miko speaks of Palestinian children whom he trains in a karate studio (Miko is a 6th degree black belt). They are tender and endearing and truly lovely. On the opposite end of this spectrum, Peled also describes conversations he had with Israelis in Japan and one gets a sense of how Israelis speak to each other when they think no one is listening. The account of this is sickening, and Miko himself relates wanting to throw up afterward.

My criticisms aside, this is an important book, full of hope and inspiration for a shared destiny between Palestinians and Israelis based on mutual respect and equal rights. I recommend it. And I think Miko Peled is an important new voice, from which I hope to read and hear more.

Susan Abulhawa is the author of the international bestseller Mornings in Jenin and founder of Playgrounds for Palestine.

Comments

The General's Son

Permalink Antoine Raffoul replied on

I bought the book after listening (online) to a Miko Peled's lecture. I am always careful not to shower one with praise for having rejected a previously held dubious belief. After all, he had simply found the right belief. Firstly, I am bothered by the book's title: "The General's Son". I sense that the emphasis here is not on the 'son', 'the father' or their relationship, but on the word 'the General'. No offence intended here, but the military qualifications in modern day Israel do top the qualities of a serving person. It has been said that the Israeli army has a State, not that the State has an Israeli army.

As soon as I started reading the book, I was showered with phrases like [my father] "had fought fiercely in Israel's War for Idependence" (14). Miko, as a boy, saw "military legends" pass through his family home (15). Even as early as page 36 and I have picked up more phrases which seem like stumbling blocks along the way to completing this book. Maybe, I will end up sympathising with Susan Abulhawa's conclusion by the time I finish the book. However, it seems like an uphill struggle now, unlike the ease I felt listening to Miko Peled's lecture.

I would guess that the book was written for all audiences (including Israeli ones) while the lecture was for a specific one in a sheltered zone.

miko peled

Permalink John El-Amin replied on

Dear Ms. Abulhawa AsSalaamAlaikum

The struggle for justice for the Palestinian people needs voices, unqualified and unconditionally advocating a renunciation of Zionism and a re-possession of stolen land, in addition to compensation for damages inflicted.

I have not yet read the book and your recommendation may inspire me to do so.

Afrikaners and Southern whites, in many instances feel no obligation to right their wrongs. I feel that only the Palestinian people can determine justice and certainly not Americans in government.

My views may be skewed as the established pattern of horror is and has been approved by present and past US leaders.

Does Mr Peled condemn US/ Israeli American complicity in this history of atrocity?

I will read this book and continue to loudly speak out and support Palestinian justice.

The General's Son

Permalink Larry Snider replied on

Susan,

I have found in my reading that I have judged the value of authors based on their place on a continuum of war and peace/hate and love and for many years gave those who touched the pain of Palestinian history a pass and those who struggled with their own history and feelings less room to express their own pain. Over time I find I continue to recalibrate the continuum recognizing that for some considering two states is as far as they may be able to go even as others can do the hard work like that done by Miko Peled to more fully face truths and transform themselves. I have become less sure of myself and others even as I continue to work to open hearts and minds including my own.

An excellent review

Permalink Jeff Blankfort replied on

I have just finished reading Miko Peled's book and found myself agreeing with virtually every point as she progressed to the book's end in which Peled clearly comes to understand that there is no longer a place within his mindset for the lies that justified the establishment of Israel. I had the advantage in happening to know his father, the general, who was far more radical in private than he was in public where, in San Francisco, in 1983 when I met him, he was openly calling for an end to US aid to Israel, something the Palestinian solidarity movement had yet to do. Later that year, before going to Israeli-occupied Lebanon, I visited him at his home outside of Jerusalem where his comments about what was then the Israeli "peace movement," much hailed by certain American political activists, were unreservedly critical and for all the right reasons. In short, he had no use for it.

Almost without exception, most Israeli generals and high ranking officers, upon their retirement either go into mainstream politics, accept a position as the head of a profitable arms manufacturer, or become involved in a shady firm providing "security" to one or more dictators around the globe.

Ex-General Peled was that exception.Getting to know more about him and how he, foreshadowing Miko, came to re-evaluate what he and others had done to Palestine and to the Palestinians was one of the more fascinating aspects of the book.

It should be said that Miko has taken positions far more radical than any of the domestic Jewish peace groups and, speaking in Berkeley, called for the boycott, divestment, and sanctions campaign not to be limited to the West Bank but to all of Israel since, realistically, they can't be separated, something the American BDS movement has yet to do.