Young settlers walk down Shuhada street, banging on Palestinian families’ doors and spitting at Palestinian and international passers-by. (Dawud/ISM Hebron)

No matter how bad things get in the north West Bank, it’s never as bad as in Hebron. I’m back in the ancient city exactly two years after my last visit, to participate in several solidarity actions, among them school patrol in Tel Rumeida. This small Palestinian neighborhood of Hebron is home to some of the most violent ideological settlers in the West Bank, who have moved into local homes by force and parade the streets with guns, terrorizing local residents including children on their way to and from school. Unlike most settlers in the West Bank who move to the Occupied Territories because the Israeli government encourages them to do so with financial subsidies and other programs, the settlers in Hebron are here because they believe the city of 150,000 plus Palestinians belongs exclusively to the Jewish people.

Hebron’s were the first settlements in the West Bank after Israel occupied the area in 1967, when the Old City’s Palestinian population was around 7,500. Twenty-five years later, the population had shrunk by 80 percent to 1,500, a mass exodus provoked by Israeli settler and state violence and dispossession. The wealth left with the refugees; only the poorest residents remain, those with nowhere else to go. Their children dodge sticks and stones -— from settler children (and their parents) -— on their way to school every day as soldiers watch on indifferently; I and several other internationals accompanied the students to document and even shield the settler kids’ attacks.

A sign warning against “unauthorized” vehicles in front of Shuhada Street. In Tel Rumeida only Israeli settlers and soldiers are allowed to drive while cars belonging to Palestinians are not even allowed in. (Anna Baltzer)

Today my station was on Shuhada St, which used to be a major Palestinian thoroughfare before settlers moved in down the road and blocked it to non-Jews. Cars drive frequently through the neighborhood but they are all yellow-plated (Israeli) or jeeps; Palestinians are not allowed to use cars in Tel Rumeida. They are banned from even walking on the main street, so they wind through a cemetery to get from their neighborhood to the city. More than 2,000 small businesses in the Old City and Tel Rumeida area have closed down, and the once thriving cultural and economic center is now a ghost town.

A young Palestinian on his way to school walks past a star of David spray-painted on a Palestinian home. (Anna Baltzer)

An Israeli friend Cesca showed a colleague and me around the olive groves between Tel Rumeida settlement and the school, where a few Palestinian families are still struggling to survive. Cesca introduced us to a shepherd named Abu Thalal, who welcomed us warmly into his home. He said he’s grateful for Israeli allies like Cesca, and has even tried reaching out to the settlers who trespass on his land everyday. Abu Thelal said when a settler once asked him for a cigarette he didn’t hesitate to hand one over, and even prepared tea for the two of them. Shortly after, Abu Thelal was shocked to see the same man and his children throwing stones at his home. He shrugged after he finished the story: “There are good Israelis and bad Israelis, just like there are good Palestinians and bad Palestinians.”

From Abu Thelal’s home you can see the mosque and temple where Abraham was buried. The groves and ruins surrounding Abu Thelal’s home are not just old; they look and feel biblical. Cesca said she once watched in horror as settlers set fire to one of the hills during the Jewish holiday Lag Ba’Omer. She said they burned Palestinian flags along with the ancient land.

Jewish holidays frequently translate into Palestinian suffering in the West Bank. This past week was Purim, so closure was imposed on the entire West Bank Palestinian population so that soldiers could go home to celebrate with their families. Extra help was needed patrolling today because it’s Shabbat, when attacks are more frequent because settler children don’t have school. Last week one settler child ran down the street flailing his arms and throwing stones at Palestinians in every direction. Soldiers prevented internationals from photographing saying, “It’s ok, it’s Purim. He’s just drunk.”

Soldiers also didn’t intervene when settlers rioted in Hebron during Sukkot holiday a few years ago. According to the Alternative Information Center (AIC), “during a big march of settlers, participants started attacking Palestinian homes close to the Tel Rumeida settlement. The house of Palestinian Hana’a Abu Haykal was stoned and windows were smashed in three apartments, and settlers also injured Jameel Abu Haykal, aged 12, in his shoulder. Hana’a said the assault happened during the daytime as soldiers stood by without trying to stop the assaults, while the Palestinians were confined to the house because of curfew.”

I met the Abu Haykal family, who live literally next door to a military outpost on one side, and Tel Rumeida settlement on the other. Their windows are caged, much of their land has been declared a “closed military zone” (although settlers frequently trespass it without consequence), and they removed the staircase to the roof so that soldiers would stop coming to use it for surveillance. Settlers have done everything they can to scare away the family so they can move into the large well-situated house, but the family just won’t give up.

A mural in the Abu Haykal home. (Anna Baltzer)

The Abu Haykals have lived in their home since the neighborhood was Jewish, before Zionism and the Hebron Massacre of 1929. Settlers claim they are reclaiming Jewish territory, yet the families who left have issued joint statements demanding that the settlers leave and stop all violence against their former neighbors.

Many Jewish Israelis like Cesca have spoken out against settler violence in Hebron. Many of them came with us today on a joint action to rebuild destroyed houses in the South Hebron hills. Across the South West Bank there are dozens of tiny villages where Palestinians live in caves, tents, and small stone houses surrounded by rolling hills where they graze their sheep every day. Many years ago, fundamentalist Jews began settling hilltops all over the area, and frequently harass or even physically attack the shepherds on their land and in their villages. Settlers from the illegal outposts have poisoned village water sources with dead chickens and dirty diapers, and cemented over cave entrances. They run down the hills into villages wearing masks and carrying baseball bats or large guns. (There’s a telling image from Purim two years ago.)

To add insult to injury, the Israeli Army has been demolishing Palestinian structures across the region, most of them homes and bathroom facilities. The pretext is that the shepherds didn’t secure building permits from Israel before building the rooms and outhouses on their own land. Building permits are expensive (up to $20,000), and generally refused to Palestinians. In contrast, they are readily available to Jews who want to build homes, even on land that does not belong to them. The caravans of violent settlers who have snuck onto Hebron hilltops, surrounding the rural families, are meanwhile encouraged to flourish with subsidies, infrastructure, and protection from the Israeli state, even though they are illegal according to international and Israeli law.

Hundreds of rural Palestinians’ homes and caves have been bulldozed, and many families have fled in an exodus that can only be described as ethnic cleansing. Still, several villages remain, despite tremendous obstacles, refusing to leave their ancestral land. One such village is Qawawis, where I spent the day rebuilding homes that the army recently demolished. Organized by Ta’ayush, a joint Jewish-Palestinian human rights group from Israel, dozens of Israelis, internationals, and Palestinians came together to build foundations, stone walls, and rooftops for the four rural families of Qawawis and other nearby villages. We mixed cement, formed assembly lines, and broke bread together throughout the beautiful exhausting day. When we were finished I headed back to Hebron.

Windows of Palestinian homes, now encaged, have been shattered by stone-throwing settlers. (Anna Baltzer)

Re-entering Tel Rumeida, soldiers searched my bag and person for weapons. Beyond the checkpoint I could see settler children and their parents carrying M16s home from synagogue. I reflected on the irony of being checked to enter a street where armed fundamentalists known for violence are granted virtual impunity.

One soldier clarified the dynamic for me. He explained, “I’m Jewish, so I have to protect the Jewish people.” I told him I was Jewish too, but that security could only come from protecting everyone’s rights. His eyes lit up when I said I was Jewish:

Settler graffiti reading “Gas the Arabs!”, spray-painted on the doors of a local Palestinian home. (Anna Baltzer)

I told him we’d have to agree to disagree on that one. The exchange reminded me that many of the soldiers patrolling Hebron are settlers themselves. Many of the guns used to terrorize Tel Rumeida Palestinians are from the Israeli Army, purchased from American weapons manufacturers with my own tax dollars.

It is always tempting to blame Israel’s sins on fundamentalist Jews that most Israelis don’t agree with anyway. But the reality is that Jewish-only settlements and outposts could not be established or maintained in the West Bank without Israel’s political, financial, and military support. The Israeli government, whose job it is to enforce the law, instead enjoys a functional symbiotic relationship with the ideological settlers. Both have a strong interest in controlling as much West Bank land as possible, with as few Palestinians on it as possible. As the Alternative Information Center puts it, “the core issue is Israel’s tacit cooperation with the fundamentalist settlers for its own colonial goals: 1. To exploit resources … [,] 2. To expand Zionist control … [and] 3. To realize military and strategic advantages …” The AIC sites four main methods employed by Israel for land confiscation in the Occupied Territories: “the seizure of land for military needs, the designation of land as ‘state land,’ the definition of land as ‘absentee property,’ and expropriation of land for ‘public needs.’ All these methods serve a single purpose: the transfer of land from Palestinian to Israeli ownership.”

This trend of cooperation has been true for administrations of both major Israeli parties. As the foreign minister under Yitzhak Rabin’s first government, Yigal Allon of the “left-wing” Labor party offered substantial political support to settlements in the east Hebron area, trying to prevent Palestinian development in sections of the West Bank that were to be incorporated by Israeli according to the Allon Plan. Having too many Palestinians on certain coveted sections of the West Bank could threaten the “Jewish character” of Israel when they were eventually annexed.

Of course, Hebron’s radical settlers have generally been allied with the right-wing Likud, which along with Labor has facilitated the settler strategies of establishing facts on the ground and attacking Palestinian residents. Israel has stationed 4,000 of its soldiers at checkpoints and military outposts throughout the city of 150,000 in order to protect the 500 settlers. Palestinians are closely monitored while soldiers frequently fail to intervene in settler attacks against Palestinian civilians. In addition, the army often imposes curfew following settler attacks so that the settlers won’t fear retaliation. Curfew only applies to Palestinians. Their Jewish neighbors, who often perpetrated the crimes prompting the curfew, are free to wander through the Palestinians’ streets and land.

If Palestinians manage to leave their homes and wish to register complaints at the police station, they have been prevented from entering by soldiers and police, who commonly dismiss charges directed towards settlers. In fact, settlers in Hebron are subject to a different legal system altogether from their Palestinian neighbors. Jewish settlers are subject to Israeli law, while Palestinians are subject to military law. Therefore, they have different rights and face different legal consequences for the same crime. In every scenario, the Israeli penal code is more lenient. Settlers -— if tried at all, a rare occasion -— frequently enjoy even lighter sentences than usual. For example, a settlement leader Rabbi Levinger spent just ten weeks in jail for killing an unarmed Palestinian merchant, while a Palestinian convicted of manslaughter could face life in prison. According to the AIC, “Israel is violating the principle of equality before the law by creating a situation in which ethnic identity determines the applicable legal system.”

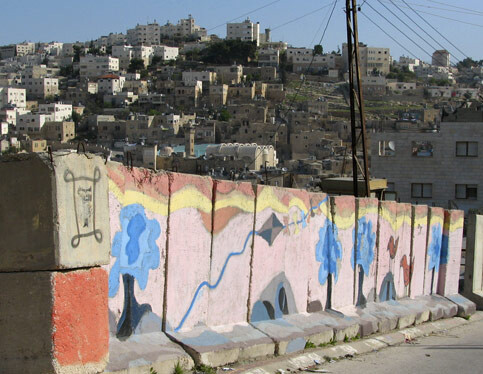

Murals painted by Palestinians line the walls cutting off Tel Rumeida from the rest of Hebron. (Anna Baltzer)

Tonight around the dinner table, internationals who had stayed in Tel Rumeida throughout the Sabbath while we were in Qawawis discussed which incidents of the day to include in a report. Volunteers didn’t think it was worth mentioning that settlers had spit at Palestinians and trespassed on Abu Haykal’s land, because such incidents are so common. They did report on the group of settler kids that attacked four seven to eight-year-old boys who were leaving school with sticks and stones, while border police prevented internationals from intervening.

As we spoke, I kept thinking about Nablus. Jewish fundamentalists once tried to set up camp in Nablus city but they were driven out by the city’s armed resistance. It was one of the few victories of the Second Intifada. What would have happened if the people of Hebron had taken up arms back in 1967 when the settlers arrived? Nablus fighters are called terrorists, and Hebron’s would surely be as well. Still, knowing now what wasn’t known then, could we really blame them? These were the thoughts swirling through my head tonight as I prepared to return to my relatively peaceful existence in Haris.

Anna Baltzer is a volunteer with the International Women’s Peace Service in the West Bank and author of the book, Witness in Palestine: Journal of a Jewish American Woman in the Occupied Territories. For information about her writing, photography, DVD, and speaking tours, visit her website at www.AnnaInTheMiddleEast.com

Related Links