The Electronic Intifada 28 June 2004

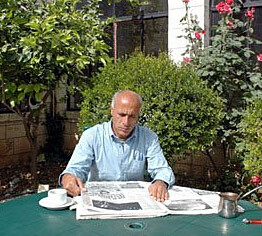

Mordechai Vanunu reads a newspaper in the grounds of the Anglican cathedral of St George’s, East Jerusalem. (Meir Vanunu)

Vanunu, who found sanctuary in the grounds of the Anglican cathedral of St George’s when he was released from jail two months ago, is under a severe gagging order imposed by the Israeli government. He is banned from talking to all foreigners and most especially foreign journalists as the former Sunday Times reporter Peter Hounam discovered a few weeks ago when he was arrested by the Shin Bet secret services, held in a cell for 24 hours and then deported. Hounam’s crime was to arrange an interview for the BBC with Vanunu, trying to get round the restrictions by using an Israeli citizen to pose the questions.

These are not the only invisible bars still imprisoning Vanunu: he is also banned from entering internet chat rooms, he must not approach any foreign embassies, and his phone calls are being continously monitored.

But the severest restriction has been the confiscation of his passport to prevent him from leaving the country — an infringement of his civil liberties he is currently challenging in the courts. Vanunu says that since his release he has been receiving a flood of death threats from Israelis, most of whom revile him as a traitor, and that he wants to leave for the safety of Europe or the United States.

Israel, however, claims that the gamut of restrictions is needed because, even after 18 years, Vanunu still has many secrets to tell that could jeopardise the country’s security. Officials argue that it was for this reason he had to endure 12 years of absolute solitary confinement, a further six years of segregation from other prisoners and now these latest restraints.

Critics, including his family, friends and supporters, on the other hand, claim Vanunu revealed to the world all the secrets he knew in 1986. In any case, they add, it is inconceivable that Israel has not overhauled the security arrangements at its nuclear weapons plant in the Negev desert in the intervening 18 years.

Vanunu’s treatment, says his brother Meir, who is living with him at St George’s, is a continuation of the psychological torture he endured in prison, a form of abuse designed to break his spirit. It has nothing to do with Israel’s security.

Meir Vanunu suggests another motive for his brother’s continuing confinement: Israel is hugely embarrassed by the timing of their whistleblower’s release. It highlights Israel’s formidable nuclear arsenal at precisely the moment when the justification for attacking Saddam Hussein’s Iraq - his possession of weapons of mass destruction - is shown to have been hollow. If Vanunu were free to talk, he might remind the world that the greatest threat to Middle East peace comes not from Baghdad but from Tel Aviv. That is a message neither America nor Britain wants to hear right now.

After my stay at St George’s there is little doubt whose story — Israel’s or Vanunu’s — is more plausible.

Despite claims that Vanunu is a walking timebomb of information that could destroy the Jewish state, he has been talking freely to hundreds of tourists and pilgrims who have passed through St George’s since he moved there two months ago. All are desperate to hear his stories.

I chose caution and avoided speaking directly to Vanunu over the breakfast table but my wife, who is an Israeli citizen and therefore permitted to talk to him, chatted as I ate. I can reveal that neither I nor my wife heard anything new about Israel’s nuclear weapons programme.

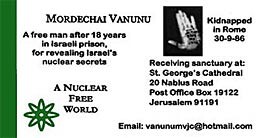

Mordechai Vanunu’s business card

All this is happening under the watch of the Shin Bet. They must be aware of what has been taking place: the guest house is only a few yards from Israeli government buildings and the American consulate.

The truth is that the Israeli authorities know full well that Vanunu can do no more damage to Israel - apart, that is, from reminding the world where the real weapons of mass destruction are to be found. The current gagging orders are a desperate attempt to prevent him from talking to journalists and to keep an embarrassing spotlight off Israel’s nuclear stockpile. And the restriction on Vanunu leaving the country is a cynical ploy to stop him inspiring a campaign in the West to disarm the only rogue nuclear state in the Middle East.

His continuing confinement — and the danger that places him in — are a stain on Israel’s honour.

Related Links

An edited version of this article first appeared in the Guardian newspaper on Friday 25 June 2004. Jonathan Cook is a journalist whose work has appeared in the Guardian, International Herald Tribune, Al-Ahram Weekly, and other newspapers. Based in Nazareth, Cook is an occasional contributor to EI. He is currently writing a book on the Palestinian citizens of Israel.