B'Tselem 26 August 2005

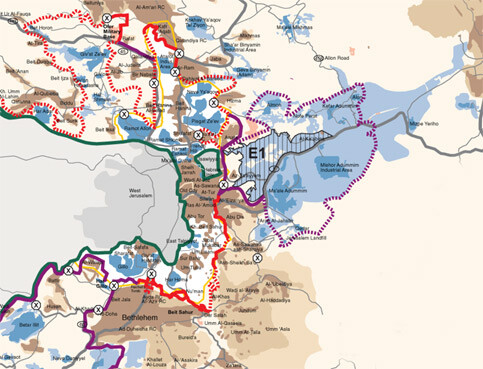

The Separation Barrier - Jerusalem Area, May 2005 (B’Tselem)

The government’s plan calls for the separation barrier to surround East Jerusalem and detach it from the rest of the West Bank. The relevant decisions and approvals to begin construction were made in three principal stages:

In June 2002, as part of the decision in principle to build the whole separation barrier, the government approved Stage A, which included two sections north and south of Jerusalem. The northern section extends for some ten kilometers, from the Ofer army base on the west to the Qalandiya checkpoint on the east. The southern section, also about ten kilometers in length, runs from the Tunnels Road on the west to Beit Sahur (south of Har Homa) on the east. The two sections were completed in July 2003.

In September 2003, the Political-Security Cabinet approved the barrier’s route in the other areas around Jerusalem, except for the section near the Ma’aleh Adumim settlement. These approvals were made in the framework of construction of Stages 3 and 4 of the entire barrier. The approval related to three subsections. One section is seventeen kilometers long, extending from the eastern edge of Beit Sahur on the south to the eastern edge of al-‘Eizariya on the north. The other section covers a distance of fourteen kilometers, from the southern edge of ‘Anata to the Qalandiya checkpoint on the north. The third section is also fourteen kilometers, and surrounds five villages northwest of Jerusalem (Bir-Nabala, al-Judeireh, al-Jib, Beit Hanina al-Balad, and Nebi Samuel), which are situated bear the city’s municipal border. Most of the barrier in these sections will be a wall. The progress in building these sections varies: some parts have been completed, while in others, work has not begun.

In February 2005, the Israeli government approved an entirely new route for the barrier following the High Court of Justice’s decision in June 2004 that voided a section of the barrier on the grounds that it disproportionately harmed Palestinians in the area. The amended route made significant changes in various areas, but in the Jerusalem area the route largely remained as it was, except for an addition of forty kilometers that will surround the Ma’aleh Adumim settlement and settlements near it (Kfar Adumim, Anatot, Nofei Prat, and Qedar). However, the government did not approve commencement of work on this section, and conditioned confirmation on the “further legal approval”.

The dominant principle in setting the route in the Jerusalem area is to run the route along the city’s municipal border. In 1967, Israel annexed into Jerusalem substantial parts of the West Bank, a total of some 70,000 dunams [17,500 acres]. Some 220,000 Palestinians now live in these annexed areas. There are two sections in which the barrier does not run along the municipal border: in the Kufr ‘Abeq neighborhood and in the area of the Shu’afat refugee camp, which are separated from the rest of the city by the barrier, even though they lie within the city’s jurisdictional area.

Palestinian towns and villages (Ramallah and Bethlehem, for example) are situated not far from Jerusalem’s border. These communities are home to hundreds of thousands of Palestinians who have ties with Jerusalem. These ties with Jerusalem are especially close for residents of communities situated east of the city: a-Ram, Dahiyat al-Barid, Hizma, ‘Anata, al-‘Eizariya, Abu Dis, Sawahreh a-Sharqiya, and a-Sheikh Sa’ad (hereafter: “the suburbs”). The suburbs, with a population in excess of 100,000, are contiguous with the built-up area of neighborhoods inside Jerusalem. Until recently, the city’s border had an inconsequential effect on the daily lives of the residents on both sides of the border. Residents of the suburbs who carry Palestinian identity cards officially need permits to enter East Jerusalem, but many routinely enter without a permit. Running the barrier along the municipal border completely ignores the fabric of life that has been evolved over the years, and threatens to destroy it altogether:

In light of the housing shortage in East Jerusalem, over the years, tens of thousands of residents of East Jerusalem moved to the suburbs. They still hold Israeli identity cards and receive many services in the city.

Thousands of children living in the suburbs study in schools in East Jerusalem, and many children living in Jerusalem study in schools outside the city. Similar reciprocal relations, albeit on a lesser scale, occur in higher education.

The suburbs do not have a single hospital. Most of the residents use hospitals and clinics in East Jerusalem. Women from the suburbs almost always give birth in Jerusalem hospitals because they would have to cross a staffed checkpoint (the “container” checkpoint and the Qalandiya checkpoint, respectively) to get to hospitals in Bethlehem and Ramallah, which may entail long delays.

A large proportion of the workforce in the suburbs is employed in Jerusalem, East and West. Shops, businesses, and factories in the suburbs rely on customers coming from Jerusalem. Many businesses have closed since construction on the barrier began.

Residents of East Jerusalem have close family and social relations with residents of the West Bank, and with residents of the nearby communities in particular.

Israel contends that gates in the barriers will enable residents to cross from one side to the other and to maintain the existing fabric of life. However, experience regarding the operation of the gates in the northern West Bank section of the barrier raises grave doubts about the ability of the gates to provide a workable solution: crossing through the gate requires a permit, and many persons wanting to cross are listed as “prevented” for varied reasons; most of the gates are open only a few hours a day, far less than is needed to meet the residents’ needs; residents must often wait a long time at the gates, sometimes because the gates do not open on time, and sometimes because of long lines

Israeli officials state at every occasion that two considerations were instrumental in choosing the route: maintaining security and obstructing Palestinian life as little as possible. However, using the municipal border as the primary basis for determining the route is inconsistent with these two considerations. On the one hand, the route leaves more than 200,000 Palestinians, who identify with the struggle of their people, on the “Israeli” side of the barrier; on the other hand, the route separates Palestinians and curtails the existing fabric of life on both sides of the barrier.

The decision to run the barrier along the municipal border, and the weak arguments given to explain that decision, lead to the conclusion that the primary consideration was political: the unwillingness of the government to pay the political price for choosing a route that will contradict the myth, that “unified Jerusalem is the eternal capital of Israel.”

B’Tselem believes that, in light of the way of life that has been created in large parts of the city since East Jerusalem was annexed by Israel in 1967, any security solution based on the unilateral construction of a physical barrier, including a barrier that runs along the Green Line, will severely violate human rights. Israel must meet its duty to protect its citizens and residents by other means, which respect the human rights of all persons living in territory under its control.

Related Links