Silwan 11 June 2005

The houses slated for demolition in the Al-Bustan neighbourhood of Silwan. (ICAHD)

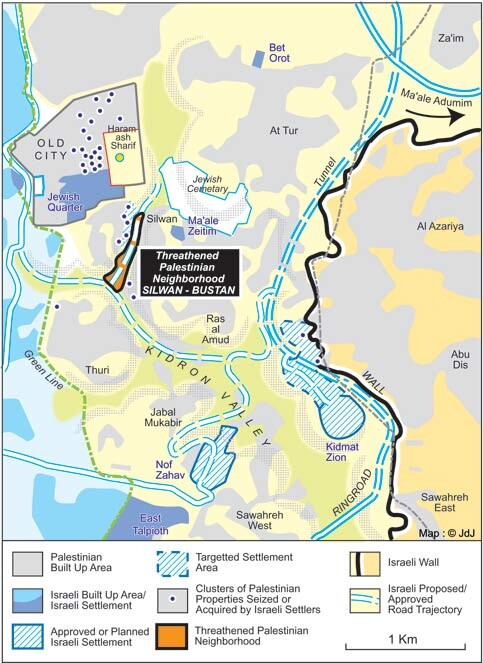

June 8, 2005, Al Bustan, Silwan - We are in the city of David, literally—the oldest part of Jerusalem, below the Temple Mount, not far from the Siloam Tunnel carved in the living rock, almost three millennia ago, by King Hezekiah. Today they call it Silwan: some 50,000 Palestinian Jerusalemites live here, nearly all with blue Jerusalem identity-cards. A few days ago the municipality stuck demolition notices on 88 houses in this neighborhood; some 1000 innocent people are about to lose everything. The ostensible rationale is the creation of an archaeological park in the heart of this Arab quarter. The truth, of course, is very different: this is the creation of another Jewish island in East Jerusalem, a new settlement carved by brute coercion on this densely inhabited slope. And it is probably only the beginning—once the wedge is inserted, they will widen it and connect it to other pockets of Jewish settlers to the north and south and east (Jabal Mukabber, for example, or the ugly monstrosity of Har Homa). The goal is to cut the organic, continuous links among existing Palestinian communities—to “Judaize” and strangle the eastern reaches of the city through settlement, land confiscation, the demolition of houses, state terror and massive military control.

You have to imagine what it feels like to wake up one morning in your own house, the house your grandfather built long before the state of Israel existed, and to find the official notice on the wall. Your home, where you have lived your life, is soon to be destroyed; you and your children will be refugees. It must seem unreal; a house is so stolid and enduring a presence, a thing of mortar and stone as well as intimate refuge. Now the intimacy has been violated; you are threatened, afraid, exposed. A long line of condemned homes stretches all the way up the hill, toward the wall of the old city. In the protest tent where we have come to plan the next moves, a large-scale aerial photograph is pinned to the wall, each of the 88 buildings circled and numbered. Abed points to number 9, his grandmother’s home: the man who built it, her grandfather, died 100 years ago, so the house goes back to the 19th century, Turkish times. Anywhere else it would be preserved as a historic monument, but in Israel-Palestine such considerations are irrelevant; Israel, or Sharon, wants this plot of land, like all the rest.

Can a house be executed as if it were a criminal? What tribunal has tried these homes and found them guilty? What would they have pleaded in their defense? Eloquent placards hang from the walls of the tent, in Arabic, Hebrew, and English: “Where will 1500 people go?” “We pay our taxes to the municipality and what we get is demolition orders.” “Why are they pushing us into the abyss?” “How can we educate for peace when they are destroying our homes?” “No to the confiscation of lands.” “We will not give in.” And, most poignantly and simply: “Please save me” and “Why me?”

I look around at the hills, heavy with the lovely stone buildings of Jerusalem. There isn’t much room; the houses climb vertically with hardly any space between. Children are running in the narrow street outside the tent. Men and women wander in and out, some peering curiously at the strange delegation of some dozens of Israelis who have come to see with their own eyes, to try to help. It is late afternoon, the sun still very hot. Some ten Palestinian women sit clustered on one side of the tent, many with covered heads and long dark dresses. There is a table at the back, spread with petitions and maps; Abed, Muhammad, and a few other men stand behind it, eager to tell us their story.

First Amiel introduces us: we are from Ta’ayush, committed to what the name means—Arab-Jewish coexistence. He explains how we work, cites some of our successes; we will gladly join the struggle here. A young woman, dressed in the modern mode, is the first to respond. She speaks a lucid, forceful Arabic; Khulud translates into Hebrew for the benefit of the guests. She welcomes us, but she is skeptical: What kind of ta’ayush is possible in the shadow of this injustice? What will these mothers tell their children who will see their homes destroyed by Israeli bulldozers? Do we expect them to grow up wanting peace? All that these families are asking is for fairness, a just peace; they want two states, living side by side, and an end to the eternal nightmare. Why should they be forbidden, as they are, to build on their own land? Why do the Jews come to rob them of lands and homes? Why do they forge documents of ownership, and how can the state stand behind the Ateret Cohanim—the most nefarious and unscrupulous of the settlers, who have already taken over buildings in Silwan? The people of the neighborhood pay their taxes, they belong to this city, yet the city gives them nothing, no services—and now comes to destroy them in their own homes. Very angry, articulate, she thanks us for coming to see.

New Israeli Settlement Expansion in and around the Old City of Jerusalem

It has not been easy, we learn later, for these women to agree to our visit. They want nothing to do with Israelis, not even with those who are prepared to stand with them against the government and the army. Somehow the men—all of them veterans of long years of imprisonment by the Israelis for mostly trivial offenses, such as throwing stones at the soldiers during the first Intifada, in the late 1980’s—persuaded them that we could be of use. Now it is the men’s turn to speak. First Muhammad, in a husky Arabic: Here, in al-Bustan, in Silwan, Palestinian houses are routinely destroyed. The city will never issue building permits to Arabs; families keep growing; eventually, in desperation, they build “illegally.” Then the city tears down the house and fines the owners, sometimes enormous sums. One house on this street has been demolished and rebuilt three times. They love their neighborhood: “People say that there is a jannah, a Garden of Eden, in Allah’s heaven, a place of water and green trees; but for us there is only one jannah, and that is Silwan.”

Abed chooses to speak in Hebrew, which he commands with consummate grace. He is a graduate of the finest language school in Israel—nine years in prison. He had plenty of time to polish his skills; he would read every word in the Hebrew papers, even the death notices, and he also acquired perfect English and passable French. There is spice in all his sentences. “We, in Silwan, have two mothers: the Palestinian Authority, which has turned its back on us, and our evil stepmother, the Jerusalem municipality, which is at war with us, a low-level war. They lie to us all the time; they claim we don’t live here, that we came here from Hebron; they say they have to thin out the urban core lest a Tsunami wreak havoc. Has there ever been a Tsunami in Jerusalem?” He says his heart is full of resentment against the Israeli left: there was never anything to hope for from the right, they are as they are, but why is the left—their true partner—so silent and complicit? They have stopped watching television, they never see the news, for the pain is too great. Yesterday the Minister of Tourism came to Silwan in his elegant Volvo, surrounded by soldiers with weapons drawn; he wanted to inspect some ruins. Abed came close enough to say to him: “Instead of visiting these ruins you should visit the ones that you are about to create out of our homes.” He speaks of despair; they have no recourse, catastrophe is upon them; they are not afraid, but they may reach the point of throwing themselves and their children under the bulldozers when they begin their attack.

As he speaks, I stare at the faces of the Palestinian women, many of them old. Mediterranean faces—we could be in a village in Greece or Morocco— weather-worn, eroded by life; they seem to me bewildered, unable to contain the immensity of what has happened. It is as if they had wandered into a story that makes no sense, a story without end or exit, without hope. Watching them in their helplessness, I, too, cannot contain my grief and fury. I rage inwardly, bitter and anguished, wanting only the privilege of facing the bulldozers together with these families; no, also wanting them to know that I understand.

We consult among ourselves. On balance, there is a good chance we can save these houses—by creating public awareness in Israel, through the courts, by galvanizing an international response. We will bring the press, we will plan a joint workday with some hundreds of volunteers; together with the people of Silwan, we will clean and paint and adorn the condemned houses. We will join them in their march next week from this street to the municipality building downtown. If the police try to stop us with their usual methods, tear gas, clubs, arrests, so much the better—it will make the evening news. We have done it many times by now, we are weary from fighting this government house by house and street by street, but we will not give in. Perhaps this is a case we can win.

Chatting afterwards, Abed is amused to discover I teach at the University. He used to work there, caring for the lawns and gardens, until they discovered he had been in prison; they fired him immediately, and now he cannot even visit—he is not allowed to enter the campus. “Give the flowers my regards.” He describes being summoned recently to see Ophir, the Internal Security (mukhabbarat) operative in charge of Silwan. One day his cell-phone rang, and Ophir was on the other end; how did he get the number? But then Ophir claims to know everything that happens in the neighborhood. He warned Abed that he had his eye on him all day long, even knows when he sleeps with his wife. Still, Abed is clearly not cowed; there is a certain self-assurance, an insouciance; and he is eager to work with us.

Of the 1500 shortly to be dispossessed, a majority are children. Muhammad wants to have a day of the children; let them color and paint what they are feeling, let the television show their pictures to the world. Who would have the heart to hurt these children? He can’t believe the government intends to do it. He can’t accept the awful injustice, zulm, though he gives it its true name. He asks my name, I tell him: David, Da’ud. His face flowers into a vast, craggy smile: “Da’ud, King David, he was from here—he was a Silwani.” And for one brief moment the entire mad overlay of identities and claims, bulldozers, houses, Jews, Palestinians, their flags, their postage stamps, the guns, the wickedness of power, all of it falls away before this simple, undeniable fact: whoever he was, if he ever was, King David was a Silwani. Maybe that is all that matters. He would certainly be astounded, also horrified, to see what one party of his children was doing to another, in the name of the all-consuming absurdity of the nation state. This David was, they say, a poet. Muhammad, still smiling, watches me as I think this through. But there is more: Ayyub, the prophet Job, was also here; his well, Bir Ayyub, is just around the corner. So Job, he whose pain was beyond bearing, was also a Silwani. No wonder. It seems to fit the terrain, the grey dust, the dying summer sun, the dark tent, the wrinkled faces of the women. But Job was lucky, after a fashion. After enduring, after refraining from cursing an enigmatic God, he received a whole new set of children, herds of cattle, wealth; what is more, God was stirred to speak to him, not exactly to explain, but at least to recite the magnificent Chapter 38. (He too was once a poet). Today’s Silwanis face a different riddle, perhaps no less intractable, although their suffering has a cause and a rationale—that of deliberate, systemic, remorseless human malice, cruelty and greed. It doesn’t come from any god, although the cry of the innocent is the same: “Why me?”

Professor David Shulman is a member of Taayush/Hacampus-lo-shotek (Students and Faculty against the Occupation). This article was first published in Occupation magazine.

Related Links