The Electronic Intifada 17 September 2002

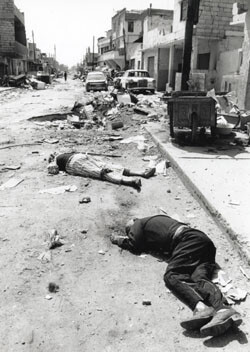

The dead lie in the streets of Sabra and Shatila (UNRWA)

Israeli Defense Force (IDF) soldiers, commanded by General Ariel Sharon and assisted by Generals Rafael Eitan and Amos Yaron, had prevented anyone from entering or leaving the camp — anyone, that was, but Israeli-backed, -armed, and -supplied Phalangist militiamen, infamous for their murderous hatred of Palestinians. At night, IDF soldiers had launched illumination flares into the sky to assist these militiamen in their gruesome tasks, the results of which would appall the world by the evening of that September Saturday two decades ago.

Yet even before the journalists, diplomats, Red Cross personnel and others had entered the camps that morning, their worst fears were confirmed by the nauseating smell of putrefying flesh and the audible drone of feasting flies, the only sound to break the stifling silence before the anguished screams of survivors shattered the air. Hardened journalists vomited. Grown men fainted. Seasoned Red Cross representatives were dazed.

“I divide my life into before and after Sabra and Shatila,” said Elias, a former Red Cross volunteer with whom I worked in Lebanon. “I was not the same person after I saw the severed bodies of babies and the corpses of women with their stomachs ripped open. For weeks, I imagined I could still smell all those bodies stinking in the heat of that morning. It completely altered my view of human nature.”

Only seventeen at the time, Elias was among the youngest of those to discover one of the worst atrocities of the post-World War II era in the refugee camps on September 18, 1982. Now approaching his forties, he will never forget that date or its significance.

Unfortunately, many people do not know, let alone remember, that the Sabra and Shatila massacres occurred.

Some, upon learning that at least 1,500 innocent Lebanese and Palestinian civilians were tortured, raped, mutilated and then slaughtered in a two-day orgy of murder and mayhem, after a summer in which the invading Israeli army committed numerous war crimes resulting in the deaths of over 15,000 civilians, simply shrug, as if to say “Oh, well, what can one do? That’s the Middle East, after all. Things like that happen over there all the time.”

But massacres don’t “just happen.” They are not natural disasters, like earthquakes, tornadoes, or tidal waves. Massacres require thought, planning, and coordination. Massacres arise from calculated strategies and the cunning manipulation of emotions, facts, and rationales. They require a particular set of interlocking social roles and a specific pattern of behaviors. Every massacre has its own political organization, propped up by a set of motivating beliefs and legitimating ideologies.

Massacres don’t erupt spontaneously, like barroom brawls. When an army is involved—as was clearly the case 20 years ago in Beirut, a divided city under Israeli military occupation—massacres also require a chain of command. Orders are given, tanks are deployed, papers are checked and approved, passage is denied, roads are blocked, exits are sealed, flares are launched, soldiers are transported across demarcation lines, murderers are provisioned, mass graves are dug, corpses are concealed, people are disappeared, and then stories are spun, excuses are offered, and—always— facts are denied. The first casualty of every war and the last casualty of every massacre is the same: the truth.

Under international law, specifically the IV Geneva Conventions, command responsibility for war crimes ultimately rests upon the shoulders of the highest-ranking military officers present. In the case of the Sabra and Shatila massacres, that person was and remains General Ariel Sharon. The fact that, 20 years later, Sharon is a sitting head of state enjoying the perquisites of power and prestige while the dead of Sabra and Shatila lie forgotten in unmarked graves should be cause for widespread alarm and outrage. The absence of such is sinister; it comprises evidence of other, ongoing and metaphorical, murders.

The Dangers of Impunity

Massacres have authors; they are crimes that must be investigated and prosecuted. For the bereaved, massacres never end until justice is done. Every day since that horrific Saturday in 1982 has been September 18th over and over again for the survivors of Sabra and Shatila. To forget a massacre is to kill the dead a second time; to forget the dead is to condone the crime and to excuse the killers. And the dead of Sabra and Shatila have been killed many, many times. Every time another anniversary passed and no one marked it, every time garbage desecrated the mass grave site, every time the Lebanese authorities refused to investigate or prosecute the crimes, not only the dead, but also the tormented survivors, were murdered again and again.

Today’s 20th anniversary of the massacres goes unmentioned in major newspapers. The significance of this date will not be commented upon by news anchors. The killers are now “honorable men” and masters of the dark arts of PR spin. They are well-protected by friends in high places in government and media.

Every time Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, who, according to an official Israeli commission of inquiry “bears personal responsibility” for the massacres, is warmly welcomed in Western capitals and heralded as a “man of peace,” the truth is murdered once more. This is how impunity flourishes, how laws are rendered meaningless, and how the delicate fabric of human social and political affairs gradually erodes.

Continued impunity for the Sabra and Shatila massacres is not only morally reprehensible and psychologically unbearable, but also politically dangerous because of the precedent it sets and the hearts and minds it poisons. He who is denied justice will seek revenge. The evil of a crime condoned festers and spreads, eventually touching others, even miles away and decades later.

An Agonizing Anniversary

A woman cries at the loss of relatives (UNRWA)

The Geneva Conventions specifically state that all signatories to the convention have not only the right but indeed the duty to either prosecute or extradite individuals guilty of war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide. In 1993, the Belgian Parliament formally incorporated the principle of Universal Jurisdiction into Belgium’s criminal code, thereby enabling Belgian courts to hear war crimes cases having no connection to Belgium.

Despite careful documentation and extensive testimonies, despite the consistent support of the Brussels Attorney-General for the arguments presented by the massacre survivors, not those of the lawyers representing the accused, during the pre-trial hearing; and despite new evidence further implicating IDF personnel in the massacres as well as in the disappearance of hundreds of men and boys in the immediate aftermath of the killings, a Belgian Appeals Court threw the case out last June on an absurd technicality: The case could not proceed to trial because the accused were “not present on Belgian soil.”

International legal specialists, no less than Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, noted that this ruling made a mockery of the principle of universal jurisdiction for war crimes and crimes against humanity. Yet another murder has now emanated from the Sabra and Shatila massacres: the murder of popular faith in the principles, processes, and efficacy of international law.

With this decision by a Belgian Appeals Court, the consequences of the crimes committed twenty years ago in Beirut took on new and disturbing international dimensions. The massacres at Sabra and Shatila are no longer simply the bloodiest chapter in the Arab-Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but rather, a glaring reminder and a disturbing proof of the international community’s failure to apply international law fairly and consistently.

Another Attempt at Justice?

Next month, the Belgian Parliament, at the urging of a broad-based coalition of NGOs and individuals representing a diversity of political viewpoints, is expected to pass a new item of interpretive legislation that will salvage the country’s Universal Jurisdiction law and will clarify that accused parties need not be present on Belgian soil for a case to proceed to trial. Should this proposed legislation pass, it will render the Sabra and Shatila massacre survivors’ appeal to the Belgian Supreme Court unnecessary, enabling them to launch another attempt at justice in Belgium for the 1982 massacres in Beirut.

After twenty years of unimaginable anguish, the survivors of Sabra and Shatila are still hoping to attain justice, to lay their dead to rest in peace, and to begin to live again. But justice, like a massacre, does not just happen. Considerable coordination, effort, patience, and skill will be required before the survivors can finally turn the page on the black date of September 18th.

Related links:

Ali Abunimah, The Electronic Intifada, 18 September 2002.