The Electronic Intifada 11 July 2006

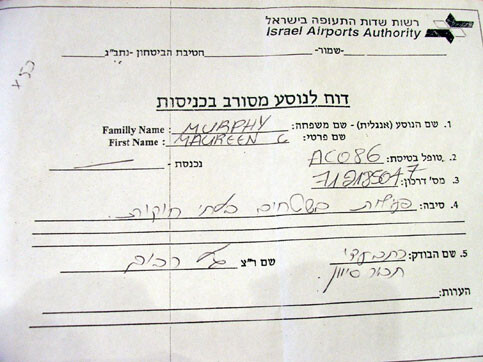

Two passports, no entry: Both of my passports marked by the dreaded red stamp (Maureen Clare Murphy)

In another Israeli move designed to further isolate Palestinians from the rest of the world community, it is being reported that the Israeli army will be declaring the West Bank closed to foreign nationals. The Gaza Strip has already been made virtually inaccessible to foreign nationals; those who wish to enter must apply to the Israeli authorities, weeks in advance, to receive elusive permits. The effect is that the plight of the Palestinian civilian population living under Israeli occupation becomes all the more invisible to the international community.

The recent trend of deportation of foreign nationals (including foreign passport-holding Palestinians) working in Palestinian civil society, studying at Palestinian universities, and those living with Palestinian family gives further cause for concern that West Bank Palestinians will no longer be allowed visitors to their open-air prison. Of course, this policy of isolation is being justified under the guise of “security.” The rightist Israeli daily Maariv reports, “According to the plan, the IDF will declare the Judea and Samaria [the West Bank] closed to foreign nationals. Denying entry to … activists has been defined as prevention of political subversion and involvement of members of the movement in acts of terrorism, and limitation of friction with Jewish settlers.”

However, Israel has long been denying entry to scores of internationals whether they are activists or not — a policy that has been intensified in recent months. During April, after having lived in Ramallah for a year and a half and staying on a tourist visa that I would renew every three months, I was denied entry to the West Bank from Jordan via the Israeli-controlled Allenby Bridge land crossing, and given no documentation to indicate why I was being turned away. On the Jordanian side of the bridge, security officials there told me that scores of international passport-holders — Palestinian-Americans in particular — were being denied entry into the West Bank.

I eventually managed to get back in with a one-month visa after having been issued a new passport by the US Embassy in Jordan, but was deported from the airport in Tel Aviv a month and a half later. There, I was informed that I was declared “persona non grata” as it was believed that I was trying to “illegally settle in Israel,” despite that I informed them that I was living in the West Bank city of Ramallah. In any other country, staying too long on a tourist visa would be an understandable reason for deportation. However, the Palestinians have no control over their borders, and the former system that allowed foreign passport-holders working and living in the West Bank and Gaza to obtain a work permit or other special visa so they would be able to stay a prolonged time has been terminated by Israel. Denied a hearing and any further legal recourse, I was merely given a very unofficial-looking piece of paper from the Israeli authorities as they shoved me on a plane back to Toronto. However, the document was in Hebrew, a language neither I — nor the Canadian immigration officer I had to explain myself to once I landed — could read.

“I was deported from Israel and all I received was this lousy piece of paper”

The only documentation I received upon my expensive deportation from Israel. Unlike what I was told verbally, it says here that the reason I was denied entry was because of “illegal activity in the ‘territories’ ” (Maureen Clare Murphy)

Control of all movement

The threat of Israeli deportation is the great existential fear that hangs over all expatriates’ heads in the occupied Palestinian territories. Conversations with other expats would always lead to the recounting of recent “visa run” experiences, when we would dash to nearby Jordan or another country for a visit and then return to obtain a new three-month B-2 tourist visa. Those working with UN agencies or major international organizations often held work permits; but for those of us recently working in Palestinian civil society, there was no known mechanism for acquiring such a permit without the backing of a major organization. And for those few brave souls who did try to forge new ground and apply for a permit as individuals, not even hiring the best of lawyers would guarantee that this would occur.

In the post-Oslo Accords era, it used to be that internationals working in Palestinian civil society would be able to apply for a work permit from the Israeli civil administration in the West Bank via the Palestinian Authority as a matter of course. But this has not been the case for some time. A European friend working for a Palestinian civil society organization recently rang the Beit El/DCO checkpoint, which houses an Israeli West Bank civil administration office. She was told that to cross the checkpoint, she would need a work permit from Israel and that she should apply for one from the Israeli Ministry of Social Affairs. However, the Israeli official added, “I will tell you now that it will be impossible because they will refuse you once they know you are working for an organization that is working in the territories.”

Internationals working with Palestinian organizations are left with little options for entering the Israeli-controlled borders in a “legitimate” manner. Some choose to lie about what they do when asked their purpose of visit, knowing that mere mention of the word “Palestinian” would cause them to be red-flagged in the Israeli system. Optimists like myself think that when in doubt, err on the side of truth. Also, not skilled in the art of lying, I thought it a moral point to not be made to feel as though working for a respected Palestinian human rights organization was anything less than legitimate. But we all knew that our fates would be arbitrarily determined, for there is no established and transparent process for ensuring entry.

Amongst expatriates living in Ramallah, there were stories of spouses of West Bank ID-carrying Palestinians who have been continuously getting the three-month B-2 tourist visa for as many as twenty years, by coming and going to Jordan several times a year. These individuals had acquired the status of legends amongst the expat community, though the precarious situation of international passport-holders (including Palestinians living in the diaspora) who marry and have families with Palestinians holding West Bank or Gaza ID cards is all too real. Thousands of Palestinian families perpetually live in fear of a family member being deported — a worry shared by my corner shopkeeper with an American passport-holding wife who goes to Jordan and back every three months, and a friend whose American sister-in-law simply overstayed her visa for five years, knowing this would mean she could never return once she left.

Recently, this fear has been confirmed; countless families in which one or more members hold a foreign passport have found themselves fractured by the denial of entry of one of their members. Many of these are middle class families headed by diaspora Palestinians who returned to help develop their country during the post-Oslo years. As a Palestinian official who holds a European passport pointed out to me, “this is particularly symbolic since, by choosing to return to Palestine, these people represented the optimism of the Oslo years and personified the state-building project.” If this trend continues, a whole segment of the Palestinian middle class may be dispersed, taking with them their business investments and entrepreneurship, leaving the Palestinian economy that much more unstable.

On top of this, there are the countless numbers of Palestinians who at one point left (or were forced out from) their country and are not allowed to re-enter with the passport of their adopted country. This was the case with a colleague’s European passport-holding brother, who was denied entry to the West Bank via Allenby Bridge around the same time as myself. And while he was taking me to the American embassy in Amman where I would pick up my new US passport, a taxi driver from the West Bank city of Nablus recounted how he left to work in Jordan some years ago, leaving behind his wife so she would not be separated from her family. Having lived outside the West Bank for too long, the Israeli authorities did not let him return, and so he and his wife continue to live apart.

Holding his West Bank ID up for inspection, a Palestinian man attempts to pass Al-Ram checkpoint to Jerusalem shortly before the Friday noon-time call to prayer during the holy month of Ramadan (Maureen Clare Murphy)

Palestinians are left unable to reach places of worship, education and health services, and even family members - breaking social, economic, and cultural structures. Israel imposes such policies for “security” reasons, but the terms that more accurately reflect reality are collective punishment and oppression. These movement restrictions are becoming increasingly formalized by million dollar checkpoints-cum-terminals, suggesting that the intention is actually to strengthen Israel’s grip on the occupied territories and establish “facts on the ground” to preempt a negotiated resolution to the conflict.

When Israel began building its new “Atarot Crossing” terminal between Ramallah and Jerusalem where the former Qalandiya checkpoint lay, rumors began to fly that the thousands of Palestinian Jerusalemites holding Israeli permanent residency cards would have to obtain permits to cross to Ramallah and the northern West Bank. Since the new terminal has been in use, this hasn’t been the case (though since the beginning of this month, they not able to pass through a similar terminal at the entrance to Bethlehem), but many believe that there is no telling when such a policy could be put into place. The permanency of the technologically sophisticated structure gives weight to such speculation. Why would so much money be invested in a temporary security measure? The same question must asked of Israel’s barrier in the West Bank, the current route of which effectively annexes ten percent of the West Bank to Israel, and isolates Palestinian communities from one another.

Replacing the eminently more temporary-looking former Qalandiya checkpoint, the new “Atarot” crossing terminal is complete with LCD monitors misspelling greetings in English (Maureen Clare Murphy)

Dangerous silence

Earlier this year, then-Acting Prime Minister Ehud Olmert told the Israeli daily Ha’aretz of the new scope of impunity that Israel enjoys following last year’s unilateral disengagement from Gaza. Regarding the state’s illegal assassination operations in Gaza, he bragged, “there is not a single word of criticism anywhere in the world. And do you know why? Because the disengagement gave us degrees of freedom in carrying out everyday security activities, which we never had before … The day before yesterday we carried out a targeted interception [sic] in Gaza. The day before that we did another targeted interception [sic]. Not a critical remark, not a hint of critical remark, has come from anywhere in the world.’”

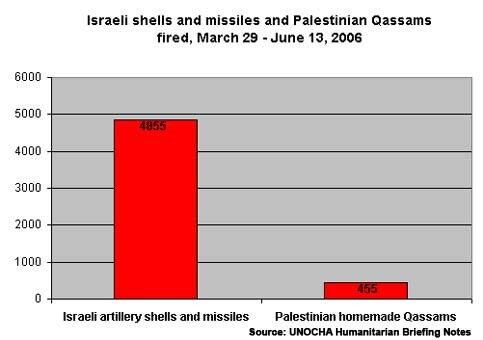

The international community’s silence has been deafening as Israel routinely drops missiles onto Gaza — one of the most densely populated areas of the world — in its illegal extrajudicial assassinations, and is currently embarking on its indefinite deployment there. Of course, the civilian casualty count has been predictably high. When asked to, Israel justifies such operations as necessary to deter the launching of crude, homemade Qassam rockets from the Gaza Strip into Israel. But such measures are not in compliance with the legal principle of proportionality, and the daily shelling of the Gaza Strip amounts to another form of collective punishment of the Palestinian civilian population. Meanwhile, Olmert has been meeting with world leaders to secure international support of his “convergence plan,” the latest Israeli euphemism for unilaterally determining final-status negotiations issues. But the foundation of these unilateral plans has already been laid. With much of the Wall and the new permanent checkpoints in place or under construction, the architecture for new, Israeli-determined borders is already there.

The numbers speak for themselves: Israel’s disproportionate response to Qassam rockets amounts to collective punishment

Though not accepting the scheme hook, line and sinker, the international community is greeting this latest unilateral plan as the “only one in town,” despite past affirmations that a bilateral negotiated resolution to the conflict is the only way to move forward. With the international community’s boycott of the democratically elected Palestinian government, half of them currently in Israeli detention, the Palestinians are as powerless to claim their rights as ever. Worsening the situation, now that it is becoming increasingly difficult for international observers to access the West Bank and Gaza Strip, Palestinian civil society institutions will be losing invaluable conduits of advocacy to the outside world. The international community will become all the more blind and deaf to human rights abuses and rights violations committed in the occupied Palestinian territories. While Olmert will continue to enjoy the warm company of fellow statesmen, Palestinian civilians will become increasingly isolated under Israeli occupation.

What will be the effect on Palestinian society if internationals working in Palestinian civil society are not allowed to conduct their work, and Palestinians who returned to develop their country are forced to leave? With Palestinian voices largely absent from mainstream corporate media coverage of the conflict, who will be there to communicate the everyday devastation of Israeli occupation and unilateralism to the rest of the world? With a toothless international community, including consulates in Jerusalem who privilege Israel’s policies over the rights and interests of their own citizens that they are meant to protect, the outlook is indeed grim.

When I sought advice from the US Embassy in Jordan after being turned away at Allenby bridge, I was told that while Israel has the right to control its borders, at a certain point the turning away of American citizens (while Israeli citizens are not kept from entering the US) becomes “a bilateral issue.” Despite this, after I was deported from the airport, the response from the US consulate in Jerusalem was that tighter restrictions on foreigners entering the West Bank was understandable given the growing tensions between Hamas and Fatah. Other Americans who have contacted the consulate have been told a similar story. However, one has a hard time believing that any sweeping policy denying international passport-holders entry is actually in the interest of safety, rather than to remove some of the most credible and able — as far as international news audiences are concerned — persons likely to witnesses and protest Israel’s designs on the West Bank.

Related Links

Arts, Music & Culture Editor of The Electronic Intifada, Maureen Clare Murphy had spent the last year and a half living in the West Bank city of Ramallah and working for the Palestinian human rights organization Al-Haq before being deported late May