The Electronic Intifada 24 October 2005

Protest of women and children against the Wall in Jayyus. (Photo: StopTheWall.org)

On 26 September 2005, the Palestinian Counseling Centre (the PCC) announced the results of a survey on the psychological implications of the construction of the wall on people from five villages in the Qalqilya district. In 2003, the PCC conducted a pilot study, which was followed by the survey from early 2004 to August 2005.

Given Israel’s control on movement, it is a major achievement that the PCC was able to carry out the research. The PCC fieldworkers and staff were faced with measures that presented tremendous challenges to the researchers. These included being prevented from entering Palestinian villages without Israeli permission, assault and humiliation at the gates to the wall, including body searches as well as document searches, and time limitations upon entering the villages due to the opening and closing of the gates at times scheduled by the Israeli army.

Fortunately, the commitment of the researchers made it possible for them to overcome these obstacles. For example, at times fieldworkers and the PCC staff slept in the villages in order to carry out the study and therefore not be dependant on the Israeli army for entrance.

The research makes it clear that there is a positive correlation between exposure to the wall and psychological symptoms on adults as well as children. It is disturbing to note that children showed symptoms of agitation, verbal violence, nightmares and concentration problems.1

The Rights of the Child

The 1990 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child brings together children’s civil, political, social, economic and cultural rights in a holistic way. All of the rights defined in this Convention are seen as necessary for the full and harmonious development of the child’s personality and as inherent to the dignity of the child. Every country in the world has ratified the Convention except for the United States and Somalia.

In article 6, it is stated that a child has the right to life. Governments should “ensure that children survive and develop healthily”.2 Article 19 states that governments should “ensure that children are properly cared for, and protect them from violence, abuse and neglect by their parents or anyone else who looks after them”. Further to this is article 27, which says that a child has a “right to a standard of living that is good enough to meet its physical and mental needs”. The government should help families who cannot afford to provide this. Finally, article 38 concerns the right to receive “special protection” in war zones.

In 1991, Israel ratified the Convention. It is therefore bound to respect and promote the rights of all children in Israel and in the occupied Palestinian territories, as contained within the Convention.

The study

The study of the PCC was implemented in five villages in the Qalqilya district that are most affected by the wall, namely Azzoun, Atneh, Falamia, Ras Tireh, Mgharat al-Dabaa and Wadi al-Rasha. A random sample of 945 males and females was collected, including 314 adults (aged 19 years and over), 313 adolescents (aged 13 to 18 years) and 318 children (aged 6 to 12 years). For each age group a questionnaire was used to collect general information and data on economic status, exposure to the wall (for example, distance, function, passing through), traumatic incidents faced in the past six months, psychological symptoms due to exposure to the wall and coping mechanisms.

Impact on adults

An important finding of the study is the high incidence of fear and sadness in adults, and especially in women. Of the women responding to the study, 19.4 per cent suffer from these symptoms on a permanent basis and 60 per cent experience these symptoms occasionally. More specifically, women in Wadi al-Rasha and Mgharat al-Dabaa, where the wall has a high impact on economic, social and geographical aspects of the lives of the villagers, the rates were high.

Men over 40 years old showed a lack of motivation to perform daily activities. The study showed that 6.36 per cent of the adult men and 5.4 per cent of the adult women suffered from symptoms of paranoia. This feeling can be the result of men losing their source of income and their capacities, such as loss of (part of) the land or fear of confiscation of their homes, which can harm their families.

Positive correlation between exposure to the Wall and symptoms existence in children and adolescences

Statistical analysis showed that there is a strong relationship between exposure to the wall and feelings of loneliness, difficulty in breathing and stomach pains. Adults resort to long sleeping hours and isolation from others as means of dealing with the symptoms.

Impact on children

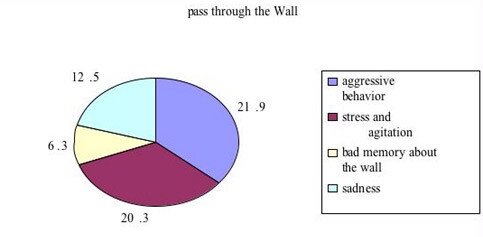

According to the parents, children between six and twelve years of age have become more aggressive: 59 per cent of the males and 41 per cent of the females showed aggressive symptoms occasionally while 9 per cent of the males and 6.7 per cent of the females showed these symptoms on a permanent basis. In addition, 40.8 per cent of the children in this age group showed symptoms of fear of the night (noctiphobia) on a permanent basis. According to the PCC, this means fear of the unfamiliar and the unknown and indicates fear of the future and feelings of insecurity.

Children symptoms

The study showed a proportional relationship between exposure to the wall and the occurrence of nightmares and aggressive behaviour in adolescents and children, causing them to act violently towards other children and to use impolite language. Children indicated that sharing emotions and bad experiences with parents was the main technique they used to deal with their feelings.

Mental health of refugee children in the Netherlands and England

Comparisons of the mental health of other highly vulnerable groups, including asylum seeker and refugee children in other countries helps to put the situation of the Palestinian children in perspective. In the Netherlands,3 asylum seekers and refugee children may live for many years in reception centres, where moving from one centre to the other is more the rule, rather than the exception. As a consequence, the continuity and stability of the lives of asylum seeker children is more frequently interrupted. For many years, it is not clear if they will receive a permit to stay. In general, they live in an environment that is hostile towards foreigners and they may have to confront discrimination and racism. Essentially, they live in an unstable and insecure environment.

Research on 154 children aged between 4 and 12 years undertaken in the Netherlands4 has shown that asylum seeker children suffer from poor mental health. 53.9 per cent suffer from mental problems, 4.5 per cent from serious mental problems. 30.5 per cent of refugee children have problems with sleeping, 27.3 per cent suffer from behavioral problems (such as aggressive behaviour) and 14.9 per cent wet the bed. This information is consistent with that of British researchers5 Fazel & Stein (2003), which showed that more than a quarter of refugee children suffer from ‘a significant psychological disorder’, three times more than English children. According to this research, refugee children are more hyperactive and have more problems with peers than English children.

Children seem to adapt easily, but their welfare depends to a large extent on the strength of their parents: “As long as the latter give the impression that they stand firm as parents and offer protection, children seem to make the best use of their resilience. If the parents have serious problems, the children will suffer directly and indirectly from this; directly because parental care falls short, indirectly because their parents’ suffering affects the children profoundly.” (Tuk, 2004)

The PCC’s study makes it clear that the wall has an impact on the mental health of adults and children. According to the PCC, the wall can be seen as a construction meant to confine and isolate people, which are the key characteristics of a prison. The gates may be compared with the doors of prison cells. The wall is monitored by devices and guarded by soldiers, and those who try to get out or cross the wall or enter through gates at “inappropriate” times risk arrest or getting killed.

In psychological terms, the wall is an ‘environmental stimulant’ (seeing the wall) followed by spontaneous ideas and concepts (for example, I live in a prison) and then by emotional, behavioural and psychological responses (tension, fast heartbeat and moving away from the gate).

Normal responses to an abnormal situation

The mental and behavioural problems of refugee children living in the Netherlands and England as well as of Palestinian children living in the Qalqilya district should be regarded as normal responses to an abnormal situation.

The wall affects adults and children. Adults have moved beyond the critical stages of growth and have formulated an independent personality. However, it should be noted that given the duration of the occupation, many adults have already faced occupation related hardships as a child. Children growing up in the vicinity of the wall are challenged to develop into stable, independent personalities while the key messages they receive every day through the presence of the wall can be a direct attack to their sense of self esteem and are therefore a major threat to their development. Just like the children of asylum seekers and refugees living in the Netherlands, they are living in an unstable and insecure environment. They need support from their parents and their community.

Ultimately, the best contribution to the development of Palestinian children would be for Israel to act on its responsibilities as a signatory of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. To bring an end to the occupation would be a crucial and straightforward contribution to the improvement of the quality of the life of Palestinian parents and children.

Adri Nieuwhof is a psychologist and human rights advocate and has worked for many years with asylum seekers and refugees in The Netherlands

Endnotes

[1] For more information on PCC www.pcc-jer.org.

[2] Convention on the Rights of the Child, adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989, entry into force 2 September 1990.

[3] Bram Tuk, Health, Safety and Development Conditions of Young Asylum Seekers in the Netherlands, December 2004; Pharos

[4] Sokal, D., Psychische problemen van asielzoekerskinderen in de leeftijd van 4 - 12 jaar. Utrecht, NSPH, 2001.

[5] Fazel, M & Stein, A., A Mental Health of Refugee Children study, British Medical Journal nr 237 (19 July 2003), p 134.

Related Links