The Electronic Intifada 20 November 2012

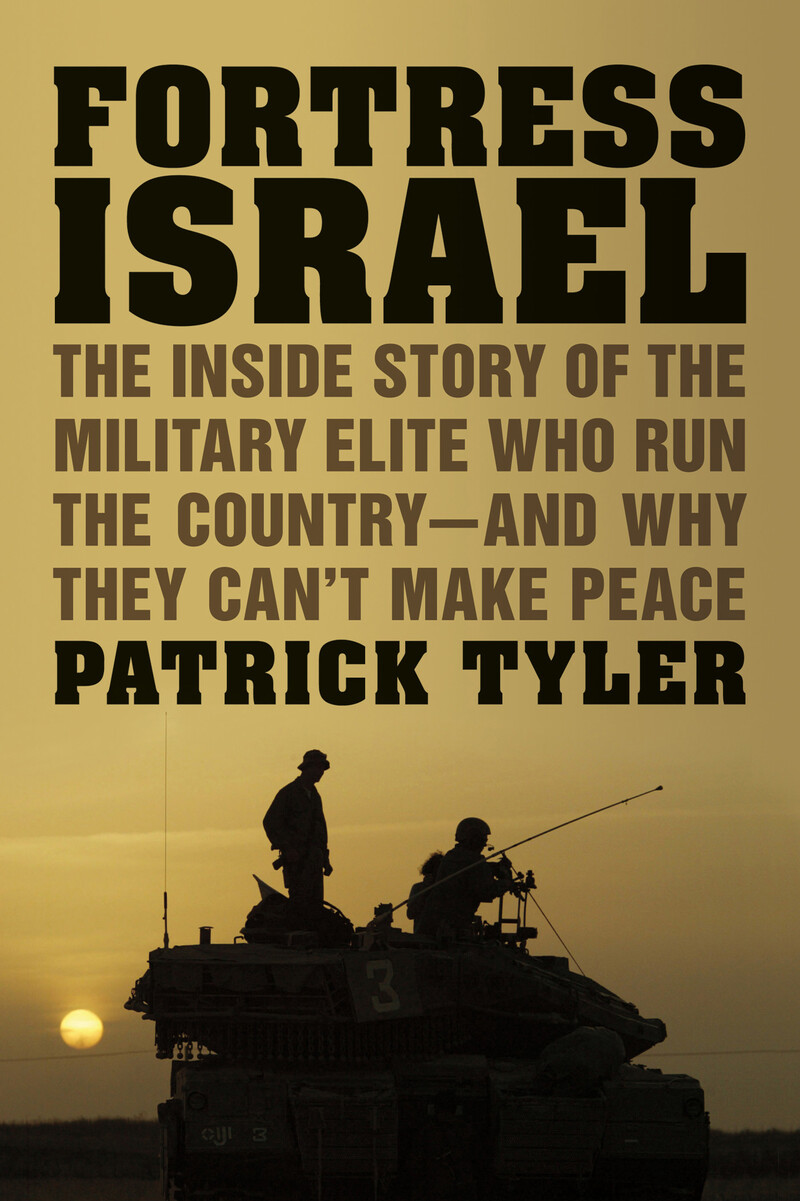

Fortress Israel: The Inside Story of the Military Elite Who Run the Country — And Why They Can’t Make Peace by former New York Times and Washington Post reporter Patrick Tyler is an unflinching history of the role of militarism in Israeli society. Tyler previously wrote A World of Trouble: The White House and the Middle East — from the Cold War to the War on Terror (2009), which examined how US presidents from Dwight Eisenhower to George W. Bush responded to events in the Middle East.

In this new work Tyler narrows his focus to the Israeli establishment. He sums up his thesis in the prologue: “Israel, six decades after its founding, remains a nation in thrall to an original martial impulse, the depth of which has given rise to succeeding generations of leaders who are stunted in their capacity to wield or sustain diplomacy as a rival to military strategy, who seem ever on the hair trigger in dealing with their regional rivals, and whose contingency planners embrace worst-case scenarios that often exaggerate complex or ambiguous developments as threats to national existence. They do so, reflexively and instinctively, in order to perpetuate a system of governance where national policy is dominated by the military.”

In Fortress Israel, Tyler mines a trove of US government documents declassified in 2007, many of which were obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests by the National Security Archive at George Washington University, where Tyler is a fellow.

These documents, especially those from the administration of Richard Nixon, have received scant attention from the corporate media. Tyler also relies on interviews he conducted with many Israeli leaders, as well as secondary sources — the most prominent of which is The Iron Wall (2000), a book by the Israeli historian Avi Shlaim.

Both The Iron Wall and Fortress Israel demolish key pillars of Israel’s long-standing propaganda effort to portray itself as the perpetual victim of surrounding, hostile Arab nations. They show instead that Israel was the aggressor in nearly all of its military conflicts.

The 1956 Suez Crisis, for example, resulted from a conspiracy hatched by France, Britain, and Israel in which Israel attacked Egyptian forces so that Britain and France could pretend to intervene as “stabilizing” forces and thereby maintain control of the Suez Canal. Similarly, both studies reveal that Israel launched the 1967 war not because it believed Egypt was about to attack but because it saw an unprecedented opportunity to destroy the Egyptian army.

Imperial interests

Tyler’s research demonstrates that the Israeli elites long ago recognized the usefulness of aligning Israel with Western imperialist interests in the Middle East and openly courted the US on that basis. Although the Eisenhower administration forced the withdrawal of Britain, France and Israel from Egypt in 1956, angered that all three countries acted without its support, it soon realized that Israel represented a valuable Cold War ally — especially as Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser tilted toward the Soviet Union.

But Tyler argues that whereas the Eisenhower administration acted to restrain Israel “so that it might find accommodation with its neighbors,” the Nixon administration, especially National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, sought to use Israel to achieve US interests in the Cold War.

Drawing on the 2007 documents, Tyler quotes from a 1969 memo to Nixon from Richard Helms, then director of the Central Intelligence Agency, saying Israeli aggression against Egypt should be encouraged “since it benefits the West as well as Israel.” A cover note by Kissinger argued that if Nasser were toppled, any successor would lack his “charisma.”

“Hit ‘em hard”

An Israeli bombing campaign against targets deep inside Egypt followed in January 1970. In May that year Nixon told Israeli foreign minister Abba Eban and Yitzhak Rabin, then the Israeli ambassador to the US, to “let ‘em have it! Hit ‘em as hard as you can!” One of those hits had already included an Egyptian elementary school, killing 47 children.

During this same period, Tyler notes, US officials became aware that Israel was a nuclear weapons power, after years of Israeli denials. Kissinger had just received a CIA estimate that Israel possessed at least ten nuclear weapons. According to a Kissinger memo, Rabin told him there were two reasons for developing the bomb: “’first to deter the Arabs from striking Israel, and second, if deterrence fails and Israel were about to be overrun, to destroy the Arabs in a nuclear Armageddon.’”

Israel’s acquisition of nuclear weapons — along with the peace accord it subsequently reached with Egyptian president Anwar Sadat — established Israel as a regional superpower, Tyler notes, adding that Israel reluctantly agreed to recognize Palestinian national rights as part of that accord. At the same time, he writes, the Israeli military establishment was determined to remain independent of the great powers and never allow them “to become the arbiters of peace.”

Nakba overlooked

Tyler demonstrates convincingly that the Israeli military often either ignored or overrode civilian authority. Although numerous examples support his thesis that the military is the dominant force in Israeli politics, he provides insufficient evidence to indicate that there were ever any substantive strategic differences between Israel’s civilian and military leaders in relation to the ongoing ethnic cleansing of the Palestinians. He overemphasizes the “sabra [native born] culture” within the military as the wellspring of Israeli militarism, failing to note that Israel’s civilian leaders, even though many were not sabras, nevertheless were strategically aligned with Israel’s principal military ambition — to erase Palestine from the map.

But perhaps the book’s most significant failing is that it ignores the Nakba (catastrophe), the systematic ethnic cleansing that led to Israel’s foundation in 1948. This omission tends to frame the narrative as simply an ethnic conflict among nation-states rather than a conflict between a Palestinian national liberation struggle and a racist settler-colonial state.

To his credit, Tyler ultimately does address the core issue — the suppression of Palestinian national rights. He suggests Israel’s military elites may be determined to keep Palestinians permanently subjugated under occupation. However, his one-sided focus on the military obscures the role of Zionist ideology and its grip on both civilian and military elites.

Even the two-state solution favored by “liberal” Zionists anticipates the ongoing second-class status of Palestinians in Israel and the denial of refugees’ right of return. Ultimately, this is why the Israeli elites cannot make peace. Instead of envisioning a peace based on human rights, they can only propose a “peace” based on violence.

Rod Such is a freelance writer and former editor for World Book and Encarta encyclopedias. He is a member of the Seattle Mideast Awareness Campaign and Americans United for Palestinian Human Rights.

Comments

Fortress Israel mind-set

Permalink Truth seek replied on

Pray for the insane Israeli military elites, as hard as you pray for countless hundreds of thousands of victims of their insanity. There is the hope that, on the day before The Day of The Final Judgement, they will realize they are not - and never will be - the rulers of the universe. Thus, repentance for their crimes remains a possibility for them. And a reversal of the escalating insanity, which they have inflicted upon the world since 1948, remains a possibility for the non-Zionist world - which includes countless, decent Jewish citizens everywhere.

Thank you!

Permalink Magdalena replied on

Thank you for your comment! I fully share what you have expressed! My heart is bleeding for Palestine and specially for Gaza. I just can't find words for what is happening now - and happened since 1948 and 1967! I am with my Palestinian friends.

With love,

Magdalena

let's have constructive rhetoric

Permalink Balensen replied on

Painting the Israelis/Sabras as cartoonish villains is hardly constructive. The Sabras were not bloodthirsty lunatics, they just had retrograde ideas about settling a land already occupied by another people and it seemed to them a good idea at the time. When the Arabs decided to show the Sabras they had made a mistake by military force and threats of annihalation, the Sabras understandably became a martial society for fear of being annihalated, but this is not irreveocable.

IMHO, just as the Israeli military elite was created by the Arab threat, so too can it eventually be unseated by peaceful overtures and diplomacy.