The Forward 19 February 2003

Israel is seeking to mobilize American and Jewish support for a diplomatic battle with Belgium after the Belgian Supreme Court upheld a law that would allow the prosecution of Israeli officials — including, eventually, Prime Minister Sharon — for war crimes related to their role in the Sabra and Shatila massacre two decades ago.

Israeli officials responded furiously to the decision, with President Moshe Katsav firing off a letter to the Belgian king and Foreign Minister Benjamin Netanyahu branding the ruling a “blood libel” and recalling Israel’s new ambassador to Belgium.

Israeli officials also seized on the trans-Atlantic row over the showdown in Iraq, stressing that the Belgian court ruling had come just after Belgium’s decision to stand with France and Germany in opposing the dispatching of NATO military aid to Turkey.

“The day of reckoning has come and the responsibility for the entire trans- Atlantic relation relies on Belgium,” Nimrod Barkan, director of world Jewish affairs at the Israeli Foreign Ministry, told the Forward in a briefing last week in New York. “The Belgian government is embarrassed, and it doesn’t want a political war with the U.S.”

Israeli officials said they hoped Americans would use direct and indirect avenues of communication with Belgium to press home the damage to its relationship with the United States should Belgian authorities attempt to arrest Israelis in connection with the case. They declined to be specific as to what sorts of pressure were being sought.

Patrick Herman, deputy spokesman for the Belgian Foreign Ministry, told the Forward that the government was not allowed to interfere with the independent judiciary system and insisted that the ruling was not anti-Israel.

“We have 29 similar cases and it just happened that the Sharon one was the one that was sent to the Supreme Court for review,” he said.

He conceded that the timing was “awkward.” The ruling was issued just before Belgium’s Prime Minister Guy Verhofstadt came to the United States on a visit aimed partly at drumming up investment and partly at calming American anger over Belgium’s decision to back France and Germany in the NATO row.

Herman said that while his country was saddened by the “unjust” attacks coming from Israel, he still hoped the “excellent” relationship between both countries could be reestablished as soon as possible. He admitted that the improvement may take time, given the harsh words and the recall of the Israeli ambassador to Belgium, Yehudi Kenar, just before he was to present his credentials.

Israeli officials were quick to cast the decision as the perfect illustration of the excesses of international justice that the Bush administration has been repeatedly denouncing, leading it to retreat from the International Criminal Court last year. Israel withdrew its initial support for the ICC for similar reasons.

A senior Israeli official said Israel had approached Justice Department officials and members of Congress, just as Belgium’s prime minister was visiting the United States, to warn them that “they could be next” on Belgium’s list.

State Department officials were reportedly sympathetic to the Israeli complaint. “We continue to be concerned because of the extra-territorial reach of the law and the possibility of politically motivated prosecution,” said Amanda Batt, a spokeswoman for the State Department. “We made our concerns known to the Belgian government.”

By contrast, human rights groups hailed the decision as another stepping stone in the era of international justice heralded a few years ago when former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet was arrested in Great Britain on a Spanish warrant. Pinochet finally escaped extradition to Spain after a long standoff because of alleged health problems.

The high-profile Sharon case reinvigorates a little-used 1993 Belgian “universal jurisdiction” law that permits lawsuits to be filed in Belgian courts for war crimes, crimes against humanity, torture and genocide regardless of the time and place where the crimes took place and regardless of any national or geographical link to Belgium by the plaintiffs or the accused.

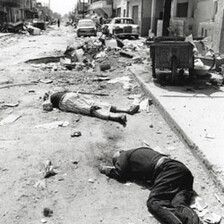

The case against Sharon was brought two years ago by a group of Lebanese citizens [incorrect; of the 23 plaintiffs, more than 75% are stateless Palestinian refugees — lki], charging him with war crimes in connection with his indirect role in the 1982 massacre of at least 800 Palestinians by Phalangist troops in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps outside Beirut while the camps were under Israeli control. Sharon was found “indirectly responsible” for the massacre by an Israeli judicial commission [incorrect: the commission was not a judicial one; it lacked any binding force, as it was only investigative] in 1983, and was barred for a time from holding high office. [Sharon actually remained in Begin’s cabinet as “minister without portfolio”.]

Last June, a Belgian appeals court ruled that Sharon could not be tried in Belgium because he was not physically present in the country. The Supreme Court reversed that ruling last week. The ruling acknowledged diplomatic immunity only for serving heads of state or ministers.

Based on the ruling, Belgian prosecutors could now open proceedings against other Israelis allegedly involved in the massacre, including former Israeli army chief of staff Rafael Eitan and current Defense Ministry Director General Amos Yaron, who was the Israeli army commander in Beirut at the time. Proceedings against Sharon may be opened after he completes his term as prime minister.

Beyond the possibility of arrest on Belgian soil, Israeli officials are worried about possible extradition demands from other European states. Israel has extradition treaties with most European countries, and all members of the European Union have conventions requiring that an extradition request by one be considered by others.

“We expect the Belgian government to act politically to make sure the law is changed in order to prevent the deterioration of the relationship between Belgium and Israel,” Barkan said.

Herman, the Belgian official, explained that after the lower court decision the legislators decided to revise the 1993 law, amending it slightly in response to some of the criticisms directed against it.

The new version of the law — already approved by the Belgian Senate and expected to be adopted soon by the chamber of deputies — would grant immunity to serving heads of state or government, as well as ministers.

It would also acknowledge the preeminence of the ICC, which will have priority in prosecution of crimes committed after its establishment on July 1, 2002. Finally, the law creates a “filter” against abusive lawsuits by granting the prosecutors’ office the option of rejecting complaints if they are deemed unfounded or politically motivated. Herman said the idea was to ensure that cases brought have some geographical linkage to Belgium.

Herman noted that the Belgian law has also served as a basis for complaints against other foreign leaders, including Yasser Arafat. A Belgian Jew who was hurt in a 1982 bombing attack on a Brussels synagogue for which the Palestine Liberation Organization took responsibility is planning to press charges against the chairman of the Palestinian Authority.

But Israeli officials appeared unwilling to play tit-for-tat and blasted the “unbelievable expansion of international jurisdiction,” in the words of a senior Israeli official.

Belgium is not the only country to have enshrined elements of universal jurisdiction in its laws. Both the United States and Israel have legal mechanisms that allow foreign acts to be prosecuted in their courts.

The Alien Torts Act allows foreigners to sue in United States federal court if acts were committed against them in violation of the law of nations or an American treaty. It was used by a group of Bosnians against Serb leader Radovan Karadzic for crimes committed in the Balkans. However, it involves civil suits while the Belgian law deals with criminal law.

In Israel, the Knesset passed an amendment to the Penal Code in 1995 that is almost identical to Belgium’s 1993 law, Yoram Shahar, an expert with the Interdisciplinary Center in Herzliya, told The Jerusalem Post. Israel also passed legislation making it responsible for the protection of every Jew around the world, whether or not such protection is requested. According to this law, anyone committing a crime against a Jew anywhere in the world breaks Israeli law and is liable to punishment by the Jewish state, Shahar said.

Ironically, Israel may have been the pioneer among nations in forcefully applying universal jurisdiction. In 1960, Israeli agents kidnapped the Nazi official Adolf Eichmann in Argentina, bringing him to Jerusalem to be tried for crimes against humanity committed in Europe during the 1940s, before Israel achieved statehood. He was hanged in 1962.