The Electronic Intifada 15 June 2007

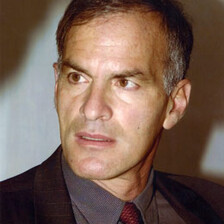

On Friday, 8 June, DePaul University President Dennis Holtschneider announced that he had decided to uphold the university’s tenure and promotion board’s ruling denying outspoken political science professor Norman Finkelstein tenure. In a press release, the president is quoted as saying that academic freedom “is alive and well at DePaul University.” Not surprisingly, the announcement of Finkelstein’s tenure denial has spawned a national discussion. Academics everywhere have been forced to ponder the implications for the future of academic freedom in the United States, especially those who dare to criticise US and Israeli policy in the Middle East.

Finkelstein, the son of Holocaust survivors, has been relentless in exposing what he calls “The Holocaust Industry”: the institutions and organizations that have used the holocaust (the actual historical event) to justify Israel’s criminal assault upon the Palestinian population and international law. Among these organisations, he includes the World Jewish Congress, the Anti-Defamation League, the American Jewish Committee, and a host of other fellow travelers. There is no doubt that Finkelstein’s work has stoked controversy. But that shouldn’t detract from what makes his tenure treatment so worrying: Finkelstein is undoubtedly a path-breaking and serious scholar.

Raul Hilberg, the leading scholar on the Nazi holocaust, has called Finkelstein’s The Holocaust Industry “a breakthrough” and states that Finkelstein “was on the right track” in his documentation of how the World Jewish Congress, with the aid of the Clinton administration, extorted billions of dollars from Swiss banks in the name of Holocaust survivors, only to pocket the money for Jewish organisations. And, although The Holocaust Industry is Finkelstein’s most frequently cited book in defamatory attempts to cast him as a “Holocaust denier” and a “denier of justice to Holocaust survivors”, Image and Reality in the Israel-Palestine Conflict — a thorough criticism of the central political and philosophical tenets informing Zionism — is his most scholarly and substantial work. But Finkelstein’s detractors avoid discussion of Image and Reality for exactly that reason: it is considered a first-rate piece of scholarship.

Finkelstein argues that most US commentators obscure or avoid the clear historical and diplomatic record in examining the Israel-Palestine conflict by ignoring or downplaying international law, fooling the US public into believing that Israel’s occupation is just, necessary, and lawful. One such example is the failure of the 2000 Camp David talks — a failure that has been attributed, at least in elite circles within the United States, to Yasser Arafat’s intransigence. In actuality, what Bill Clinton and Ehud Barak offered Arafat was something no Palestinian leader could accept: a Bantustan state reminiscent of the African national territories.

Finkelstein’s latest exposure of US and Israeli apologetics for state violence was of famed Harvard Law Professor Alan Dershowitz, who was at the centre of Finkelstein’s analysis in Beyond Chutzpah: The Misuse of Anti-Semitism and the Abuse of History. In August 2003, Dershowitz published The Case for Israel, which Finkelstein uses as a foil in Beyond Chutzpah, demonstrating that Dershowitz misrepresents key diplomatic, legal and historical aspects of the conflict. Dershowitz attempted to block publication of Beyond Chutzpah by inundating the University of California Press with threatening letters from the major New York law firm of Cravath, Swaine, and Moore throughout the spring and summer of 2005, stating he would sue the press if it did not ensure that every claim Finkelstein made about Dershowitz was factually correct. Beyond Chutzpah was vetted by six experts of the Israel-Palestine conflict and several libel attorneys. When he could not prevail upon the press or the University of California’s Board of Reagents, Dershowitz asked Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger to intervene. Schwarzenegger refused to do so on grounds of academic freedom. Finkelstein wasn’t so lucky at DePaul.

But, by all accounts, Finkelstein far exceeds DePaul’s teaching and publication requirements; indeed, he has the teaching and publication record for full professorship. His tenured colleagues in the political science department voted 9-3 in favour of his tenure and promotion to associate professor. (And the three professors who voted against Finkelstein’s tenure are not experts on the Israel-Palestine conflict or the holocaust.) The college’s personnel committee unanimously upheld the department’s recommendation in a 5-0 vote.

In a memo dated March 22, Dean of Liberal Arts and Sciences Charles Suchar withheld support of Finkelstein’s tenure application and agreed with the authors of the minority report, arguing that Finkelstein’s tendency to engage in demeaning and reputation-damaging attacks compromised the quality of his scholarship. The dean invoked “Vincentian Personalism” as a tenure criterion, and reported to the university’s board that Finkelstein has an “apparent penchant of reducing an argument and oppositional views to the inevitable personal and reputation damaging attack, demeaning those with whom he disagrees.” Surprisingly, these concerns had never been raised about Finkelstein’s work previously by DePaul’s administration.

To thank for these new concerns we have Alan Dershowitz, who distributed an “information packet” to the faculty and waged a one-man war against Finkelstein. Throughout the months of April and May, Dershowitz availed himself of the pages of the New Republic, FrontPage magazine and even the Wall Street Journal to attack a world-renowned scholar and one of DePaul University’s most accomplished teachers. Dershowitz has maintained that the Finkelstein case is not about academic freedom but about academic standards. DePaul administrators ended up rationalising the tenure denial along similar lines. That Finkelstein’s opponents have succeeded should give pause to anyone concerned about academic freedom in the United States.

Matthew Abraham is an assistant professor of English at DePaul University and is guest editor of a special issue of Cultural Critique on the life and legacy of Edward Said entitled “Edward Said and After: Toward a New Humanism” and his work has appeared in The Journal of Culture and Religious Theory and Logos: A Journal of Culture and Ideas.

This commentary was originally published by The Guardian’s Comment is Free and is republished with the author’s permission.

Related Links