The Electronic Intifada 9 January 2004

Listen to the interview here (48:07 mins) [2.1MB, 3GP format, opens in Quicktime or RealPlayer] or read the transcript provided on this page.

What impact do you think the U.S. media has on efforts towards negotiations and peace when CNN and the like declare any time there is Palestinian-perpetrated violence that the peace process is on the brink of failure?

David Hirst: That’s a reflection of the one-sided ness of the American media, which is endemic and has been for a long time. Since is the beginning, vis-a-vis the whole Israeli Palestinian conflict and the reactions of the media to violence from one side or the other, has perhaps typicalized that more than anything else. I also mentioned in my book in this respect, but according to scientific calculations of some American organizations that devote themselves to this, one should mention that, for example, since the beginning of the intifida, it was always the Palestinians who were portrayed as initiating violence and that the Israelis were retaliating for it.

It became so grotesque, especially in the television coverage, that the figures were something like 100 to 8 times that the word retaliation referred to Israelis, 100 times to Israelis 8 times to Palestinians, while in it became clearer and clearer as the intifada went on, it was more the other way around. The Israelis were intiating violence and the Palestinians were retaliating. And yet it persisted like this, so that is a very typical reflection on the way which the American media has covered the intifada.

MCM: How problematic do you find the lack of historical context in news reports on the conflict?

DH: Of course as a journalist myself, I know how difficult it is to inject history into the situation of a given moment - obviously, no article can be a history. But again one finds this problem in the American media more than other Western media, in the sense that, for example, during the intifada, there was a lack of reference to something called the Occupied Territories, especially in much of the television coverage.

This of course might not matter for those of us who are very familiar with the problem, but generally speaking, the television is informing the mass of the public. So when there is an attack by Palestinians on an Israeli position, and there was no description of where that Israeli position was, i.e. in the occupied territories, it sounded as if it was in Israel proper, so again that illustrates a serious shortcoming indeed by, essentially, the American media.

MCM: What kind of editorial pressure do you think journalists from the U.S. who correspond from the Middle East, particularly Israel-Palestine, face that are different from your experience as Middle East correspondent for The Guardian?

DH: I said in my book that I think it’s difficult for me to say I know precisely what kind of pressures are exerted, because by definition pressures are something exerted surreptitiously in certain organizations. But I also said that I think this bias … is less apparent in the day to day coverage by individual correspondents on the spot than it is in the strictly editorial side of newspapers. The commentators, the editorials as such, the official opinions of the newspapers, seems to me that is where the bias primarily lies.

It is fairly notorious, I gather, from one or two colleagues who write for such newspapers as the Wall Street Journal, which is one of the more right-wing and pro-Israeli newspapers in the United States, there is a clear cleavage of what the correspondents write and what the editorial writers say. In other words, if the editorial writers were to derive their point of view from what their correspondents were saying, they would take a different line because what the correspondents say is really very often at odds with what the opinion columns say.

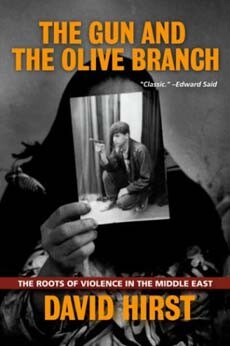

MCM: In the opening pages of the new edition of The Gun and the Olive Branch, you contrast how your book, first published in the U.S. in 1977, was met in the country with what the publisher described as a “resounding and puzzling silence” while a few years later Joan Peters’ academic fraud From Time Immemorial was heralded by the press. Peters’ book, which was republished in 2001, and Alan Dershowitz’s book The Case for Israel, which plagiarizes Peters, enjoy high sales and are not exposed as frauds in the U.S.’ mainstream press. What do you think these books’ popularity point to?

DH: I must say that although being a long time follower of the conflict, I was aware of a general bias in favor of the Israelis on the part of the American media, nonetheless in researching this book it really came as something as a surprise to me just how systematic this bias could be. I found this Joan Peters case perhaps the most startling illustration of this. It’s not my research, of course; I take my information from people who have written about this in the United States itself, but I found this particularly dramatic.

In Britain for example, this book was laughed out of court, it was derided from the very outset, whereas in the United States the whole kind of cultural, political establishment seemed to rally behind it in the most extraordinary, uniform manner. I can only assume that this stems from the extraordinary strength of what I call the dominant orthodoxy the Zionists inspired, that most of the mainstream establishment organs of opinion adhere to or are afraid to contradict. I think the proof seems to be in the pudding; how is it possible, as Edward Said asked, that otherwise intelligent, thoughtful editors could idolize this book the way that they did? That’s the impression one gets.

MCM: Also in the book’s foreward, you discuss Israel’s friends in America, identifying the somewhat paradoxical relationship between Christian fundamentalists and the pro-Israeli lobby, along with the neoconservatives currently serving in the Bush administration. What do you think might disrupt this triple alliance, or do you see it continue to have a stronghold on U.S. policy and media?

DH: I believe at the end of the day there will be a huge bust-up between the United States and its Israeli protege because I do believe that Israel is not an American strategic asset. I think it’s the very reverse. This, sooner or later, will become apparent in a dramatic fashion. But the problem lies in the domestic arena in the United States. Israel is essentially a critical aspect of domestic politics. It’s rooted originally, I would say, in the strength of the Zionist lobby. But that has grown out, fortuitously perhaps, a new and larger force in the shape of the right wing Christian fundamentalists who now, some people would say, are more important than the Israeli Jewish Zionist lobby itself.

It’s very bizarre, because we also know, theologically speaking, these two groups - the Christian right and the Jews - should be, and were in fact, at odds with each other. We know the right wing Christians don’t hold out a very nice fate for the Jews with the coming of the millennium. But all this seems to be swept under the carpet now for pragmatic reasons. In fact … eight years ago the Anti Defamation League produced a denunciation, a formal booklet or pamphlet, of the right wing Christians. But a few years later, it came out with a statement to the effect that, well they are now our friends, even if our motives are different than ours, we’ll forget about the motives, we’ll ignore them for the time being. It’s a very bizarre alliance, but evidently a very powerful one, especially with the President of United States, a man who says he is sympathetic to the evangelicals. I don’t think we will see any break down of this alliance while Bush is in power.

MCM: In an article that was published in The Japan Times in 2002, you argue that Israel has become the U.S.’ own rogue state, and that the game is up regarding the U.S.’ ability to rein in Sharon and prevent him from disrupting the regional order. Do you see any other entities, such as the European Union, the United Nations, or the Arab League, even coming close to disciplining Israel in an effective manner?

DH: It’s clear that one of the issues that divides Israeli and European opinion, and to some extent, European government policy, in these times and since the Bush administration came to power … is America’s treatment of the Arab-Israeli conflict, vis-a-vis Europe’s. I think that the Europeans are likely to grow more hostile to America’s promises on this question the more the Americans align themselves behind Sharon and his policies.

But as we also know, America has always dominated the peacemaking in the Middle East, and continues to do so despite efforts by the Europeans to inject some degree of fairness into it. Even Tony Blair is playing a role in this despite his alliance with the United States in the invasion of Iraq. It is said that the road map to peace was inaugurated in July by President Bush, to some extent in deference to Tony Blair’s concern about the negative impact of the invasion of Iraq on the other great Middle Eastern problem, namely the Arab-Israeli one. It is clear that this European input is not really very effective because, essentially, Bush, though he may be embarrassed by Sharon’s behavior, is not willing to give any great effect to his embarrassment by reining him in, especially of course in an election year.

MCM: If there were trade restrictions implemented by various European states and the countries in the Arab League, do you think that would have any kind of influence on Israeli policy regarding the Palestinians?

DH: I suppose it would. I think there was a [controversy] recently concerning the export of goods from the Occupied Territories, products emanating from Israeli settlements, which were labeled as if they were coming from Israel proper, and this caused considerable alarm in the government quarters in Israel. I’m not sure what the upshot was, but it certainly did worry them. I’m sure that if sanctions of that kind, if they were stepped up incrementally, really would have a great impact on Israeli thinking.

I don’t know how the Israelis would react, but it would certainly be very damaging. Today the Israeli minister of Justice has publicly stated that he thinks that the construction of the so-called apartheid wall risks turning Israel into a pariah state, obviously a sign of greater alarm. So yes, what did eventually happen to South Africa? That’s the parallel that he drew, and economic sanctions would of course stem from the European view that there is a parallel between Israel and South Africa in their treatments of the Arabs.

MCM: In the section of the foreword aptly titled “No End of American Partisanship,” you identify that Israel has used its nuclear arsenal not necessarily to threaten its Arab neighbors but rather as a means to blackmail the U.S., lest Israel use its weapons to completely disrupt the balance, albeit a precarious one, of the region. Do you think Israel’s air strike on Syria this past autumn was a not so subtle reminder by Israel to the U.S. of its capacity to destabilize U.S. interests in the Middle East?

DH: I’m not sure if that was the intention, but that certainly is an impression that it deliberately or inadvertently creates. The basic argument which I make in the last part of the book, when I deal with this question of nuclear weapons, is to say that this Israel which America has, formally speaking, anointed as a strategic asset, and which American politicians sincerely or otherwise regard as such an asset, can easily become a liability. In fact, it can be easily be seen that the Israelis sometimes surreptitiously, or not surreptitiously actually, intimate that they have the ability to be a strategic liability. That is to frighten the Americans with its capacity to disrupt their policies in the region; the capacity, in the final analysis, to destroy American interests in the region.

The most dramatic example of this, of course, is to be found in the nuclear context. I quote a well known Israeli military strategist who himself is quoting the former Israeli Minister of Defense, the late Moshe Dayan, saying that Israel should behave like a mad dog, so that nobody touches it. That kind of mentality has been latent in Israeli strategic thinking from the very outset, from the very beginning of the state. So yes, obviously Israelis don’t want to use their nuclear weapons, nobody wants to use their nuclear weapons, but to have them as a deterrent against those who they may feel threaten them, or against those like the Americans [they fear] might abandon them, precisely because, at some point, Israel is going to be a terrible source of diplomatic and strategic setbacks for the United States.

MCM: You write in The Gun and the Olive Branch that during Begin’s administration of Israel, “The more moderate, the more ‘civilized’ the PLO became, the more this alarmed Begin and his superhawks” because it meant that there could be a long-term solution, something that Likud didn’t want. Do you think that the so-called “targeted killings,” or assassinations, of Palestinians by Israel during lulls of Palestinian violence, which inevitably lead to more suicide bombings, are conscious efforts by the Sharon administration to prevent a long-term solution from occurring?

DH: I certainly think that these targeted assassinations and other things like that were designed to prevent the introduction of a stable cease-fire because a cease-fire would mean that diplomacy would have to start again, and Sharon does not want diplomacy to start again. He’s more comfortable with a situation in which there is no diplomacy because diplomacy means, at the end of the game, declaring your hand, what have you got to offer, what kind of peace do you want or are you prepared to accept. Sharon’s peace is the very antithesis of peace as it is generally understood by almost everybody.

Officially speaking, I’m not now talking about the current administration and the neoconservatives, the Europeans and the Americans share a basic, general orthodox view of what the basis of peace would be - a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza. But his formula, insofar as we know it, became clearer in the last week with the speech that he made to an institution in Tel Aviv concerning the necessity of the Palestinians to come forward after eliminating the infrastructure of terror, to come to the peace process in a serious way. If that didn’t happen, there would be unilateral steps on the Israeli side, and he made it clear that these unilateral steps would involve a disengagement of the Israelis from really a rather small area of Palestine, of the West Bank and Gaza, leaving the Palestinians in charge of something like 42 percent.

So that’s what he means, territorially speaking, by peace, and it’s not even peace - it’s going to be another interim agreement so that he is free to continue with the up-building of greater Israel. So yes, these targeted assassinations are designed to essentially prevent a peace, as the world understands it, from coming to pass, by a dynamic which he sets in motion, a cycle of violence.

MCM: In your book you refer to a 2002 poll that “showed that 46 percent of the population [of Israel] would like to see the ‘transfer’ of the inhabitants of the occupied territories, and 31 percent … [would like to see] that of the Palestinians of Israel proper.” Already Israel has been implementing population transfer since Oslo, but in an incremental fashion so as to keep it off of the international radar. Do you think that population transfer will continue in this incremental way without disruption, or do you think that Sharon will implement a mass transfer of Palestinians, under the guise of fighting terror, after, say, a particularly devastating suicide bombing?

DH: It’s an interesting question. It seems to me clear that a great many Israelis, ideally, would like to see an Arab-free West Bank and Gaza. The statistics seem to show that. But of course, the question is how to implement this, and there was some expectation that Sharon might have engineered a mass expulsion under cover of dramatic events elsewhere, events which might have been generated by the invasion of Iraq, but that didn’t come to pass.

I think it’s difficult to foresee any circumstances that might give him the opportunity to do this. I can’t visualize any circumstances in the foreseeable future. But I’m sure that if they did arise, the temptation to use this as a pretext to engineer mass expulsion will grow greater and greater, so long as there is no settlement before such circumstances arise. Because the problem facing the Israelis, the demographic problem, is really getting worse and worse all the time because of the disparity in birth rates.

But I see the [West Bank] wall as a part of a process of what you call incremental transfer or pressures designed to bring about transfer, because life become so impossible for yet another large group of Palestinians that it will push them into despair to leave. A different kind of incremental pressure has been present ever since 1967. The Israeli ministers have not so surreptitiously advocated it; Moshe Dayan was one of them. But I think that will continue indefinitely. There is always the possibility in some traumatic regional compulsion that the Israelis will do again what they did in 1948 or 1967.

MCM: What changes have you noticed in Palestinian, Arab, and Israeli psychology since you began reporting for The Guardian in 1967? Are there differences in attitudes and identity regarding the conflict from one generation to the next?

DH: The greatest change has probably taken part is to be found among the Palestinians who are essentially the losers of this conflict. When I first started reporting, the Palestinians were all of the opinion that the Israeli state has to be dismantled, and the territory completely liberated. This was formally expressed in the official aims and ambitions of the PLO, the Palestine Liberation Organization, and remained the official position until the late ’70s when a change began to take place.

It was finally crystallized in the 1988 meeting of the Palestine National council, which formally for the first time declared that the Palestinians were ready to accept the two-state solution, and it was further consecrated in the Oslo accords. I think that was the official PLO position, but it’s fair to say that most Palestinians were ready to go along with it. So there’s a fundamental change in the thinking and the attitudes of the Palestinians. And I do believe that if the Israelis had been reasonable, and saw the generous offer that the Palestinians were collectively making, we would have a peace now.

But they were not reasonable, and so I fear there may be a shirt back to the original thinking, the original standpoint among the Palestinians because they were drawing the collective conclusion that peace with this intruder is something impossible to achieve, and there will be [a similar conclusion] in the wider Arab world. So that’s where I see the largest, most general change, in the standpoint of one side of the conflict. It seems to me, as I said in the book, that the Israelis have simply just grown more and more extreme, and that is manifest in the people who run and have run the country since the emergence of the Likud in power in 1977.

MCM: You write in The Gun and the Olive Branch, “Under the guise of forcibly divesting Iraq from its weapons of mass destruction, the United States is seeking to ‘reshape’ the entire Middle East, with this most richly endowed and pivotal of countries as the lynchpin of a whole new, pro-American geopoligical order.” In addition to Iraq, which countries in the region are most vulnerable to U.S. ambitions? Do you see any countries that are allied with the U.S, facing uprisings from within their own borders as a result?

DH: The countries most vulnerable to the Saddam treatment, so to speak, are pretty well known - not much is hidden by the neoconservatives who are the architects of this policy. Syria and Iran are the two most obvious candidates, but the more pro-Israeli of [the neoconservatives] also have their sights on Saudi Arabia, a long standing American ally. Some of them write about six or seven Arab regimes that should go, from Libya, via Egypt, to Syria, Saudi Arabia, and non-Arab Iran. And let’s not forget Yasser Arafat.

MCM: It seems that if such a dramatic shift in power balance occurs, then perhaps some countries that have enjoyed relative stability, i.e. Jordan, would be threatened by unhappiness within their own population.

DH: Well, yes. We’re always asking, we journalists, about the famous “Arab street” which is permanently at odds with their own governments. The level of disillusionment of the Arab people vis-a-vis their own governments, partly because of their own governments’ incompetence in dealing with the Israelis, and their subservience to the Americans, but also for well known domestic reasons. It’s legendary. But this famous Arab street never does seem to rise.

I would hesitate to say that a country like Jordan is more seriously at risk to such an internal explosion than so-called radical regimes like Syria, which is not seen as being very friendly to the United States, or Saudi Arabia. I think at the moment a country like Syria does enjoy a greater standing in the greater Arab public opinion than does a regime like Egypt or the Hashemites in Jordan. But the level of discontent inside Syria, for strictly domestic reasons, is just as great vis-a-vis that regime, as the level of discontent vis-a-vis the Jordanian regime.

They’re all in a sense the same boat, these same regimes, in that they’re all as discredited as each other. I think what’s happened in Iraq has certainly pushed the region towards upheaval, upheaval which would probably becoming anyway because of this deplorable relationship between governments and people in the region, between rulers and ruled, because they’re all sick regimes, and it’s going to happen. But the destabilization process has been expedited, given a huge push, by Iraq.

MCM: What do you think it’s going to take to change for the better the status quo of curfews, checkpoints, and lost lives of Palestinians living under Israeli military occupation the West Bank and Gaza Strip?

DH: I find it difficult to imagine that until there is a final settlement, the Palestinian situation is going to change for the better in a serious way. I don’t think that the intifada is really going to disappear. It may have lulls, but it’s not going to disappear.

I don’t think the Israelis are going to enjoy any significant sense of security until this intifada is over. I really don’t think it’s going to be over until there is a final settlement. I don’t even believe there’s going to be a final settlement unless there is an imposed one from the outside. I just can’t see these two parties agreeing to anything without huge external pressure or intervention because they’ve tried everything. They’re simply not able to accommodate each other. One peace plan after another goes down the drain and there is no real progress.

Maybe the maximum was reached not at Camp David, but at President Clinton’s last desperate effort to achieve an accord just before he gave up his presidency. But that was the maximum and it failed, and under a regime like Sharon’s it’s not possible to imagine any serious peacemaking. So the situation will continue as it is, and I think that there were be more dramatic terrorism than there has been so far. But the situation could go on for a long time like this before some kind of resolution, before some kind of intervention from the outside world.

Related links

Maureen Clare Murphy is an Arts, Music, and Culture correspondent for EI and its sister site eIraq.