The Electronic Intifada 23 July 2010

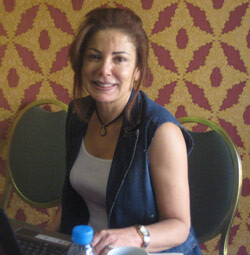

Samar Hajj (Mona Alami/IPS)

“We were all drawn to the project … united by a feeling of stark injustice,” says Samar Hajj, one of the organizers of the Maryam, which is named after the mother of Christ.

Israel’s siege began in 2006 after Hamas won Palestinian legislative elections in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. Its watertight blockade has been maintained with Egypt’s help, since Hamas sought control of the territory in 2007. It has resulted in crippling shortages, making daily life difficult in Gaza.

On 31 May, Israeli forces attacked Mavi Marmara, a Turkish humanitarian aid vessel bringing aid to Gaza, killing nine Turkish activists — one a US citizen — on board. After the attack, which sparked a wave of global condemnation of Israel, Hajj gathered to protest against Israel in downtown Beirut with 11 other friends. “We were appalled at the violent images we saw on TV and wanted to take action.”

The women later got in touch with Yasser Kashlak, a 36-year-old Syrian of Palestinian origin, who heads the Free Palestine Movement. Kashlak had contributed to the financing of other vessels that tried breaking the siege, including the Gaza Freedom Flotilla and the Naji al Ali.

“After the Mavi Marmara incident, one of the women hailed Mary during our weekly meeting. Her exclamation came like a revelation, so we decided to call our ship Maryam [Mary in Arabic]. The name was perfect for a vessel that comprised only women. Who could disparage the Virgin Mary, a recognized saint in most religions?” says Hajj.

The ship is slated to make a stopover in a friendly port before heading to Gaza because of the palpable hostility between Lebanon and Israel. Last month, the Cypriot government banned any vessel headed to Gaza from its docks. But activists can still sail from a port in Turkish Cyprus.

“We have the option to sail from a number of friendly ports and are completely aware of our obligation to transit through a foreign port to avoid our trip being labeled an act of war,” says Hajj.

Hajj estimates that she has received about 500 applications for the trip, but the Maryam will transport only about fifty women, half of who are Lebanese nationals, the rest being Arabs, Europeans and from the US. The organizer explains that carrying Palestinians on the ship is not an option because of the risk of arrests by Israelis.

“The ship will transport cancer medicine and other necessary items for women and children. We will not carry any weapons or terrorists, irrespective of what the Israeli army might say,” says Hajj.

While they wait to set sail, the headquarters of the Maryam remains agog with activity as women from different backgrounds, political affiliations, nationalities and religious beliefs converse, argue and joke.

“All women traveling on the ship have taken on the name ‘Maryam’ and are distinguishable by a number, like ‘Maryam 1,’ ‘Maryam 2,’ etc. We prefer to keep identities secret to avoid pressure from respective embassies,” adds Hajj.

“Maryam 1” is a middle aged Indian lawyer and the wife of an admiral. “I am a follower of the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi who fought against every form of oppression peacefully in the course of his life. He was also opposed to the occupation of Palestine,” she says.

The lawyer explains that before deciding to join the Maryam, she studied the legal implications of the attack on the Freedom Flotilla, which she says was illegitimate.

“What the Mavi Marmara attack highlighted was that two sets of rules were applied to humanity, depending on a people’s color, race and religion. But what people fail to realize is that suffering is by nature indivisible.”

Sitting across from her was “Maryam 2,” a former biologist of Lebanese-Armenian descent. “I have been closely following the Palestinian issue and have been moved by the blatant injustice that is practiced against Palestinians by the Israelis,” she says.

At the daily meetings, “Maryam 2” bonded with other women from diverse backgrounds, particularly a Turkish journalist. Turkey and Armenia have been at odds since the Turkish massacre of Armenians in the early 20th century.

“The journalist, who barely speaks English, told me I was a godsend when she discovered I could speak some Turkish. Here at the Maryam headquarters, nationality and religion dissolve behind the common resolve of breaking the siege of Gaza,” she says.

The sail date for both aid ships from Beirut has yet to be announced. Lebanese Transport Minister Ghazi Aridi said the Naji al-Ali is now docked at the northern Lebanese port of Tripoli and can set sail once it is cleared by port authorities. However, the pan-Arab daily al-Hayat reported recently that the sail of the two ships has been postponed until further notice, particularly after Iran canceled sending two aid ships to the area. The report was denied by Saer Ghandour, the organizer of the Naji al-Ali sailing, who added that the ship’s formalities were still in process.

Meanwhile, most Maryam passengers are impatient to set sail. “We will not fight Israelis with weapons, stones or knives, but with our free will,” says “Maryam 3,” a single woman working in the Lebanese government. “And we will not surrender.”

In Israel, the army chief, Gabi Ashkenazi, told the Knesset’s Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee on 6 July that every effort should be made to ensure that no more flotillas set sail for Gaza.

“Now a Lebanese flotilla with women and parliament members is getting organized. Israel is trying to prevent its departure in open and covert ways.”

All rights reserved, IPS — Inter Press Service (2010). Total or partial publication, retransmission or sale forbidden.