Challenge 4 January 2007

The Israeli-Palestinian conflict was once the mother of all problems in the Middle East. Today it is one among many. For this demotion we may largely thank US President George W. Bush and his war in Iraq. Apart from splitting that unhappy country into Shiite, Sunni and Kurdish sectors, Bush’s war has changed the geopolitics of the region. The Iraq of Saddam Hussein used to be the area’s major power, but today it is Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s Iran. Saddam was a secular dictator who represented Arab nationalism; Ahmadinejad represents Shiite fundamentalism — and his country, of course, isn’t Arab.

In Bush’s new Middle East, then, two axes have emerged. There is the American axis, which includes Fouad Siniora in Lebanon and Abu Mazen in Palestine, along with older members: Israel, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Egypt. Over against them, in the Iranian axis, stand Hamas, Hezbollah and Syria. Does the Iranian axis aim to become America’s global opponent, like the Soviet Union in the Cold War? No. Apart from the central role of Islamic law in Iran, this axis presents no counter-agenda, political, social or ideological. Iran and its allies would prefer to have American and European recognition, but they aren’t willing to change their spots: they aren’t willing, that is, to become American lackeys, eradicating their own identities. They are encouraged in this self-assertion by the weakening of the US as a global power, thanks again to its entanglement in Iraq.

If we want a good example of lackeyism, we may look to Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert. In a recent cabinet meeting, he justified his rejection of Syrian peace overtures, saying that a positive response was forbidden at a time when President Bush, “the most important strategic ally of Israel, opposes any negotiations with Syria.”

The two axes confront each other at three flashpoints: (1) Iran, which opposes the world on the nuclear issue while backing Syria, Hezbollah, Hamas and the Shiites of Iraq. (2) Israel/Palestine, which includes not just the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but now also that between Fatah and Hamas. (3) Lebanon, where the opponents of Syria’s interfering hand are at odds with those who eat from it, namely Hezbollah.

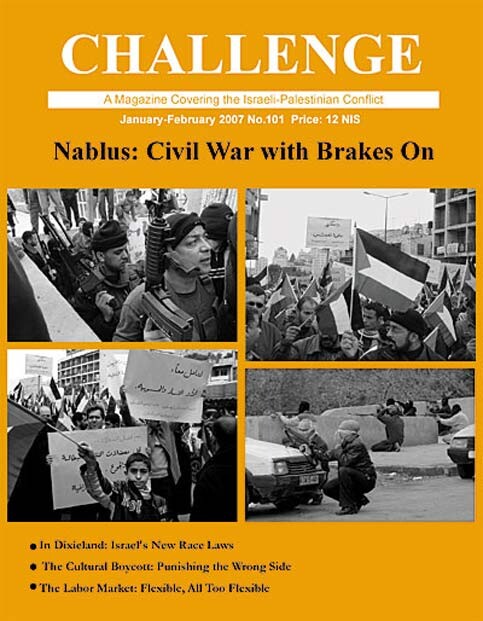

The last two flashpoints may be characterized as civil wars with the brakes on. Each wavers before the point of no return. Up front we see political assassination and shooting in the streets, while behind the scenes the reconcilers toil to patch things up.

In the Occupied Territories, Hamas and Fatah want desperately to avoid civil war, but neither is willing to yield. Nearly a year has passed since Hamas won the parliamentary elections, but the only progress has been in poverty and violence. The trap was already set when Hamas decided to run in those elections, which took place within the framework of the Oslo Agreement. Its landslide victory placed it in a contradiction. On the one hand, it had to form a government reflecting the majority. This majority’s vote for Hamas, however, had been mainly a vote against the corruption in Fatah. The vote did not signify a desire to forgo the funds donated by the international community, which backs Oslo. Yet that has been the effect. For Hamas rejects Oslo. It refuses to recognize Israel. It has become indeed the government of the Palestinian Authority (PA), but it rejects the principles on which that Authority was established (as it must if it wants to continue being Hamas). The donor nations have responded, of course, by withholding funds. In consequence, the workers of the PA’s huge public sector, including many Fatah members, have gone unpaid for months. This has led Fatah to want to oust Hamas, sparking the current battles.

Since last spring there have been intermittent talks between Fatah and Hamas about establishing a government of technocrats, which would be headed by a figure agreeable to them and the donor nations. Under such an arrangement, each side would understand its limitations, while civil life would be able to proceed in a semblance of normality. These negotiations have capsized many times. They started again after the Lebanon War. The agreement was almost readyùeven approved by Hamas’s recalcitrant political leader, Khaled Mashalùwhen PA Prime Minister Ismail Haniyeh embarked on a journey to the Arab countries and Iran. On reaching Teheran, he forgot the agreement with Fatah and began to sing Ahmadinejad’s tune. In return he received a pledge of $250 million. PA President Abu Mazen, seeing that the agreement had again come apart, took a step over which he had long been hesitating: on December 16, he called for new elections. This re-ignited Gaza, setting off more kidnappings, mutual assassinations and street fights, which on occasion spread to the West Bank too.

What exactly did Ahmadinejad whisper into Haniyeh’s ear? Did he tell him that for a few million bucks it wasn’t worth giving up holy Muslim land that the Zionists had grabbed? Did he tell him, perhaps, that he would soon have the Bomb, and then the balance of forces would change? Or did he ask him to be patient until Bush leaves office and the Democrats take power? Woe unto Haniyeh if he has accepted Ahmadinejad as a counselor. The Iranian people understand — as we see from the results of the December elections — that their hard-line president is leading them into an unnecessary confrontation with the world.

The main stumbling block for Hamas, however, is its own attempt to impose religious principles on the conduct of political life. It toys with the illusion that some third party can mediate a ceasefire with Israel, obviating any need to recognize and negotiate with the Zionist state. This illusion spells disaster for the Palestinian people.

If the violence in the Territories benefits anyone, it is Israel. The confrontations between Fatah and Hamas provide it with a pretext not to take a political initiative. Recently, Olmert invited Abu Mazen and his entourage to dinner at the Prime Minister’s residence. This was their first official meeting since Olmert took office, but it was done for form’s sake only. Bush had asked Olmert to thaw things a bit. Olmert agreed to release $100 million in Palestinian taxes that Israel had collected (in accordance with Oslo) and should have delivered long ago. He also agreed to remove 27 of the 522 checkpoints. Against the background of the street battles underway in the Territories, Abu Mazen appeared like a vassal, weak and pathetic. Both he and Haniyeh have been reduced to the level of beggars — one by his patron in Teheran, the other by his in Washington and Tel Aviv.

The new low point in the Middle East has not been dictated by reality. It exists because fundamentalist Islam has penetrated into the leadership vacuum left by corrupt regimes. If we look to Latin America, a continent that was the victim of US economic hegemony in the 1990’s, we can see new hope. We witness the rise of secular, social-minded alternatives to Washington’s lackeys. For all the populist antics of Hugo Chavez, Venezuela’s socialist president, the fact remains that the country’s oil resources are being used to finance health services, lower food costs, provide free education, build housing and make agrarian reform. This is quite a contrast to oil-rich Saudi Arabia and Iran, which support fundamentalist movements that perpetuate ignorance, isolation and poverty.

The choice facing progressive forces in the Middle East need not be between Washington and Teheran. There is room for a third alternative: a system enabling a just distribution of the world’s resources. Until we can bring this alternative to bear, we shall continue to live and die as on a darkling plain, amid the turmoil of unnecessary wars.

CHALLENGE is a bi-monthly leftist magazine focusing on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict within a global context. Published in Jaffa by Arabs and Jews, it features political analysis, investigative reporting, interviews, eye-witness reports, gender studies, arts, and more. This article first appeared in Challenge #101 and is reprinted with permission.

Related Links