The Electronic Intifada 26 February 2009

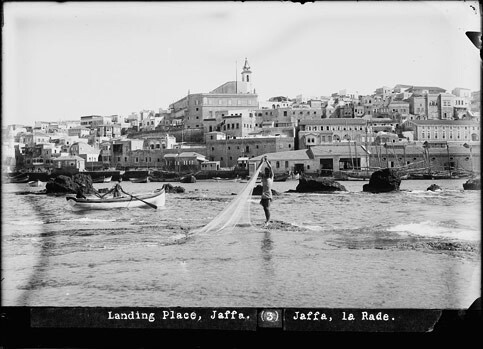

A view from the sea at Jaffa looking east onto the city, 1898-1914. (Matson Collection)

Jaffa was the largest city in historic Palestine during the years of the British mandate, with a population of more than 80,000 Palestinians in addition to the 40,000 persons living in the towns and villages in its immediate vicinity. In the period between the UN Partition resolution (UNGA 181) of 29 November 1947, and the declaration of the establishment of the State of Israel, Zionist military forces displaced 95 percent of Jaffa’s indigenous Arab Palestinian population. Jaffa’s refugees accounted for 15 percent of Palestinian refugees in that fateful year, and today they are dispersed across the globe, still banned from returning by the state responsible for their displacement.

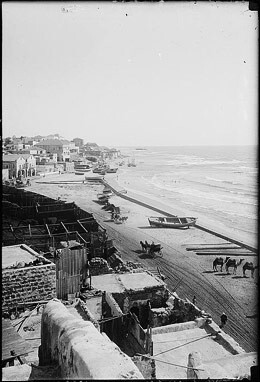

Jaffa was the epicenter of the Palestinian economy before the 1948 Nakba. Beginning in the early 19th century, the people of Jaffa had cultivated citrus groves, particularly oranges, on their land. International demand for Jaffa oranges propelled the city onto the world stage, earning the city an important place in the global economy. By the 1930s, Jaffa was exporting tens of millions of citrus crates to the rest of the world, which provided thousands of jobs for the people of the city and its environs, and linking them to the major commercial centers of the Mediterranean coast and the European continent.

With the success of its citrus exports, the city witnessed the emergence and growth of various related economic sectors, from banks to land and sea transportation enterprises to import and export firms, and many others. As the city grew, Jaffa’s entrepreneurs began to develop local industrial production with the opening of metal-work factories, and others producing glass, ice, cigarettes, textiles, sweets, transportation-related equipment, mineral and carbonated water, and various foodstuffs, among others.

In addition to commerce and industry, a third major pillar of Jaffa’s economy in the mandate years was tourism. Tens of thousands of tourists and pilgrims visited the historic city every year, both for its sites of historical and religious significance, its beautiful buildings, and the Christian holy sites scattered throughout the city. As Jaffa’s tourism industry grew, so too did its communications infrastructure, and the transportation network connecting it to the rest of Palestine and the Arab world. More investments and jobs were also created for Jaffa’s residents through the increasing number of hotels, transportation companies, and the growing number of tourism-related services.

Jaffa was also the cultural capital of Palestine, being home to tens of the most important newspapers and publication houses in the country, including the dailies Filastin and al-Difa’. The most important and ornate cinemas were in Jaffa, as were tens of athletics clubs and cultural societies. The headquarters of some of these societies, like the Orthodox Club and the Islamic Club, have themselves become historic sites still testifying to the city’s cultural history. During the Second World War, the British Mandate authorities moved the headquarters of the Near East Radio broadcast studios to Jaffa, the studios becoming a cultural hub in the city from 1941 to 1948. With the growing cultural importance of Jaffa came increasing cultural exchange and interconnection with the main cultural centers in the region such as Cairo and Beirut, which further established the city as a cultural minaret in the region — lovingly dubbed the Bride of the Sea.

The story of Jaffa’s ongoing Nakba is the story of the transformation of this thriving modern urban center into a marginalized neighborhood suffering from poverty, discrimination, gentrification, crime and demolition since the initial wave of mass expulsion in 1948 to the present day.

British soldiers stop and search a Palestinian man in Jaffa, 1936. (Palestine Remembered)

The early years of Jaffa’s Nakba

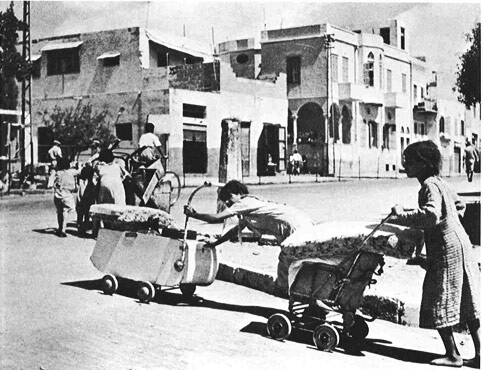

Zionist forces initiated a cruel siege on the city of Jaffa in March 1948. The youth of the city formed popular resistance committees to confront the assault. On 14 May 1948, the Bride of the Sea fell to the Zionist military forces; that same evening the leaders of the Zionist movement in Palestine declared the establishment of the state of Israel. Approximately 4,000 of the 120,000 Palestinians managed to remain in their city after it was militarily occupied. They were all rounded up and ghettoized in al-Ajami neighborhood which was sealed off from the rest of the city and administered as essentially a military prison for two subsequent years; the military regime under which Israel governed them lasted until 1966. During this period, al-Ajami was completely surrounded by barbed wire fencing that was patrolled by Israeli soldiers and guard dogs. It was not long before the new Jewish residents of Jaffa, and based on their experience under Nazism in Europe, began to refer to the Palestinian neighborhood as the “ghetto.”

In addition to being ghettoized, the Palestinians who remained in Jaffa had lost everything overnight: their city, their friends, their families, their property and their entire physical and social environment. Most had lost their homes as the Israeli military forced them into al-Ajami. Legislator, judge and executioner in the Ajami ghetto was the military commander; without his permission one could not enter or leave the ghetto, and rights to things like education and work were among those rights that Palestinians were denied. Arab states were classified as enemy states, and so making contact with the expelled family and friends, the refugees, was strictly prohibited. This was the nightmare lived by the Palestinians of Jaffa after the 1948 Nakba.

In the early 1950s, Jaffa was administratively engulfed by the Tel Aviv municipality that became known as Tel Aviv-Yafo; the Palestinians of Jaffa went from being a majority in their city and homeland to the two-percent “enemies of the state,” a minority of Israel’s main metropolis. The municipality immediately began drawing up plans for what they called the “Judaization” of the city, renaming the Arabic streets of the city after Zionist leaders, demolishing much of the old Arab architecture, and completely destroying the buildings in the surrounding neighborhoods and villages that were depopulated during the 1948 Nakba. The new curriculum introduced in Palestinian schools denied that the place had any Arab-Palestinian history at all, a facet of the Israeli education system that continues until today.

The largest armed robbery of the 20th century

After expelling most of Jaffa’s residents, militarily occupying the city and ghettoizing the remaining original inhabitants, Israeli authorities passed the Absentee Property Law (1950) through which it seized the property of all Palestinians who were not in possession of their immovable properties after the Nakba. Through the implementation of this unjust law, the state of Israel sent its operatives to all corners of the land, surveying the properties left behind by the expelled refugees, the internally displaced Palestinians banned from returning to their lands, and those relocated to the ghettos of Palestine’s cities. Title to these lands, buildings, homes, factories, farms and religious sites were then transferred to the state’s “Custodian of Absentee Property.” This is how the Palestinians of Jaffa, the refugees and the ghettoized, had their properties “legally” stolen by the State of Israel.

In the interviews conducted for our research, we heard dozens of stories from Nakba survivors telling us about how their homes, often just meters away from the ghetto, were seized, and how they could do nothing about it. Many told us stories of how their homes were given to, or simply taken by, new Jewish immigrants, and how they would try to convince the new residents of their homes to give them back some of their furniture, or clothes, or documents, or photographs. In some of these cases, the house’s new resident would give back some of the items, in most of the cases the response was to consider the original Palestinian owner an intruder, and to call the police or report him to the military commander. Former residents of the al-Manshiyya neighborhood, one of the city’s wealthier areas before the Nakba, described the sorrow they felt as they walked past their old houses, and the pain of seeing what remained of the neighborhood demolished to be replaced by a public recreation area.

Some of the most difficult stories are those of the Palestinian farmers and peasants from the villages of the Jaffa district. They describe how they were forced off of their land, how they managed to stay in Palestine, how the Israeli government handed their land over to Jewish settlers, and how these settlers then hired the same Palestinian farmers to work on their own land as day laborers exploited for the personal profit of the Jewish settler off the produce of the land that Palestinians had cultivated for generations. In fact, after their properties and enterprises were seized or shut down, the vast majority of the Jaffa Palestinians who remained became cheap labor for Jewish employers. Their employment was contingent on their “loyalty” to the new state. And so it was that the people who ran the economic hub of Palestine before 1948, became its orphans feigning loyalty to the ones who orphaned them in order to feed their own children.

Palestinians from Jaffa attempt to take with them whatever they can as Zionist militias force them to leave the city, May 1948. (Palestine Remembered)

The daily violations of co-habitation

After the creation of the State of Israel on the ruins of Arab-Palestinian society, the fledgling state began absorbing thousands of new Jewish immigrants from around the world, masses of immigrants whom the state was not fully able to absorb. The state resolved this lack of capacity by distributing the homes of refugee and internally displaced Palestinians to the new immigrants. After all the Palestinian homes in Jaffa had been occupied, Israeli housing authorities began dividing the homes in the Ajami ghetto into apartments so as to provide housing for Jewish families. As such, an Arab family in Ajami, who had been displaced from their original home, and whose family and friends had been expelled, and who lived in a house with four rooms, for example, would have their new home divided into four apartments to absorb three Jewish immigrant families, and the four families would share the kitchen and bathroom.

This process was one of the most difficult for the Palestinian families; they were forced into “co-habitation” with the people who had expelled them and, considering that many of the Jewish families included members who were serving in the army, people who were directly carrying out the ongoing violence suffered by the remaining Palestinian community.

The horrors of war, the loss of their country, the deep rupture in the social environment, the trauma of oppression, occupation, segregation and discrimination, the demolition or theft of their original homes before their own eyes, being forced to share their homes in the ghetto with the people who expelled them from their original homes, all combined to create an overall feeling of despair and impotence among the remaining community of Palestinians in Jaffa. This collective depression eventually led many of Jaffa’s ghettoized Palestinian residents down the path of dependency on drugs and alcohol as a way of escaping the burden of powerlessness in the face of colonial oppression. It was this form of colonial oppression that transformed the thriving Bride of the Sea to a poverty and crime-ridden neighborhood of Tel Aviv.

1951-1979: survival and self-improvement

The first generation of Nakba survivors faced immense hardship, and as such the main goal of that generation was survival in a milieu replete with fear of the Israeli authorities. The hope for a better life, for a return to how things once were, for freedom, became a motivating factor in their lives. This was especially true in the late 1950s and 1960s, when the Arab world went through the awakening epitomized by Nasserism. The ideas of Arab unity, Palestinian liberation, cultural revival and the hope entailed by these ideas found fertile ground in the Palestinian society within the “green line” (the 1949 armistice line between the State of Israel and the West Bank and Gaza Strip). This was the environment in which the second generation was raised.

The generation of the 1950s and 1960s grew up in an environment very different from that of their parents. This generation sought self-improvement, to work hard to provide for their families and educate their children by working the manual labor jobs that Jewish immigrants avoided. It was members of this youthful generation who filled the ranks of the Communist Party and the Nasserist Land Movement, among other political currents that aimed to challenge the prevailing oppression, poverty and landlessness of the Palestinian community to varying degrees.

In preparation for its occupation of the remainder of Palestine, and as internal opposition grew and information began to leak out that the “only democracy in the Middle East” actually had two sets of laws for two sets of citizens, the Israeli government formally abandoned the regime of military rule in 1966. While systematic discrimination against Palestinian citizens continued unabated, the 1970s witnessed the emergence of a relatively powerful political and social movement of Palestinian citizens of Israel. In Jaffa, this movement culminated with the formation of the Association for the Care of Arab Affairs in 1979. The Association was formed by activists and intellectuals who aimed to protect what remained of the city’s Arab-Palestinian identity and heritage, to fight the systematic discrimination faced by the Palestinians of Jaffa, and to spearhead campaigns on important issues facing the Palestinian community, foremost among them housing and education.

It was in this same decade that “Judaization” of areas within the green line became publicly known as official Israeli state policy. While the main theater of Judaization during the 1970s was the Galilee in the north of historic Palestine, the Palestinians of Jaffa continued to feel increasing pressure to leave their homes in the city through various discriminatory policies and practices, such as those banning Palestinians from renovating their homes since these properties were largely registered as absentee property with title held by the state. The municipal authorities had ignored the neighborhood, allowing many houses to collapse, and in some cases ordered the demolition of Palestinian homes. As a result of these deteriorating conditions, most of the Jewish residents of Ajami had moved to the city’s suburbs, and were beginning to move to the West Bank in the newly built illegal settlements where the cost of living was, and continues to be, heavily subsidized by the state.

1979-2000: the return of the spirit

The proportion of Palestinians in Jaffa had grown by the onset of the 1980s, both as a result of natural growth, and because a growing number of Palestinians displaced from the Galilee and the triangle ended up in Jaffa. Literacy and education levels among the adult Palestinian population in the city had also risen as the generation of the ’60s and ’70s grew and became active members of the society. This second generation benefited from the sacrifices of their predecessors, many of them having opened their own small enterprises like restaurants, contracting firms and car repair shops. A small number had also been able to complete post-secondary education in professional fields such as law, medicine, accounting, engineering and others. As such, the economic, social and demographic balance of the city had begun to restore itself.

Young Palestinian workers in one of Jaffa’s many orange groves, 1898-1914. (Matson Collection)

The improvement in the standard of living of Jaffa’s Palestinians that began in the 1980s involved the increase in the number of Arab owned and operated enterprises, the renovation of Palestinian mosques, churches and public buildings, as well as annual increases in the number of post-secondary graduates most of whom reinvested their acquired skills and knowledge in the betterment of their community. While the state and municipal authorities continued their Judaization efforts, the Palestinian community had become an active and effective player in the life of their city. Working against this economic development within the community has been the fact that the Israeli government has not invested or supported Palestinian-owned enterprise while simultaneously subsidizing and investing heavily in Jewish-owned enterprises in Tel Aviv. This economic discrimination has played an important role in making Palestinian Jaffa economically dependent on Jewish Tel Aviv.

The ’90s witnessed a powerful political and cultural revival among Palestinian citizens of Israel as the third generation since the Nakba began to discover and assert their Palestinian identity as the indigenous people of the land. The fear that had been a powerful force facing their grandparents did not affect them in the same way, and as a largely educated generation, the disparity between the ideals of “Israeli democracy” that they had learned in school and the discrimination they faced in their daily lives drew increasing members of this generation into the political arena. The growing national awareness of Jaffa’s Palestinians materialized during the outbreak of the second Palestinian intifada when the Palestinian youth of Jaffa protested the brutal Israeli military violence against the Palestinians of the West Bank and Gaza by organizing dozens of forums, protests, pickets and fundraising campaigns to stress the unity of the Palestinian people across borders.

Jaffa’s ongoing Nakba today

Despite the growth of Palestinian political and social movements, the more than 20,000 Palestinians living in Jaffa today continue to experience an ongoing Nakba. We do not use this description lightly, or to enlist tears of sympathy or nostalgia for what once was; it is an important way of understanding the present, entrenching the demand for redress for the crimes committed by Israel over the past 60 years, and to stress the urgency of the struggle to bring about change for the future. While systematic discrimination and Israeli policies and practices aimed at displacing Palestinians and Judaizing their space permeate all aspects of Palestinian life in Israel, we will focus on the fields of housing and cultural identity.

The most pressing issue facing Palestinians in Jaffa today is the issue of housing and eviction. Every Palestinian in Jaffa is either directly facing eviction by the municipal authorities, or has a neighbor or relative who faces such eviction, an estimated total of more than 500 families are in this situation. The two main excuses for eviction are lack of licensing — especially since licenses are almost impossible for Palestinians to obtain — or that the family is considered illegal squatters in their own home which is registered as state property.

Title to the vast majority of properties in Jaffa were transferred to the state through the implementation of the Absentee Property Law (1950), and the state transferred this title to Amidar, a state-run company managing state properties in urban areas. After focusing its Judaization efforts on the Galilee and the Negev, the state has now set its sights on Palestinians living in Palestinian cities, officially referred to as “mixed cities,” ordering their removal from homes in which they have lived for 60 years, and in some cases longer.

Mass eviction of Palestinians from their homes in these cities is a dual process. The first, and primary, aspect is Judaization aimed at changing the demographic character of these cities so as not to include significant numbers of indigenous Palestinians, and to erase the Palestinianness of the landscape. The second aspect is gentrification; in most cases these properties are slated for demolition to be replaced with expensive condominiums and housing units for the rich. As such, both the political merchants pandering to the ideologically-driven Zionist public, and the real estate merchants hoping to build and make millions off of their “development” projects stand to benefit. We should also note that the Ajami ghetto, while by far the poorest neighborhood in the Tel Aviv-Yafo municipality, is also a coastal neighborhood with some of the highest property value in the city.

The issue of Palestinian housing in Jaffa is more than the sum of its parts; it goes beyond the hundreds of eviction and demolition orders. One cannot but connect the dots between Amidar and the Israeli Lands Administration putting up tens of Palestinian homes for auction, the rapidly increasing property value, the construction of the Peres “Peace” Center on confiscated Jaffa refugee property, and the establishment of a center for Jewish fundamentalists in the heart of the Ajami neighborhood. The picture we see when the dots are connected is worrying, the original inhabitants of Jaffa are uprooted, and their place invaded by those who have money and power: the elites of the Jewish-Israeli establishment. We see the state handing out properties to Jewish settlers almost for free in other Palestinian cities like al-Lydd and Ramleh as well as in the Naqab (Negev) and now Jaffa, while we, the indigenous people of Palestine are dealt with as illegal squatters and intruders. We, the Palestinians who remained in the part of Palestine taken by the Zionist movement in 1948 and who were forced to accept the citizenship of the state that usurped our country, now form 20 percent of the citizens of the State of Israel, but only control 3.5 percent of the land after most of our land and property were confiscated by this state. Since its establishment, Israel has created hundreds of new communities for Jewish settlement, but not one new community for Palestinians.

Jaffa’s clocktower, approximately 1914. (Matson Collection)

Reshaping identity, language and history

One of the most prominent landmarks in the city of Jaffa is the clocktower built by the Ottomans at the entrance to the old city, long before Israel came into being. Today, Jaffa’s visitors and residents who care to take a look at the structure see a Hebrew-language plaque that states “In Memory of the Heroes who Fell in the Battle to Liberate Yafo.” From there, if we turn right to walk up to the old city we catch a breathtaking view of the Mediterranean Sea until we reach the informational signs posted by the Tel Aviv municipal authorities. Here we can read the history of the city covering thousands of years until the present day. One may be surprised to see that these signs are written in four languages, none of which are Arabic. More astonishing is that in none of these appears any mention of Arabs or Palestinians who only pop up in one line: “in the year 1936, Arab barbarians attacked the Jewish neighborhood.” More examples of the systematic erasure of the Arab-Palestinian history of the space abound, from the replacing the names of streets, neighborhoods and other landmarks in the city with Hebrew names, most often names of Zionist political and military figures.

An important aspect of the reinvention of Jaffa as an Israeli city, in addition to burying its Arab-Palestinian identity, is Israel burying the evidence of its crime. If we are to accept that there were no Palestinians here, then there were no Palestinians for Israel to kick out. The erasure of Palestinian memory is also strongly reflected in the Israeli education system in Arab schools where the curriculum is geared toward rearing Palestinian youth, ignorant of their identity and history, and loyal to their colonial oppressor.

After the 1948 Nakba, Arab schools came under the control of the Israeli Ministry of Education, through which the Israeli intelligence services play a direct role in the selection of principals, teachers and curricular materials. In social science and humanities classes, Palestinian students in Israel learn about the history of Jewish communities in Europe, the heroic establishment of the modern Jewish state with no mention of the catastrophe that befell the indigenous Palestinian society of which they are a part. Schools are also a site of intimidation against any politicization, especially on important commemoration dates of the Palestinian struggle such as Land Day or Nakba commemoration. For the most part, Arab public schools are largely neglected in the allocation of funding and resources, and the quality of education is very low relative to the schools of the Jewish community. This drove many Palestinian parents in Jaffa to send their children to Jewish schools, a phenomenon that amplified the identity crises facing many of the city’s Palestinian youth, as well as their difficulty with the Arabic language.

Jaffa: the struggle continues

A view of Jaffa from the north beach looking south, 1900-1920. (Matson Collection)

Beginning systematically in the 1970s, the Palestinian rights movement consistently challenged Israeli policies and practices with such mobilizations as the 30 March 1976 general strike commemorated as Land Day, and the hundreds of actions taken in support of the first and second Palestinian intifadas. The movement pushed the Palestinian struggle out of its superficial national and religious confines to an internationalist struggle in which Palestinians and Jews struggled side-by-side for justice. In Jaffa, this struggle has managed to bring about some tangible victories, among them stopping the municipality from transforming the beach into a waste-dumping ground, pressuring the Israeli authorities to build housing units for Palestinians in the city, and establishing independent Arab educational institutions such as a nursery and the Arab Democratic School which opened its doors to students in 2003. This struggle has been the main factor enabling Palestinians to remain steadfast in their historic city.

Today, the struggle continues under the banner of the Jaffa Popular Committee for the Defense of Land and Housing Rights (also known as the Popular Committee against House Demolition in Jaffa) which was established in March 2007 as a direct response to the hundreds of eviction orders issued to the Palestinian residents of the Ajami and Jabaliya neighborhoods of Jaffa. The importance of the Committee’s work soon became clear to its members when their preliminary research revealed that 497 Palestinian homes in Jaffa were under threat of eviction and/or demolition by the Israeli Lands Administration, which had also put up many of these properties — all of them “absentee” properties — for auction. The Popular Committee is made up of residents, social and political activists, movements and organizations and political parties operating in Jaffa. The Committee represents the collective struggle of Jaffa’s Arab-Palestinian residents, and is open to membership to anyone who agrees to its demands and political basis of unity.

A central aspect of the Committee’s work is pressuring the various arms of the Israeli authorities (the Israeli Lands Administration, Amidar, Tel Aviv-Yafo Municipality) to freeze all legal actions taken for the purpose of eviction, demanding that these authorities enter a dialogue with the Committee instead, in order to reach an agreed-upon solution. The Committee also demands an end to any and all sale and auction of “publicly owned” (i.e. absentee/refugee) land, and entering a dialogue with the committee to implement a system that guarantees the long-term Palestinian presence in the city, and that enables youth and young couples to find affordable housing in the city, particularly in the Jabaliya and Ajami neighborhoods. The motivating spirit of the campaign launched by the Popular Committee is the need to wrest recognition of Jaffa’s Arab-Palestinians as a group with a historic rights to the land and properties of the city, and that as such, alternative solutions to Jaffa’s housing problem must be reached in consultation and with the consent of indigenous community.

The Popular Committee also works on information gathering and research mainly from the directly affected residents of Jaffa facing eviction and home demolition; direct action to prevent eviction and home demolition which has involved mobilization of activists to be physically present in homes slated for demolition; organizing popular activities such as pickets, protests, information forums and others; as well as a media campaign to raise awareness about the plight of Jaffa’s Palestinian community in local and international media. We are constantly looking for ways to fundraise both for our legal costs and for activities to enable youth, women, and young couples to find affordable housing. Increasingly the committee has taken on organizing extracurricular activities for youth, and workshops to support women and youth to run their own businesses with the understanding that the economic viability of the community is directly linked with our ability to remain steadfast.

Reversing the ongoing Nakba

Today the estimated number of Palestinian refugees from Jaffa hovers around 700,000, which is one-tenth of the Palestinian refugee population. While most of these refugees are in Gaza, the West Bank and Jordan, many are further away with foreign passports that can enable them to visit what remains of their city. Perhaps one of the most important steps in reversing the Nakba, which involved shredding up the Palestinian body and dispersing us to various far corners of the earth, is to intensify efforts to reconnect this body. If it is not physically possible because of Israeli travel restrictions on Palestinians, the Internet and other communication technology can play an effective role in this process.

At least as important is the international solidarity needed to stop the Israeli policies and practices that constitute the ongoing Nakba. In Jaffa, the ongoing Nakba has brought about ongoing resistance. This resistance may not be able to turn back the clock, and we may not be able to live as if the past 60 years never happened, but at least we can work to prevent further suffering and destruction of our city and our society, and we can work to rebuild the eminence that was the Bride of the Sea.

Sami Abu Shehadeh and Fadi Shbaytah are residents of Jaffa, and members of the Jaffa Popular Committee for the Defense of Land and Housing Rights. This article was translated from Arabic by Hazem Jamjoum, and was originally published in the upcoming (Autumn 2008/Winter 2009) issue of al-Majdal, the quarterly magazine of the Badil Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights (http://www.badil.org/).