The Electronic Intifada 1 February 2005

Palestinian children. (Cees Otto)

South African children. (UN Photo)

Despite some initial optimism following the outcome of the Palestinian presidential elections, there has been no obvious progress towards peace negotiations. This is of little surprise, since the conditions for holding negotiations simply do not exist and possibly have not even been thought through by either party. While opportunities for peace talks are fast disappearing as the region appears again to slide into outright confrontation, the writers, former anti-apartheid activists from the Netherlands, South Africa and Great Britain respectively, look back on this crucial period in South African history in the first of two articles in a series, to reflect upon and provide inspiration to the Palestinian struggle for liberation.

Release of Nelson Mandela

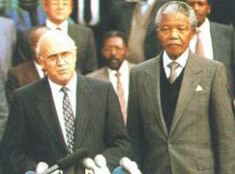

On 11 February 1990, the majority of South Africans celebrated the release of Nelson Mandela. There were a large number of television cameras from South Africa and around the world to broadcast the first images of the African National Congress (ANC) leader as he took his first steps towards freedom after nearly 28 years of incarceration. Finally, the world would get to know Nelson Mandela, who, until then, had been regarded by many white South Africans, Europeans, world leaders and government officials as a “terrorist”. During the elections that followed in April 1994, a peaceful transition of power took place and Nelson Mandela was elected as the country’s new president. However, while Mandela’s leadership clearly played a decisive factor, the transition to democracy involved far more.

From secret negotiations towards a constitutional dispensation

These bold, unilateral moves of then President F W de Klerk showed that his government was serious about change. These moves paved the way for full-scale negotiations on a new constitution, the bedrock of South Africa’s emerging democracy involving all parties, a process that took almost four years.

Paradigm shift

After more than 40 years of oppressing the black population, expropriating the country’s resources and brutally suppressing calls for democratic change, apartheid President De Klerk and other white Afrikaner leaders succumbed to pressure and came to the conclusion that fundamental change was needed in South Africa. Demographic pressure was one reason for this paradigm shift. The black South African population grew faster then the white South African population. It was clear that in the future it would be an almost impossible task for the white South African minority to control the 80% black South African majority of the population.

The deplorable state of the economy was a threat for the future, the almost complete international isolation of “white South Africa” and the rising tide of anti-apartheid protest both inside and outside South Africa’s borders all made it clear that it was not only morally but also financially and politically impossible to continue the oppression of black South Africans. Finally, the outreach policy of the ANC made it clear that change was possible.1

The current situation in Israel is reason enough for Prime Minister Sharon to reach the same conclusion as De Klerk did. His plan for withdrawal from Gaza is an implicit acknowledgement (albeit partial) that Israel, with its current policies, is heading down a dead end street.

In the aftermath of the recent (yet problematic) elections in Palestine, it is the task of President Abbas and the other Palestinian leaders, for their part, to develop an outreach policy to Israel’s leaders in different sectors of society. Israel, on the other hand, must demonstrate its commitment to a sincere engagement with Palestinian leadership.

The international community needs to reiterate their long-standing commitment to peace. Following in the footsteps of the ANC, Abbas would do well to persistently repeat this commitment to peace, together with his acceptance of the state of Israel as a starting point for negotiations.

However, a comprehensive strategy also needs to be developed towards reaching this end, including a clear and consistent communication of this strategy. As was also the case for South Africa, the views of the International Court of Justice and the United Nations Charter together provide Palestinian leaders with all the legitimacy they need to insist upon a negotiated transition towards full democratic dispensations.

End of violence as precondition to talks?

Despite many reported problems in the recent Palestinian elections,2 Mahmoud Abbas was chosen by the Palestinians, who were able to participate, to be their new leader. Sharon appeared to welcome him as the new leader and suggested that new opportunities for peace may arise. It was tempting to interpret this as a sign of trust in Abbas by the Israeli Prime Minister. However, in the same breath Sharon stated that he was only prepared to enter peace talks on the precondition that Abbas brings an end to violence against Israel.

During secret negotiations and peace talks in South Africa, the ANC made it clear that it was impossible to end the armed struggle as long as its leadership was in prison or in exile. In addition, organisations of the people were banned and there was no agreement on the transfer of power. From the French and American revolutions of the 18th Century to liberation struggles and decolonisation of the 20th Century, it has long been a fundamental right of a people to organise a resistance against its occupiers.

The Palestinian people are trying to liberate themselves just as other peoples in the world have. Israel cannot expect the Palestinians to agree to one-sided measures. And just as in South Africa, it must be remembered that a “people” is often made up of many separate groups with different aspirations. While the ANC knew it was the largest group representing the aspirations of the South African people, it also acknowledged that all groups must play a part in peace negotiations for them to work. Equally, all groups made it clear that a ceasefire would only happen if the South African security apparatus were considerably reduced. In other words, “halting the violence” applied to all parties.

If Israel intends to stick to its precondition that all hostilities of armed Palestinian groups must stop before peace talks take place, it must realise that the same also applies to them, namely ending the occupation of the Palestinian territories and related violence against the Palestinians. Peace talks can only be successful when parties operate on the basis of equality, and therefore one party must be prepared to do the same as what is demanded from the other.

Take the advisory opinion seriously

Rather than continuing to decipher and follow the contradictory messages and half-promises proposed by the so-called “Road Map”, a simple and straightforward approach lies in following international law, as interpreted by the August 2004 advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice. This advisory opinion must be taken seriously.3 Israel must begin by recognising the right of the Palestinian people to self-determination. However, it must also go much further than that.

According to international law, Israel — as the occupying power of the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem — has legal obligations towards the Palestinian people and must comply with international law. The Conventions of International Humanitarian Law are fully binding on Israel and must govern all Israeli actions in the occupied Palestinian territories. Israel’s occupation practices also violate the Conventions of International Human Rights Law.

As Israeli settlements breach international law, Israel must accept that they be withdrawn, and not just in Gaza. This should be done in a dignified way, and not by smashing the infrastructure, as the Portuguese did when they had to leave Mozambique, and as indeed, historically, most retreating armies have done.

Fundamentally, Israel must also accept that construction of the wall in the Occupied Territories and in East Jerusalem is illegal and should stop construction immediately and begin dismantling it. Furthermore, it must accept that destruction of housing and property to construct the wall is also illegal, and Israel is obliged to make reparations for all damage caused by its construction.

If Israel begins to take the advisory opinion seriously, Abbas will be in a position to build trust by convincing Palestinian groups that are organizing acts of resistance against the occupation to refrain from attacks. Without such “good will” on the part of Israel, however, it is unrealistic and foolhardy to expect Abbas to make any such undertakings.

What will it take?

Beyond respect for international law, what concrete steps should be taken in order to open up possibilities for peace negotiations? In the next article in this series, the authors reflect on steps that were taken by both parties to end the conflict in apartheid South Africa, which built trust and laid the groundwork for peace negotiations.

[NEXT]

Adri Nieuwhof and Jeff Handmaker are human rights advocates based in the Netherlands. Bangani Ngeleza is a consultant based in South Africa.

Endnotes

Related Links