The Electronic Intifada Gaza Strip 14 March 2016

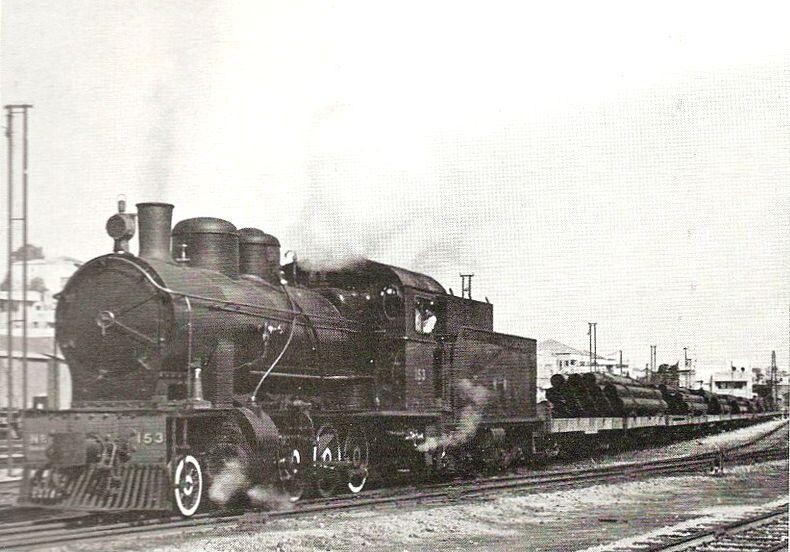

A steam locomotive operated by Palestine Railways, photographed in the Marj Ibn Amer plain in southern Galilee in 1946.

Abdelmajeed al-Mubayed still remembers when the train used to pass by his house.

The 80-year-old, whom everyone knows as Haj Abu Muhammad, likes to entertain his grandsons with tales of running after the Cairo-bound train as it billowed smoke. Picking up a head of steam for the long journey ahead, the train made its way through his neighborhood of Shujaiya in Gaza City.

“I can still hear the sound of the train,” he told The Electronic Intifada. “I remember the room where they used to sell tickets and deliver parcels.”

Those days are long gone. But there have been a number of suggestions in recent years that a Palestinian railroad should be brought back. In December 2015, the Palestinian Authority’s transport ministry announced plans to link the West Bank and Gaza by a rail network, which could then be extended to neighboring countries.

Much of this would demand a political settlement with Israel as well as agreement with a country like Egypt. In the current climate, such breakthroughs appear to be a long way off.

Nevertheless, the news set tongues wagging and memories stirring.

Forged in war

Hamid Ahmad remembers frequent journeys on the train. A dentist, Ahmad, 75, studied and received his qualifications in Cairo between 1959 and 1965. In those days, Ahmad said, the journey was easy and pleasant.

“Travel was a joy. Before we entered Egypt, we would have our papers checked, but the procedures were simple. Egypt used to welcome us at any time,” he said.

It is a stark contrast to the situation today when Gaza is cut off from the rest of the world, and Palestinians face draconian measures to pass through — on the very few occasions they are allowed to even try — either the Erez checkpoint into present-day Israel or the Rafah crossing into Egypt.

It is not hard to see why those who remember it, remember the railroad as a golden time in Gaza.

But it is sometimes overlooked that Palestine’s rail network was forged in war.

During the First World War, gaining control of the railways was a key objective for the rival powers. One method used by the British to gain control of Palestine was to build their own railways and destroy those of the Ottoman Empire.

Following the war, Palestine became well served for both domestic and international travel.

The rail connections that Palestinians used to enjoy started to deteriorate when the State of Israel was founded in 1948. Traveling between Egypt and Gaza has become increasingly difficult because of restrictions on movement imposed since 1967. The territories invaded and occupied by Israel that year included Gaza and the neighboring Egyptian Sinai.

Distant dreams

Today, talk of railways and connections with neighbors has slipped down the list of priorities for the political elite. When announcing a ““lasting truce” in Gaza after Israel’s 2014 assault, Mahmoud Abbas, the Palestinian Authority leader, mentioned no plans for a rail link between the West Bank and Gaza or any similar national infrastructure projects to promote the economic rehabilitation of the battered strip of land.

And with relations between Egypt and Hamas strained and a concerted Egyptian effort to cut off Gaza from access to the outside world, thoughts of a direct train to Cairo seem like pipe dreams.

Some have kept dreaming, all the same. Among them, evidently, are Samih Tubeileh, the PA’s transport minister. His plans to link West Bank cities with railroads, and find land routes between Palestine, Egypt and Israel were widely covered.

In a phone interview with The Electronic Intifada, Tubeileh said his ministry is working on an inclusive traffic plan for Palestine in which five foreign and Palestinian companies are involved. The plan is multi-phased, according to the minister: it starts by connecting the cities and towns of the West Bank, moves on to connecting the West Bank with Gaza, before connecting to other countries.

Pressure

“We talked to the EU, especially France, about politically and financially supporting the project. We asked them for a detailed study, and to provide the required support to establish the project and assist in obtaining licenses from the Israeli side,” said Tubeileh.

Ultimately, any such project would require Israeli approval, unlikely to be given absent a broader political agreement. Still, Tubeileh said, the PA was pushing for French and EU pressure on Israel.

Al-Mubayed does not know if the trains will ever come back to Gaza. And if they did, theirs would not be the steam engine noise of his memory.

Nevertheless, what little remains of the railway can still be seen in his neighborhood. There is little doubt al-Mubayed would like the chance to once again see a train take people from Gaza to Egypt and from there the outside world, needing just their travel documents.

Reviving the “glories of the railway,” al-Mubayed said as his grandsons gathered round him at dusk, would be very significant. It should be one of the most “important demands” for Palestinians. It would make life “much easier for the people of Gaza,” he said, and ensure a “better future for our grandsons.”

Hamza Abu Eltarabesh is a journalist in Gaza.