The Electronic Intifada 4 May 2020

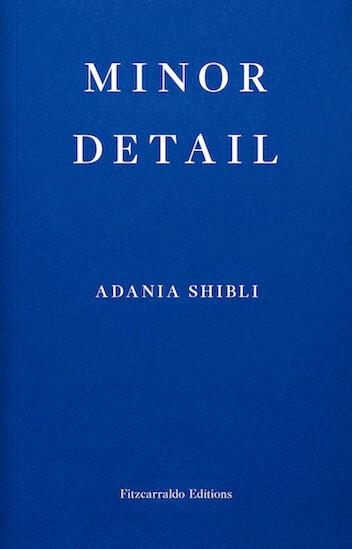

Minor Detail by Adania Shibli, translated from Arabic by Elisabeth Jaquette, Fitzcarraldo Editions (2020)

A slim volume running just over 100 pages, the physical lightness of Palestinian writer Adania Shibli’s third novel, Minor Detail, belies both its weight and its strength.

The narrative of Minor Detail has some monologues but no dialogue or named characters, although the place names and dates are recorded with military precision. It is composed of two interlinked accounts, mirroring back at each other through time.

Each line is muscular, yet agile; language is efficient, illuminating. And although the plot is lean, the compulsion to follow is strong.

Minor Detail has the qualities of a classic: original, distinctive, determined; revealing everything, while dictating nothing.

Boot in sand

The novel starts from the perspective of an Israeli soldier, a commanding officer of “one of the first and only platoons to arrive that far south since the armistice had been declared.” It begins on 9 August 1949 and the terrain, through the soldier’s eyes, is moribund:

“Nothing moved except the mirage. Vast stretches of barren hills rose in layers up to the sky, trembling silently under the heft of the mirage … The only details that could be discerned were a faint winding border which aimlessly meandered across these ridges, and the slender shadows of dry, thorny burnet and stones dotting the ground.”

The tone of this historic section is heavy, the pace slowed down to the trudge of a boot in sand. The routine is drab, repetitive; the details of the military day related with tedium and an unquestioning sense of obligatory actions slowed by the heat: “He took a towel from his kit bag, dipped it in the water he had poured into the bowl.”

A creature bites the soldier’s thigh; the heat enervates. Covered in sweat, he methodically searches for the intruder. A slight swelling appears around two dots.

Three days later, the bite wound has worsened and the soldier experiences nausea. On patrol that morning, the soldiers surprise “a band of Arabs standing motionless by the spring” who they kill, together with their camels.

Only a girl and a dog survive. The soldiers take in the girl, rape and kill her too.

That’s it for the first section. The description on the back of the book summarizes as much.

This intense focus on a single incident of a far larger military endeavor – the minor detail – enables the reader to engage move-by-move with the choices exercised by soldiers carrying out war crimes. Shibli demonstrates the way in which a sense of military duty obliterates, or at least suspends, independent morality.

In this case, it even blights the soldier’s ability to care for his festering, potentially life-threatening wound.

Reclaimed terrain

There are several motifs that recur in the novel as nature reclaims the terrain, infiltrating into the life-defying military encampment, in the form of arachnids, bugs, trees, heat. Dogs like the one left to survive after the oasis shooting bark in the distance across timespans.

Seven decades later, a woman, possibly not much older than the girl shot in 1949, speaks in the first person:

“After I finished hanging the curtains over the windows, I lay down on the bed. At that moment, a dog on the opposite hill began to howl incessantly. It was past midnight, and I couldn’t sleep, despite how thoroughly exhausted I was. I had spent the whole day arranging and cleaning the house.”

The jump in narratorial voices from the first to the second section of the novel jolts the reader. Unlike the soldier’s dutiful tread, this is a Palestinian, presumably living in a West Bank city, speaking directly in first-person.

She not only possesses high standards of cleanliness, but a sense of caprice, rebellion and self-doubt:

“There are some people who navigate borders masterfully, who never trespass, but these people are few and I’m not one of them. As soon as I see a border, I either race towards it and leap over, or cross it stealthily, with a step. Neither of these behaviors are conscious, or rooted in a premeditated desire to resist borders; in fact, it’s sheer stupidity. To be honest, once I cross a border, I fall into a deep pit of anxiety.”

On her way to work at her new job, a soldier points a gun at her. She stubbornly evades him to reach her office, where she reads the story of the 1949 incident in an Israeli newspaper:

“To a certain extent, the only unusual thing about this killing, which came as the final act of a gang rape, was that it happened on a morning that would coincide, exactly 25 years later, with the morning I was born. That is it. That is it.”

She sets out to investigate. What follows takes place over fewer than two days.

With sharp pen yet a restrained directive force, Shibli etches out the bludgeoning Palestinians have taken throughout Israel’s existence: the bombings, killings, home demolitions, watchtowers, checkpoints, insufferable economic circumstances and exploitation, the crushing and confusing multiple permit system, the roads that vanish, are cut, walled over or renamed, the maps that compete and contradict each other.

Juxtaposed against this is the calm politeness of the staff at the Yafa Military Museum where the air conditioning is turned up high. The narrator has traveled there to visit the museum to get more information about the 1949 incident.

She also goes to an archive in the Negev, where an Australian-born Israeli archivist rambles on near the encampment where the girl and her family met their fate in 1949.

Impasse follows impasse in accessing a Palestinian history in this terrain. At one point, the archivist stops enthusiastically regurgitating information that is reproduced on the institution’s website:

“At the end of his speech, he passes me a photograph of the lone wall standing amid the rubble, on which hung a white banner, with a phrase in Hebrew that he translates for me: ‘Man, not the tank, shall prevail.’”

The irony, if not the hope, enshrined in this slogan is not missed by this extraordinary writer.

We can but hope for the day when this exquisite, piercing novella, endorsed by the Nobel Prize-winning South African author JM Coetzee, is read on curricula concerning Palestine globally, as Coetzee’s works are following the fall of apartheid in South Africa.

Selma Dabbagh is a British-Palestinian writer of fiction.