The Electronic Intifada 6 February 2004

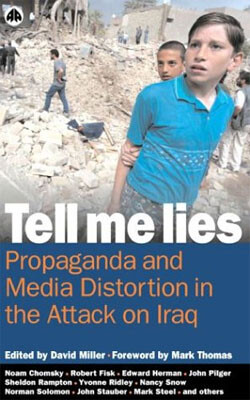

The cover of Tell me Lies. Click to purchase the book on Amazon.com

The approach of the programme - made by Arts rather than News and Current Affairs - reflected the general run of BBC domestic coverage of the issue: the strained effort at “balance”; the failure to question the circumstances of the beleaguered historical sites (why are they beleaguered?); the acceptance of the “equivalence” of the two peoples fighting over this territory, the indigenous population and an occupying army; the assumption on which the whole programme was built: that in the then looming Anglo-American invasion of Iraq these historical and holy places might be damaged by missiles fired from Iraq. Perhaps BBC Arts was not aware before their team arrived that many ancient Arab monuments had already been besieged, shelled, violated, ransacked, bulldozed, and in many cases closed to their worshippers and their inheritors by Israel’s occupying army.

A week earlier, in a BBC News documentary about the wall that Israel is building between the Israelis and the Palestinians (2) - much of it encroaching on occupied Palestinian land, destroying houses and olive groves and dividing families - it was again felt necessary to leaven the images of Arab suffering with the “balance” of how awkward the wall would be for a handful of illegal Jewish settlers. To explain this, a sympathetic Irish woman settler told that side of the story in the vivid English of her people.

It was not that the BBC did not tell the Palestinian story graphically and shockingly - but that “the other side” of the story had to be told as well, diluting the central and violent issue of The Wall and all it symbolises of Israel’s fears, greed and brutal dismissal of its Arab neighbours.

Since the beginning of the Aqsa Uprising, or Second Intifada, in September 2000 there have been countless examples throughout the BBC’s news broadcasts, discussion programmes, features, documentaries and even online of this muddying of the clear waters of the Israel-Palestine crisis. Elsewhere in this book academics and analysts such as Greg Philo give a scientific, actuarial account of this carelessness with the public broadcaster’s duty. Without the room to print my long litany of the BBC’s sins of omission and commission, I can best highlight my findings this way: Channel 4 News at 7pm is the only mainstream television news/current affairs bulletin that has tried consistently to do justice to this story, which sits at the centre of world affairs and the west’s political engagement overseas.

Where Carlton TV has shown John Pilger’s graphic Palestine is Still the Issue (3) and Channel 4 Sandra Jordan’s death-defying story of the International Solidarity Movement (4) the BBC has made no effort to tell us truly - as did these two documentaries - how this occupation demeans and degrades people: not just the killing and the destruction, but the humiliation, the attempt to crush the human spirit and remove the identity; not just the bullet in the brain and the tank through the door, but the faeces Israel’s soldiers rub on the plundered ministry walls, the trashed kindergarten; the barriers to a people’s work, prayers and hopes.

In the news reporting of the domestic BBC TV bulletins, “balance”, the BBC’s crudely applied device for avoiding trouble, means that Israel’s lethal modern army is one force, the Palestinians, with their rifles and home-made bombs, the other “force”: two sides equally strong and culpable in a difficult dispute, it is implied, that could easily be sorted out if extremists on both sides would see reason and the leaders do as instructed by Washington.

In London, respectful BBC presenters talk calmly to articulate Israeli politicians, spokesmen and apologists in suits in studios; from Palestine comes the bad-quality, broken voice on a dusty wire from some wreckage of a town. It is true that BBC teams risk their lives in the midst of the violence, but soon they are back in their Jewish Jerusalem studios, finding the balance for their pieces, so that the rolling tragedy of occupation can somehow be ameliorated by the difficulties inside Israel.

When suicide bombers attack inside Israel the shock is palpable. The BBC rarely reports the context, however. Many of these acts of killing and martyrdom are reprisals for assassinations by Israel’s death squads, soldiers and agents who risk nothing as they shoot from helicopters or send death down a telephone line. I rarely see or hear any analysis of how many times the Israelis have deliberately shattered a period of Palestinian calm with an egregious attack or murder. “Quiet” periods mean no Israelis died… it is rarely shown that during these “quiet” times Palestinians continued to be killed by the score.

In South Africa, the BBC made it clear that the platform from which it was reporting was one of abhorrence of the state crime of apartheid. No Afrikaaner was ritually rushed into a studio to explain a storming of a township. There is no such platform of the BBC’s in Israel/Palestine, where the situation is as bad - apartheid, discrimination, racism, ethnic cleansing as rife as ever it was in the Cape or the Orange Free State.

We are not reminded, continually and emphatically, that this strife comes about because of occupation. Occupation. Occupation. This should be a word never far from a reporter’s lips, stated firmly and repeatedly as the permanent backdrop to and living reason for every act of violence on either side.

Much of the explanation of events the BBC offers from the scene reminds me of the “on-the-one-side-on-the-other-side” reporting that bedevilled so many years of BBC reporting from Northern Ireland. The performance in the London studios is little better. Presenters and reporters are, on the whole, not well briefed on the Middle East. They are repeatedly bamboozled by Israel’s performers. Time and again, presented with an Israeli or some inadequately flagged American or other apologist for Israel, the presenter will accept the pro-Israel version of the truth at face value, respectful of an American accent, a well-dressed politician or an ex-diplomat (who is often nothing like as disinterested as it would appear), (5) while pressing hard on the recalcitrant Arab. (6)

The Arab view is not properly heard. This is partly an Arab problem, in that there are not enough articulate and willing Arabs readily available to go to studios or answer the telephone. But this is only part of the problem: the BBC has been plied with lists of suitable people by organisations such as the Council for the Advancement of Arab-British Understanding, the Arab League, individual embassies and private people, only for these lists to be ignored. Whether this is through inefficiency or deliberation, it is hard to say. I do know, for example, that the ambassador for the Arab League had, between January 2003 and the end of the Iraq war in early April, appeared once on BBC TV; a colleague of mine who is one of Britain’s most articulate and intelligent Palestinian spokespersons is missing almost completely from mainstream BBC television and rarely heard on domestic radio. (7)

Why is the BBC so poor at covering Israel/Palestine (for the purposes of this chapter I am concentrating on the BBC’s domestic output - BBC World Service and to some extent BBC World TV could easily be the product of a different organisation)?

In the past dozen years or so, the BBC has become a vast, impersonal, extremely successful organisation - a corporation in a very modern sense, rich, powerful, crushing the opposition, riding high and expanding in many directions. It is on the verge of being a commercial organisation, with its diversity of interests. Certainly the spirit of its Charter has been bent nearly to breaking point. It certainly behaves like a commercial company in its ruthless pursuit of ratings and the descent of its terrestrial TV channels down-market, proper current affairs programming being a significant victim of this process.

The difference between the BBC and other private concerns, however, is that in the BBC’s case its only shareholder is the British government: it prospers or fails by its licence fee, which is fixed by the government. The more generous the government is to the BBC the more unwilling is the BBC to cross that government in any significant way. Why rock a comfortable boat? It is also true that the more one owns the more one loathes to lose it. This was not true of the BBC of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. Since the advent as director general of John Birt, (8) the Blair government has smiled on the BBC. We thus have what might be termed a Blairite tendency at the BBC, an unwillingness to cross New Labour on matters close to its heart; and the Middle East has been at the very centre - outside Europe - of Tony Blair’s foreign policy concern.

The Blair vision of the Middle East - that the Americans have all the answers, but need a little gentle coaxing from Whitehall, that the Israelis are victims of terror, and “terror” is our main universal enemy, that the Palestinians are their own worst enemies and must do what they are told - will have been sensed at the BBC and passed on down the line.

It is no secret that Blair is very close to Israel. His old crony and party financier, Lord Levy, has been rewarded with the post of special adviser on Middle East matters. Lord Levy is a peer who has close contacts with Israel and a multi-million pound villa near Tel Aviv - his son Daniel Levy worked in the office of Israel’s former Justice Minister, Yossi Beilin. The first stress in any New Labour comment on the Palestine-Israel crisis is always on Israeli security or on “terror”, that easy bete noir of the modern politician (the BBC has uncritically accepted “The War on Terror” as a phrase with meaning).

Thus there is much for the BBC to be aware of as it peers out over the carnage in the Occupied Territories. The process of getting the boys in the front-line into line does not work by diktat from above but by hint and nudge and whispered word, almost, in such a very +English+ way, by extra-sensory perception - rather as until the mid-1960s a Tory Party leader would +emerge+ rather than be chosen.

Eager to help in this insidious process, squatting there in the gardens of Kensington, is the Israeli embassy, emanating influence and full of tricks, with many powerful friends and supporters. The first bloody month of the Second Intifada took the Israelis by storm. Their responses were crude and ill-thought-out. They received a highly critical international press after Ariel Sharon stormed on to the Haram al-Sharif, the Palestinians erupted and the Israelis started their killing spree. The Israeli machine recovered quickly, and immediately turned its attention to the BBC. One experienced reporter in the field told me how producers from The Today Programme would ring the office in Jerusalem with story ideas launched by the Israeli embassy; how the Israeli version of events was so often received as the prevailing wisdom in London; how Israel successfully amended the very language of reporting the crisis.

For a short while on BBC news, “occupied” territories became “disputed”. We heard much of Palestinian “claims” of occupation rather than of the 33-year-long fact of it. Illegal Jewish settlements near Jerusalem became “neighbourhoods”. Palestinians +are+ killed (it happens); but +Palestinians kill+ Israelis (that is deliberate); dead Israelis have a name and identity, dead Arabs are - just, well, dead Arabs. When Palestinians die their bereaved vent “rage” at apparently riotous funerals; Israeli survivors express shock. The list goes on. The news-speak of the crisis was adjusted to favour the Israeli side. (9)

Then, unfortunately, the BBC’s experienced team in Jerusalem was removed at the beginning of this new upheaval in Israeli-Palestinian affairs - not through any Zionist-inspired plot but because correspondents’ and producers’ contracts or tours of duty were expiring. I do not wish to malign the new reporters’ professional expertise, as reporters, but it was a bad moment for an across-the-board reshuffle. The BBC should have staggered the changeovers and deployed people more experienced in Middle East or even in similar crises - the Balkans, for example.

London and its attendant Israeli pressure teams were thus writing on blank sheets for a while. The worst excesses of that early period have ended and the use of language is more accurate - though phrases like “ceasefire”, implying the existence of two armies, and “terrorist”, too often used as a synonym for “resistance”, underscore the already false projection of the conflict. Through it all, the policies of artificially striving for balance and equivalence remain, and the people on the ground have neither the skills nor strength to resist this policy or circumvent it with subtlety. To be fair to them, perhaps they would quickly be removed if they tried.

The matter is further complicated by the cornucopia of BBC news outlets that now exists. This phenomenon harms news coverage in many ways. As the head of BBC Newsgathering, Adrian Van Klaveren, told a media conference in London in February: “We [the viewers and listeners] are victims of the broadcasting culture where there is so much broadcasting that none of us, even an interested audience can hear any more than a fraction of what [the BBC] do.” (10) This cuts many ways. Mainly, it means that the BBC can banish the awkward squads who might raise (or

answer) real questions about the Middle East to the watches that end the night. Critics who say the Palestinian or Arab view has not been aired can be referred to the World Service at 3.00am, or News 24 at 6.00am, and so on.

Anyone who listens to The World Tonight, on Radio 4 at 10.00pm, will know that the level of programming and presenting is far more searching and alert to the twists and nuances of foreign affairs than Today. A few hundred thousand may listen to radio at 10.00pm (in competition with the BBC’s main TV news and its oversimplifications and star “brand” reporters), while millions tune in to Today, which throws its heaviest weight into domestic matters and is inconsistent and often badly briefed on foreign affairs, particularly those in the Israeli-occupied Territories. (11)

The profile of the listening and viewing world is changing. Many people, especially the young, now listen to and watch all kinds of channels at all times of night and day. Stations like BBC Asia Network and Radio Five Live are boisterous and irreverent, with well-informed callers, many of them from Muslim, Arab, Asian and other ethnic groups. Britain’s political leaders and Israel’s supporters, however, do not apply themselves to these people’s forums. What they care about are the mainstream outlets, Today, The World at One, PM, Breakfast News, the one o’clock, six o’clock and ten o’clock television bulletins. The BBC, alert to this, shapes the tone of its correspondents’ and reporters’ coverage, and its presenters’ and producers’ attitudes accordingly: very cautiously, in lockstep as close as can be with the government and the policy-makers at No.10 Downing Street.

In fact, the coverage of the Blair government and its personalities is often more critical than coverage of Israel.

One reason for this may be the phrase that terrifies the managers of the Corporation, though it is widely misused, abused and manipulated: this is anti-Semitism. Anything critical of Israel is liable to raise that spurious charge; spurious or not, BBC bosses do not want to hear it let alone try to answer it or argue against it intelligently. At a recent writers’ festival in Sydney, the Palestinian author Ghada Karmi, who has good reason to know about this phenomenon - Woman’s Hour apparently refused to consider her book In Search of Fatima: A Palestinian Story for serialisation or author-interview unless an item of “Jewish balance” could be found - strongly criticised the BBC’s nervousness about anti-Semitism, which, she told a large and appreciative Australian and international audience of writers and journalists, was seriously undermining the BBC’s fairness in dealing with the complexities of the Middle East.

The novelist and broadcaster Sarah Dunant publicly confirmed this view to the conference, saying that all European journalists were constrained in their reporting by this consciousness of avoiding anti-Semitism. (12)

For example, lurid Israeli stories of anti-Semitism in the Arab press are taken at face value, while similar abuse of Arabs by Israelis is rarely reported. Both phenomena exist but only one is belaboured.

As I write this chapter, in mid-June 2003, the BBC has consigned a profile of the Palestinian intellectual, author and activist Edward Said, a giant mind of his time by any measure, to a late-night showing on BBC4, a minority channel. (13) It was not advertised; its time was changed from 8.30pm (a prime slot right after the BBC4 news bulletin) to 10.00pm at the last minute, again without publicity. Much of this kind of programming is shunted to the late hours or minority channels.

The only decent documentary the BBC has made about Israel, a searching examination of the Vanunu affair, was also postponed a day, from a prime time, and dismissed to a late-night showing. (14) (To be fair to the BBC, Carlton also put John Pilger’s Palestine programme out late at night. After it was shown, the chairman, Michael Green, excoriated the programme, saying it should never have gone out. (15) Many other friends of Israel joined Green in complaining to the ITC about bias, but the Commission resoundingly endorsed and vindicated the programme. (16) At least the chairman of the BBC Board of Governors does not publicly revile his organisation’s programmes hours after they have been transmitted.)

There are less easily avoidable reasons for the BBC’s mishandling of the Palestine-Israel issue. Much of the seeming bias in the coverage - and not just at the BBC - is endemically and accidentally cultural. To a westerner sitting at a screen in London a dead or suffering Arab in the rubble of a bazaar is more remote than a dead or suffering Israeli in a shopping mall with a Wal-Mart in-shot; studios favour good English-speakers rather than men with heavy accents; producers like quality sound and vision. It is a presenter’s inclination, in many cases, to take more seriously a representative of a state and an authority, a uniform or a dark suit, than a denizen of what is, after all, not quite a state but still a national revolutionary and resistance movement, a man perhaps in a keffiyeh or a militia uniform, speaking poor English or being translated or subtitled.

All this is true, but it is no excuse. The BBC has to work hard to counter this cultural drift. It has to strive for proper balance between the state and the stateless. Conscious effort and caution has to be applied at all times, and it is not easy in busy, overworked, high-turnover newsrooms.

The BBC has to be courageous. It has to do more to understand and have presented properly the Arab-Palestinian case. It has to find those many Palestinians and Arabs, and their interlocutors and experts on the region, here and in the Middle East, who can put and explain the Palestinian case. It is, after all, not so different from the plight of the Africans, Indians, Coloureds and liberal-minded Whites who struggled for so long in South Africa, and about whom the BBC reported with fairness and integrity.

The news chiefs should move more people out of West Jerusalem. It should base a news team in the West Bank - not just some luckless stringer but a senior, known correspondent who can force his or her way onto the main bulletins (what the BBC likes to call a “brand” reporter). Here the reporters will feel what daily life under occupation is like, live it and empathise with the people crushed under it, as news crews lived the invasion of Baghdad or as we experienced the Israeli invasions and occupation of Lebanon - from the inside, not just down there on a visit.

It seems, however, that the policy-makers at the BBC are not as brave as the reporters, producers and cameramen they send into the field. It is more troubling for a boss to field an angry phone call from the Board of Deputies of British Jews or receive an abusive letter from Golders Green or to read a bilious article in the Daily Telegraph than it is for a camera crew and correspondent to venture down the road to Nablus, past those trigger-happy roadblocks and into those dangerous alleyways, and still find their cut story watered down with the countervailing view from a balcony in West Jerusalem.

Despite all this, the sheer imagery of the crisis - tank against stone, soldier against civilian - is making its weight felt. The British public are becoming more and more uneasily aware that the words do not quite match the pictures. The euphoria that greets each new peace plan - the “road map” is the latest - and is picked up so eagerly by a flag-waving, cheer-leading broadcast media no longer takes with it, I think, the average viewer.

The Corporation’s timidity about telling the truth from Palestine is not about informing the viewer, however, but about keeping protectively in step with government and projecting its future into the twenty-first century.

Endnotes

1. The Road to Armageddon, BBC2, 8pm, 7 June 2003.

2. “Behind the Fence”, Correspondent, BBC2, 7.15pm, 25 May 2003.

3. Palestine is Still the Issue, Carlton TV, 11.00pm, 16 September 2002.

4. “The Killing Zone”, Dispatches, Channel 4, 8pm, 19 May 2003.

5. Two good examples of misrepresentation are those of Martin Indyk and, more especially Dennis Ross, both former US diplomats whom the BBC regularly trundles out to pontificate from apparently Olympian, though expert, detached heights about the Israel-Palestine crisis. It is never pointed out that both men are Zionists and former members of the powerful American Jewish lobby organisation, AIPAC.

6. One outstanding example of this was the Newsnight of 30 November 2001, BBC2, when Jeremy Paxman gave the former Israel Prime Minister, Binyamin Netanyahu, an astonishingly easy ride then bullied the British Palestinian barrister - Michel Massih - an inexperienced TV broadcaster - with repeated rapid-fire accusations about suicide bombs and terrorism. The BBC bosses reprimanded Paxman. Paxman is not alone in this tendency to let Israelis get away with it but treat Arabs as if they are prisoners at the bar.

7. If three London Palestinians - Dr Ghada Karmi, Afif Safieh, the Palestinian ambassador-equivalent in London, and Abdel Bari Atwan, editor of the Arabic language daily Al Quds Al Arabi - were to fall under buses tomorrow, the Palestinian case would almost cease to exist as far as the BBC is concerned. It has to be said that they are all used far more sparingly than the importance of crisis demands.

8. When John Birt came into the BBC in the late 1980s, first as deputy Director-General than as full DG, his main task was to bring into line a BBC the Thatcher government saw as a rival centre of power. He did his job well. His successor, Greg Dyke, while not bucking government has developed the commercial nature of the Corporation.

9. Martin Woollacott, the eminent Guardian foreign affairs columnist, described this well at a media conference in Dubai in April 2002, saying “the Israelis have captured the language”.

10. “Reporting the World”, a media conference at the Guardian/Observer building on 20 February 2003.

11. One excepts from this Today ‘s brilliant post-Iraq War coverage — but this is essentially a domestic political story.

12. Sarah Dunant is a regular presenter of BBC Radio 3’s Night Waves and has broadcast intelligently on, inter alia, Palestinian cultural affairs. It must also be pointed out that no decent journalist would have any dealings with real anti-Semitism — it is the false, blanket charge of anti-Semitism and the obsessive fear of incurring it that actually devalues the currency of language and paradoxically assists real anti-Semitism.

13. A Profile of Edward Said , by Charles Glass, BBC4, 10pm, 9 June 2003.

14. “Israeli Nuclear Power Exposed”, by Olenka Frenkiel, Correspondent , BBC2, 11.20pm, 17 March 2003.

15. ITC ruling handed down on 17 January 2003.

Tim Llewellyn is a former BBC Middle East correspondent, based in Beirut from 1976-1980 and in Cyprus from 1987-1992. He is now a freelance writer and broadcaster on Middle East affairs, living in London, and an executive board member of the Council for the Advancement of Arab-British Understanding (CAABU) and of the Arab British Centre, in London. This article was first published in the book “Tell me lies: Propaganda and Media Distortion in the Attack on Iraq”, edited by David Miller, Pluto Press,