The Electronic Intifada 23 May 2018

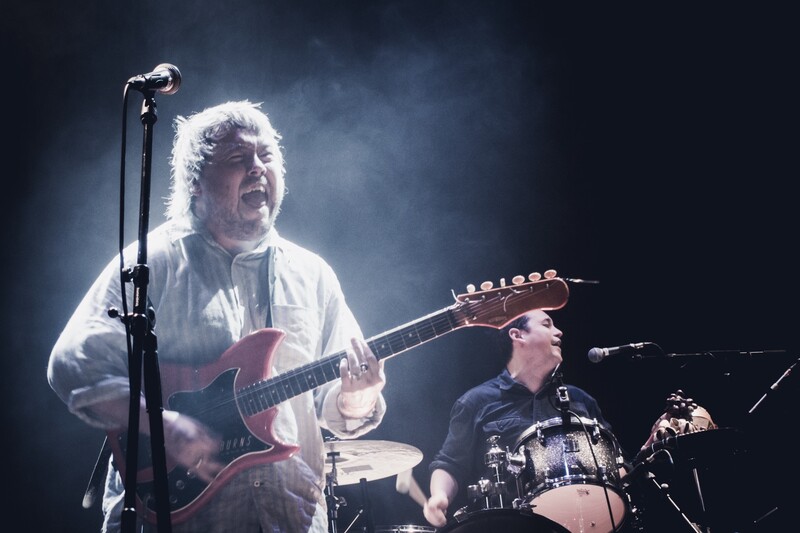

Richard Dawson is among a group of artists who have pulled out of Pop-Kultur Festival 2018. (Paul Hudson)

The Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI) has launched a campaign to boycott Berlin’s Pop-Kultur Festival in mid-August in protest at the Israeli embassy’s sponsorship of the international event.

“Israel seeks associations with international festivals, such as Pop-Kultur Berlin, to art-wash its image abroad in the explicit attempt to distract attention from its crimes against Palestinians,” PACBI explained in its press release.

“For a supposedly progressive festival to accept sponsorship from a decades-old regime of oppression and apartheid like Israel’s is unethical and hypocritical, to say the least.”

In response, festival organizers said they would not be “intimidated” and published a statement disclosing the extent of its cooperation with the Israeli embassy.

“We will collaborate with the Israeli embassy this year because our 2018 lineup includes three Israeli artists,” the organizers stated. “We will receive a total travel and accommodation contribution of €1,200 [approximately $1,400] from the embassy.”

The campaign was launched on 9 May and has already garnered support from Palestine solidarity groups in the German capital and abroad.

Jewish Antifa Berlin and Jewish Voice for Just Peace in the Middle East were quick to publish a joint message of solidarity, while legendary musician Brian Eno gave an interview to organizers, voicing his support for the boycott, divestment and sanctions (BDS) campaign in general.

Berlin Against Pinkwashing, a queer international group, released a statement in support of the campaign while UK artists Shopping, Richard Dawson and Gwenno Saunders have all withdrawn from the festival in solidarity with the Palestinian call.

“It’s not about the money”

Last year, BDS Berlin also called to boycott Pop-Kultur when the festival accepted a small donation from the Israeli embassy to go toward artists’ travel expenses in return for displaying the embassy’s logo on the festival website.

Some criticized the response as disproportionate to the approximately $590 the embassy had given but supporters of the boycott said the size of the donation was immaterial.

“It’s not about the money, it’s about the publicity they [the embassy] received,” Bahia Mahra, a local Palestinian activist, told The Electronic Intifada.

That campaign, called last-minute owing to the late announcement of the Israeli embassy’s involvement, was more spontaneous in character than this year’s effort. The call only came after Syrian rap artist Mohammad Abu Hajar and other Arab artists announced their intention to withdraw. Eight acts in total withdrew.

Festival organizers released a statement claiming BDS had “put intense pressure on all Arabic [sic] artists in our lineup,” a point repeated across local and national German media outlets, while failing to note that the four Arab artists who canceled did so before the campaign launched. News coverage followed a similar line, painting the campaign as an essentially “Arab” boycott.

The Pop-Kultur statement also characterized BDS as an attempt to “boycott completely any cooperation with Israeli artists and intellectuals or performances in Israel.”

Ronnie Barkan, a Jewish Israeli activist and BDS Berlin member, refutes the claim.

“We don’t boycott individuals, we boycott institutions. We will not boycott Israeli artists simply because they are from Israel, but we will boycott those who choose to act as cultural ambassadors for an apartheid state,” he told The Electronic Intifada.

“We will not normalize what is not normal or legitimize what is not legitimate.”

Watershed moment

Activists consider last year’s campaign a watershed moment in Germany.

“Until the boycott of Pop-Kultur festival in 2017, most people, including the media in Germany, didn’t even realize BDS was a global movement,” Doris Ghannam, a BDS Berlin member, told The Electronic Intifada.

“It’s had the result of opening up sorely needed spaces for debate about the nature of white supremacy and racism in Germany, as well as regarding reflexive support for Israeli apartheid.”

Historically, the environment has been hostile in Germany. Individuals and organizations expressing support for the Palestinian struggle have often been the target of verbal and physical violence.

Last year, Barkan and two other activists protested an event at Berlin’s Humboldt University where Aliza Lavie, a member of the Israeli parliament, was scheduled to speak. The demonstrators disrupted the session, highlighting Lavie’s role in the 2014 attacks on Gaza. During the protest an event organizer allegedly punched the female member of the group.

When protesting Israeli pinkwashing policies at the capital’s main pride event in 2016, Berlin Against Pinkwashing was met by a violent crowd, among them German politicians Oliver Höfinghoff and the center-left’s Andrew Walde, chanting “long live Israel.”

Berlin Against Pinkwashing held a similar demonstration the following year, where a lone counter-protester was seen attempting to pull down the group’s banner.

Artists and politicians have also been targeted. Spoken word artist Kate Tempest canceled a concert scheduled to take place at the former Berlin airport Tempelhof last October due to personal threats received via mail and social media.

The poet, who is of Jewish background, had signed an “Artists for Palestine” pledge in 2015 expressing support for the Palestinian struggle and a commitment to the cultural boycott of Israel.

One German newspaper published an article entitled “Can an anti-Israel activist appear in Berlin?” while another called on Berlin Mayor Michael Müller to cancel the concert.

In the weeks following the Pop-Kultur boycott campaign, it was reported that the Simon Wiesenthal Center was considering Müller as a candidate for its annual top ten anti-Semitic/anti-Israel incidents list.

Müller had, according to some, failed to publicly distance himself from the BDS campaign. In less than two weeks, the mayor gave an interview condemning the movement as anti-Semitic and stating that he was considering a “legally binding ban” of the campaign in public spaces.

“It’s a struggle to talk about Palestine in Berlin,” said Mahra. “As a victim of colonization and ethnic cleansing, you want to talk about the history, but every time you talk, it’s as if you are responsible.”

She added, “I have found that, in public, Germans want to prove to the world that they have learned from the mistakes of their forefathers and changed, but to do this they ignore the suffering and oppression of Palestinians.”

Palestine solidarity in Berlin

Despite the level of hostility, there exists in Berlin a core network of committed individuals.

“Our position on this isn’t wavering and isn’t backing down to the increasingly more pro-Israeli leanings of the German media,” said a member of Jewish Antifa Berlin, who asked not to be named. “We have our position and it is with the Palestinian people.”

The group contends that the quality and the diversity of acts on show at the Pop-Kultur Festival make it “the perfect stage” to advance a message of normalization. “As people who live in Berlin and as Jews, in whose name the Israeli state claims to act, we should not let that happen or let that go without a say.”

Ghannam spoke most clearly to the urgency of the situation: “During times like these, when Israel attacks and kills – without accountability – Palestinians who are peacefully demanding their rights under international law, it is essential to support Palestinians through boycotts, in Germany as well.”

“Responsibility for German history, of which many in this country talk, implies freedom, equality and justice for all, including Palestinians. The time for being deeply concerned is over. The time to act is now.”

This article has been corrected to state that eight performers withdrew from Pop-Kultur in 2017, not nine as originally stated.

Riri Hylton is a freelance journalist/editor working in both print and broadcast journalism. They are based between London and Berlin.

Tags

- Pop-Kultur festival

- BDS

- PACBI

- Jewish Antifa Berlin

- cultural boycott

- Jewish Voice for Just Peace in the Middle East

- Brian Eno

- Berlin Against Pinkwashing

- Shopping

- Gwenno Saunders

- Richard Dawson

- Bahia Mahra

- Mohammad Abu Hajar

- Ronnie Barkan

- Doris Ghannam

- Germany

- Aliza Lavie

- Humboldt University

- Kate Tempest

- Michael Müller