The Independent 4 February 2003

The success of Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid On Earth has focused attention on the “graphic novel”. These extended narratives eschew fights in tights to use the techniques of comics to tell stories far removed from run-of-the-mill stuff.

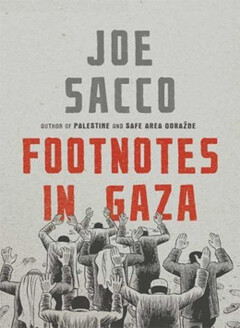

Now, from the publisher of Jimmy Corrigan, comes Palestine, a 285-page work of “graphic reportage” by the Maltese-born, US-raised cartoonist Joe Sacco. In 1991-2, Sacco, having “heard nothing but the Israeli side”, toured the occupied territories, seeking to immerse himself in Palestinian existence. The fruit of his labours emerged as a mini-series of nine comics, now a single set with an introduction by one of Sacco’s primary influences, Edward Said.

Sacco is formidably talented. A meticulous reporter, he scrupulously interprets the testimonies of dozens of victims of the Israeli regime into cartoon form. He is also a gifted artist whose richly nuanced drawings tread a delicate path between cartoonishness and naturalism. His layouts shift in style to match the material: stories told to him emerge in symmetrical panel grids, while incidents in which he is involved, or engage his emotions, are rendered in a far looser style, in which images and captions slide across the page.

It’s a powerful piece of work; yet not without flaws. Few of his Palestinian interviewees emerge as “characters”: the same voice seems to issue from each. By contrast, the Israelis – much as Sacco appears to dislike them – come alive, very possibly because the types they represent are far more familiar to the author.

That leaves Sacco himself as the main character, as well as the source of the book’s leavening of humour. The normal-looking Sacco in the author photograph bears only a passing resemblance to the chin-free, liver-lipped caricature (whom we’ll call “Sacco”) interviewing Palestinians and fourth-walling the reader with self-deprecating commentary. “My comics blockbuster depends on conflict; peace won’t pay the rent,” he tells us.

Comics imply a strong narrative strand. Yet the only narrative Sacco offers is his pilgrimage from camp to occupied village. We find ourselves bogged down in a morass of horrors, from appalling atrocities to the pettiest humiliation, with no end in sight for any character except “Sacco”. He can, after all, simply leave.

When he fetches up in Tel Aviv and starts chatting to Israeli locals, they tell him they just want a normal life. But everything Sacco has shown demonstrates the impossibility of any Palestinian leading anything recognisable as that. Intriguingly, the most cogent summary comes from an Israeli, who tells “Sacco”: “I don’t think peace is about whether there should be one state or two… The point is whether two peoples can live side by side as equals.” There is no narrative closure because the story has not ended, and shows no sign of doing so this side of utter cataclysm.

“Sacco” tells us that “no one who knows what he’s come here looking for leaves without it”. Except, of course, those who arrive seeking credible grounds for optimism concerning a just and lasting peace. Next year in Jerusalem? Only in dreams. And dreams, in occupied Palestine, are in very short supply.