Challenge 3 November 2003

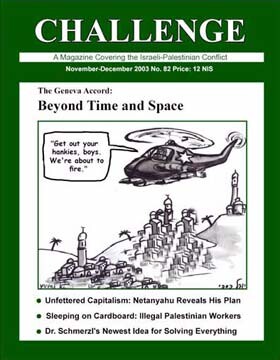

The cover of the current edition of Challenge magazine. To visit Challenge’s website, click here.

The new accord places before the two peoples, for the first time, an idea of the approximate price that each would have to pay in order to gain a peace agreement that the other might perhaps someday be persuaded to live with. It breaks taboos: a few Israelis speak publicly, in detail, about dividing Jerusalem; a few Palestinians adopt a document which, in effect, nullifies the refugees’ right of return. Proponents make the further point that the agreement explodes the myth that Israel has “no partner” for negotiations.

Such claims, we shall see, are questionable. The single definite change is this: the Zionist left (which eleven years ago stepped into the shadow of the Labor Party, enticing the Palestinians into the trap of Oslo), has taken at last an independent stand, its most radical ever, showing how far it is willing to go in a future agreement with the Palestinians.

As to the Accord itself, we shall focus on two questions. How far exactly are the signers willing to go? How relevant is the document?

Breakthroughs occurred on three fronts.

1) Territory - To appearances, the Israeli side acceded to the principle of not taking land, although it did so by trade-offs: that is, it adopted the principle that for every acre Israel annexes beyond the border of June 4, 1967, it will compensate the Palestinians with an acre of Israeli territory elsewhere. The land annexed to Israel will consist of certain Jewish settlements. All in all, it will amount to about 2.5% of the West Bank.

2) Jerusalem - The sides adopted the principle that Arab areas would pass to Palestinian sovereignty, Jewish to Israeli. In the Old City, the Jewish Quarter and the Western Wall would become part of Israel, the other three quarters part of Palestine – with heavy reliance on international observers.

3) Refugees - The Palestinians did not explicitly forgo the right of return. They were not asked to do so. The Accord stipulates, however, an end to all past claims. It provides that the number of refugees allowed to return will depend on Israel’s agreement.

This may look promising, but on reflection we cannot but wonder about the identity of those who play the Israeli side in these fictitious negotiations. Are they the left ? Surely, the left ought to be the ally of the Palestinian people, working with it to change the present reality. But these, we must remember, are the Zionist left (an oxymoron).

For the agreement takes Israeli supremacy as axiomatic. We see this in the fact that the settlements near Jerusalem, including the Jewish neighborhoods built after 1967, will be recognized as part of Israel, and likewise the Etzion Bloc between Jerusalem and Hebron. Yet why (on the basis of what principle) should French Hill (the first post-1967 Jerusalem neighborhood) or Ma’aleh Adumim (a Jerusalem suburb in the West Bank) be annexed to Israel? As in the case of settlements like Ariel and Kiryat Arba, they sit on lands that Israel conquered; they are “facts” that Israel “created”. Why should leftists, even Zionist leftists, start from a position that accepts such “facts”?

Or to take another instance: Palestine will have no army. It will depend for security on massive international forces, relying on the kindness of strangers. It was far from the minds of the Zionist-leftist negotiators to allow parity on this point.

Speaking of parity, the Geneva Accord does not address the economic dis parity between Israel and Palestine or between Israel and the wider Arab world. This disparity will be the central factor in the coming struggle between haves and have-nots, where Israel stands exposed as an anomalous extension of the first world into the third. No wonder the Zionist-leftists want Palestine demilitarized !

In the current geopolitical realities of the Middle East, the Palestine of the Geneva Accord will be a wingless chicken, poor and dependent. As Jaffa to Tel Aviv.

Oour main criticism of the Geneva Accord pertains, however, not to its content but rather to the context in which it has been published. It lacks all relation to time and space. Its spokespersons admit that the document is incomplete (e.g., they have not completed the articles on water or the economy), because there was an urgent need to publish it.

The urgency derives from political dividends the framers hope to gain, given the vacuum left by Abu Mazen’s resignation and the de facto disintegration of the Road Map. That vacuum finds Israel today in one of its worst and ugliest moments. America’s Iraq adventure has not worked out. Israel’s gamble on George W. Bush has only increased its isolation. It has no guiding political concept.

The blows it rains on the Palestinians look increasingly futile, a mere kicking-out in frustration. The economy is in atrophy: people sink into unemployment while welfare benefits are cut. Ariel Sharon still has public support, but his government has lost its moral standing both in relation to the Palestinians and to its own citizens.

Into this vacuum step the Zionist-leftists with a virtual peace plan. If this had a chance in the current reality, then welcome. If its signers would present it as the basic program for a future social-democratic party, then too welcome. It would be their right to tell voters how they think the conflict ought to be resolved. They could then put the program to a test at the ballot box. Instead they make somersaults in the air without sticking a toe into muddy reality. In short, the appearance of the document at this time has the air of a publicity stunt, rather than of a proposal capable of realization.

The Geneva Accord is supposed to present each side with a realistic view of what peace will cost, but its effect is rather to obfuscate reality.

1) In the Palestinian arena: anyone to talk with?

The Palestinian Authority teeters above the void. On November 4, PM Ahmed Qureia (Abu Ala) will decide whether to continue in his post. Unless Arafat gives him sufficient control of the security forces, and unless Israel restrains its attacks on Palestinians, he will likely quit. It is an open secret that the rest of the cabinet may resign collectively, turning the keys over to the Occupier.

In MIFTAH (the Palestinian Initiative for the Promotion of Global Dialogue and Democracy), an unusual article appeared on October 18 under the title “Chaos”, including these words: “Instead of dismantling the occupation, we are dismantling our institutions, our people. Ultimately, we will end up with a fragmented people and no law and order, but still determined to resist. In other words, chaos.”

The Palestinians no longer know who is governing them: Arafat, Qureia, roving gangs, Israel? Amid the disorder, how can Beilin and his Geneva associates tell the Israeli public, “There is a partner, someone to talk with”…?

The Accord has encountered opposition in the upper Palestinian echelon. Nabil Sha’at, a moderate toward Israel and America, gave an interview to Al-Ayyam on October 25, criticizing the formulation concerning refugees. He also opposes the excessive use of international forces, claiming that the Palestinians will allow them only on the borders.

2) In the Israeli arena: danger of civil war

The Accord requires the dismantling of most Jewish settlements while assuming the basic framework that we have, i.e. the PA on one side and a Likud or Labor government on the other. But even Labor has always backed down before the settlers - and not by chance. Any Israeli government that tries to evacuate settlers invites civil war.

The Geneva Accord thus gives an impression that is divorced from reality. Those who enthusiastically leap on the bandwagon will find themselves disappointed, as with Oslo, after wasting huge amounts of energy and time. As a condition for the dismantling of settlements, there would have to be a major change in the global alignment of forces, beyond the limited framework assumed at Geneva.

We should mention in this regard that Geneva architect Yossi Beilin has no political base. In the last Labor primaries, after the debacle of Camp David, he failed to win a realistic place on the list. One wonders: suppose Beilin and the other signers had won and were part of government; would they then dare offer this Accord to the public? Without governmental responsibility it is easy to float utopias.

3) In the international arena

The Bush Administration includes enthusiastic supporters of Ariel Sharon. They seek to crush all opposition from the Palestinian people: “No rewards for violence!” Only thus, they believe, can peace be achieved. Their approach to the Palestinian question is cut from the same cloth as their attitude toward all the peoples of the Middle East. The Palestinians and Iraqis are currently under treatment, Syria and Iran in the pipeline. The Geneva Accord does not fit this approach. For one thing, it does not address the issue of terrorism. The Bush Administration insists on the Road Map, which freezes all negotiations until the Palestinian side puts down the armed opposition within.

In an article entitled “Long is the Road to Geneva” (Yediot Aharonot, October 17), Nahum Barnea describes the difficulty of connecting the Accord to reality. The signers, he writes, “completed what they had left unfinished (at Taba in January 2001 – Ed.). As if time had come to a standstill. As if Clinton were still in the White House and the left were still governing Israel and Arafat were a leader like others. As if three years of mutual killing had not changed anything in the hearts of Israelis or Palestinians. As if agreements between peoples could be made in a vacuum, sans emotions, sans politics, sans history.”

In the end, the Geneva Accord will be rejected not because of what it includes or omits, but for another reason altogether: In order that trust should develop between the two peoples, the Israeli left will have to give up the precondition of Israeli supremacy. It will have to stop viewing the Middle East through the prism of American imperialism. It will need to look rather through the prism of the worldwide forces opposing that imperialism.

How close is the left to such a change? In Al-Ayyam (October 25), Yossi Beilin writes that the Geneva Accord is not intended to supplant the Road Map. On the contrary, he said, it completes it.

The flirtation with America continues.

Related Links

This editorial first appeared in Challenge magazine, Issue #82, November-December 2003.