The Electronic Intifada 3 February 2005

TWO GENERATIONS LATER, PALESTINIANS HAVE HOPES FOR THEIR LAND: IN THE MIDDLE EAST, MEMORY SERVES US

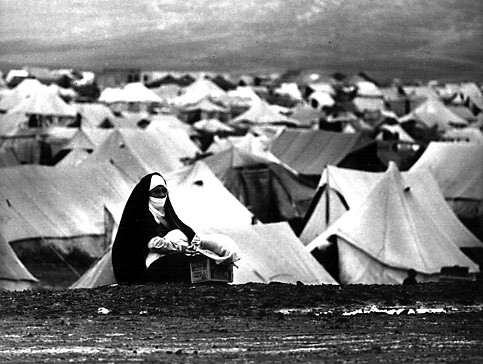

An older female refugee sits in Baqa’a Refugee Camp in Lebanon in this historical photo. (UNRWA)

Six decades ago, my family celebrated Christmas in its Jerusalem home, as did the families of other Palestinian Christians in Bethlehem, Nazareth and throughout the Holy Land.

Then, in 1948, Palestinian society was destroyed. More than 700,000 Palestinians — many, like us, Christians, but even more Muslims — fled or were forced into exile by Israeli troops. The Palestinians’ only fault was that they were not Jewish, and, by their presence and predominant ownership of the land, were obstacles to the creation of a Jewish state. Their exodus — called the nakba or “catastrophe” by Palestinians — was already nearly half- complete by May 1948, when Israel declared its independence and the Arab states entered the fray.

That is the history of the establishment of Israel that is often forgotten in the United States — but is stubbornly remembered by Palestinians.

Why do Palestinians who lost their homes, and who have been barred by Israel from returning ever since, remember their pre-exile lives with such enduring intensity?

What does it signify that this tradition of remembering has now been transmitted to generations of Palestinians who were born in exile, and have only known their old homes and villages from yellowed and crumbling photographs, like shadows left by a passing sun?

For me, my family, and for many Palestinians, this tradition of remembering is not a simple nostalgia for the past, or a longing for a period that can never be reproduced. It is a prescription for the future.

My paternal grandfather, Hanna Ibrahim Bisharat, built a home in the Talbiyeh quarter of Jerusalem in 1926. Although a Christian, my grandfather named his new home “Villa Harun ar-Rashid,” in honor of the celebrated Muslim caliph, renowned for his passion for justice, generosity and love of learning.

My family lived in the home for several years, during which several of my uncles were born, and one, as a toddler, died of pneumonia. His surviving twin still remembers watching the swirling heat waves rising from the kerosene heater, and wondering if that was his brother’s soul rising to heaven.

My father and his brothers played in the fields and orchards nearby, and went to school up the hill from the house at Terra Sancta College.

My grandfather had been educated in a Catholic school in Jerusalem, gaining fluency in English and French, to complement his native Arabic and Turkish. Eventually, he was sent, under the guidance of a Swiss clergyman, to Switzerland to study agricultural engineering. He returned home prior to the outbreak of World War I, brimming with naïve optimism, hoping to modernize local agriculture.

It was not to be, however, as radical changes ushered in by World War I were on the way. My family aided the British-led forces that swooped into Palestine from Egypt, once rescuing three soldiers lost behind Turkish lines and returning them to their own camp.

The Turks, learning of my family’s disloyalty, nearly executed all of them — showing mercy only after the intervention of a Bedouin sheikh who was indebted to the Bisharats.

In the early postwar period, my grandfather founded a business with a Muslim partner, providing food and other goods and services to the British Mandatory Government and purchasing army surplus goods and reselling them on the local market.

My uncles believe, in fact, that these transactions secured the financing for the family home in Talbiyeh, a virtually unsettled area consisting of olive orchards and vineyards.

My family’s relations with Jews during the pre-1948 period were entirely friendly. Jews were, like all others, simply members of Jerusalem society. During the 1929 riots that convulsed Palestine — in which 120 Jews and 87 Palestinian Arabs were killed — my family sheltered Jewish friends in Villa Harun ar-Rashid.

My father learned to love Western classical music in a listening group hosted by a young Jewish man. Palestinian Jews, Christians, and Muslims mingled at the YMCA, swam, and played basketball together.

My grandmother, introducing my American mother to the lentil and rice dish mujaddara, told her that it was the preferred wash-day meal for Muslims, Jews and Christians, due to its ease of preparation and heartiness.

Wash day was the first day after the Sabbath for each community, so aromas of mujaddara wafted through the neighborhood from Muslim kitchens each Saturday, from Jewish kitchens on Sunday and from Christian kitchens on Monday.

My family was not oblivious to the shifting political currents in Palestine. My grandfather, who had become prominent in Palestinian society, attended the deliberations at the United Nations over Resolution 181, the partition plan for Palestine in 1947.

While he had welcomed Jews in his home and country as equals, he opposed the creation of a Jewish state that would marginalize, if not exclude him, from his own land.

Our home in Jerusalem, like that of hundreds of thousands of other Palestinians, was taken over by Zionist military forces in 1948, and has remained in Israeli hands for 56 years.

I have written about this, and about my encounters with its Jewish inhabitants. I wrote as well about a very dear Jewish Israeli man, who once lived in our home, and who had the moral courage to step forward and meet with me personally to apologize for the taking of Villa Harun ar-Rashid.

I wrote about the potentially transformative power of apology, suggesting that an Israeli admission of responsibility for the exodus of Palestinians in 1948 would place relations between Israelis and Palestinians on an entirely new and hopeful footing. These writings appeared in English, and then in Israel in Hebrew.

Israeli reactions were alternately sobering and inspiring, ranging from crude racism and warnings to “Get ready for Nakba II” to heartfelt expressions of sympathy and respect.

A recurrent theme, however, even among the most compassionate, was the assertion that, in resolving issues between Palestinians and Israelis, “We cannot go back to the past,” and indeed, that we Palestinians must forget the past.

It struck me as ironic that such an admonition could issue from people whose claimed attachment to Palestine goes back 2,000 years. What this says is that who can remember, and who can be made to forget, is fundamentally an outgrowth, and an enactment, of power.

Viewed in this way, our remembering, is a form of continuing resistance to the defamation and erasure of our history.

But remembering Talbiyeh of the pre-1948 period is more than a form of resistance. Recalling that era, and the people it produced, involves envisioning a possibility for another future. Talbiyeh was a place of tolerance, compassion and enlightenment, its sons and daughters cosmopolitan, broadminded and welcoming.

In recalling and claiming this heritage, we are also promising that when Israelis are ready to recognize Palestinians in their full humanity, as no lesser beings than themselves, we will be there, in all our ingenuity, imagination, strength and, ultimately, even love.

To forget this rich legacy, then, is to deny our humanity, to negate our identity and to abandon a future in which Christians and Muslims are equal to Jews.

Recently, on the 10th birthday of my son, Austin Rashid, I was reaching for the telephone to order balloons for his party. I asked “What colors would you like?”

He paused from his latest Lego creation, and, looking at me squarely, replied, “Red, black, green and white.”

Stunned, I stared at him, not even aware that he knew the colors of the Palestinian flag. I searched the wells of his brown eyes for the impulse behind that startlingly adult request. He held my gaze for a minute, smiled and returned to his play.

And so each new generation remembers. That memory entails a future of equality, justice and peace for all the peoples of Israel/Palestine — and a time when Villa Harun ar-Rashid, and other homes there, will again be havens for all in need.

Related Links

George E. Bisharat is a professor of law at Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco and frequently writes on law and politics in the Middle East. This article was first published in the San Francisco Chronicle on 19 December 2004, and is reprinted with the author’s permission.