The Daily Star 17 September 2003

“This is my father when he was on pilgrimage … This is my mother before she had a stroke … This is my sister who was pregnant when she was killed,” he said Monday, on the anniversary of the massacre. Mohammed was only 5 when the massacre took place. Twenty-one years on, he says he is unable to overcome the loss of his loved ones.

“We did not have one good day since the massacre,” says Mohammed. His family had to spend several months in an underground shelter because they had no money. “My father was a construction contractor … when he was alive, we were well-off.”

His mother had a stroke in 1990 a day after she watched a documentary on the massacres. She died several years later. “I will not forget the massacre until I go to my grave,” says Mohammed. The last time he saw his father, Shawkat, was when he was lined up with some nine other men at a wall in Shatila. He remembers how his father had to raise his hands, placing them on the wall shoulder-width apart. As the little child walked hurriedly away through the narrow alleyways of the wretched Shatila camp with his mother and sister, they heard a loud burst of bullets.

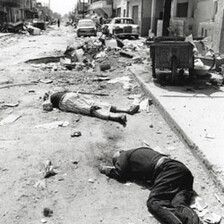

“I kept saying to myself, ‘Daddy must have escaped and he will come back to us.’” After several days, however, Mohammed knew that he would never see his father again. Relatives found Shawkat’s swollen body piled among others, all victims of one of the most heinous crimes in recent history.

Also killed were Mohammed’s pregnant sister, Amal Abu Rodaina, and her husband who lived some 300 meters away from her parents’ home. Her body was found split open with her fetus lying on her chest. “Her Lebanese neighbor who survived told us that the militiamen were betting over the sex of the baby before killing her and removing the fetus,” Mohammed says.

The massacres began three months after Israel invaded Lebanon in 1982 and two days after Lebanese President Bashir Gemayel was assassinated. On Sept. 15, Israeli tanks and soldiers surrounded Sabra and Shatila, setting up checkpoints at strategic locations and crossroads around the camps to monitor the entry and exit of every person.

During the late afternoon and evening the camps were shelled. Israeli forces used flares at night to illuminate the area. “I sat on my father’s lap and he held me like this throughout the shelling,” said Mohammed. On Sept. 16, around 150 Israeli-allied Phalange fighters, who supported Gemayel, entered the camps and the carnage began. Mohammed’s family had already moved to their uncle’s house, which they thought was safer since their home was located on the main street.

“My father was telling us not to be scared and that we would be fine. But there were gun shots and noises and we couldn’t help but cry, especially when the militiamen broke the windows of the house with their rifle butts.” Mohammed recalls how his father was optimistic that nothing bad would happen, until the armed men appeared at the door step.

“He knew that he was going to die,” Mohammed recalls. The Phalangists ordered the men to line up next to a wall just outside the house while the women and children were allowed to leave. That was when Mohammed had a final glimpse of his father.

On Tuesday, hundreds of Palestinians joined by Italian activists marked the anniversary of the massacres. They gathered at the scene of a mass grave at the entrance to Shatila. The procession then marched to the camp’s cemetery. The families of Sabra and Shatila victims had until recently been taking advantage of a Belgian anti-atrocity law to file a suit against Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, who was then Israel’s defense minister.

But a recent Belgian decision to amend the law has limited its scope to Belgian citizens, when previously it had universal jurisdiction. “The Belgians should have stood by us because we are weak … but weak people have no rights,” said Mohammed. “Justice is absent.”

With AFP