The Electronic Intifada 10 February 2023

Israel’s repeated attacks on Gaza make trauma inescapable.

APA imagesI started my mental health journey a few years ago.

From the time of Operation Cast Lead – Israel’s major attack on Gaza in late 2008 and 2009 – I have felt haunted.

My dad received a phone call during that offensive from someone working with the International Committee of the Red Cross.

The caller told us that we would have to evacuate our home within five minutes. Israel was about to bomb it.

Although the bombing of our home did not materialize, I have felt that I am running for my life ever since then.

I have talked about the experience at length in counseling sessions. Yet not only has the feeling never left me, it has become much more intense.

Following another Israeli offensive against Gaza in 2021, the feeling was accompanied by a more general sense of anxiety.

My mom Halima had a panic attack during that offensive.

She called me from Gaza and said, “There is shelling everywhere. They want to kill us all. We will die soon.”

She urged me to do something to save their lives.

I have kept going to my therapy sessions because all I want is to feel well in my mind, body and soul. Despite the sessions, my problems remain acute.

Unbearable pain

I have begun having an unbearable pain in my gut, along with other unpleasant symptoms: numbness in my arms, a lump in my throat, loss of appetite, digestive problems.

I have gone to see a total of seven specialists in Belgium, where I now live.

Most of them told me the same thing: “You’ve been exposed to so much trauma and distress.”

As a result, I have been diagnosed with damage to the vagus nerve.

Running from the brain stem to part of the colon, it is the largest cranial nerve.

The “rest and digest” functions of the body depend on it. The nerve carries signals between the brain, the heart and the digestive system.

The damage has put my body in a constant state of “fight or flight.”

The messages sent from the brain to the digestive system have been distorted. That explains the symptoms I have encountered.

After many consultations, my gastroenterologist recommended a low dose of antidepressants. The aim is to increase the serotonin levels in my body and thereby reset the functioning of the vagus nerve.

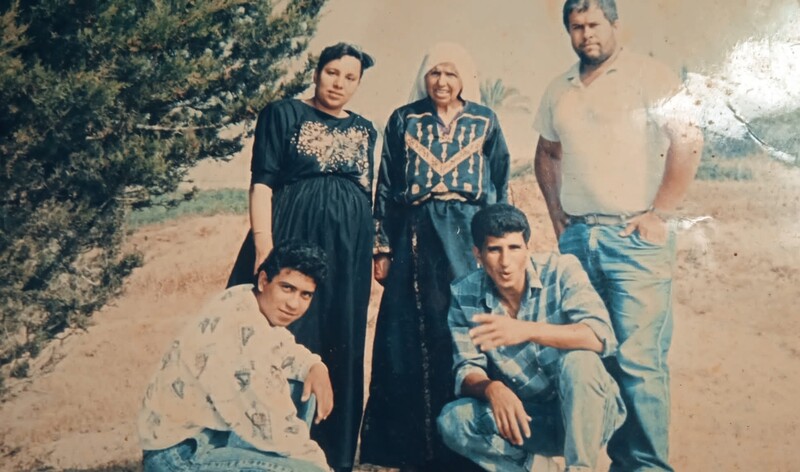

Tamam Abusalama’s mother and paternal grandmother, along with other members of her extended family. (Photo courtesy of Tamam Abusalama)

When I told my mom about the prescription I have been given, she informed me that she had similar treatment in the past.

“I also took antidepressants for six months because I was having so much pain in my back and shoulders,” she told me. “And I was losing a lot of weight. I was feeling disconnected from reality and had no desire to do even basic things. My arms were always very numb.”

Astonished

The strong resemblance between our symptoms astonished me. I was particularly taken aback by how she, too, had experienced numbness in her arms.

I told her that I thought it was amazing that we had felt the same things in the same parts of the body. Yet my mom was not shocked or surprised.

“It’s normal,” she said. “You are my daughter. I carried you in my womb and raised you despite all the hardships here.”

I asked her what exactly she meant by using the word “hardships.”

She replied by referring to how my dad had been imprisoned by Israel for 13 years.

“He was prevented from being by my side when I was pregnant and gave birth to your brothers and sisters,” she said. “I was constantly worried about him and wondering if we will ever have a normal family life. I had to be strong. I had to take care of you while also writing letters to him and visiting him in prison.”

Learning about my mom’s past brought back memories of stories my paternal grandmother shared with us. Stories about the Nakba, the 1948 ethnic cleansing of Palestine.

“We left our home in the village of Beit Jirja, running,” my grandmother said. “We had no time to get any of our belongings. I carried your uncle Khader on my shoulders and your uncle Muhammad around my waist. We walked all the way from the village to Gaza City.”

My grandmother was called Tamam. I am named after her.

She was a charming and resilient woman who had survived the brutality of British rule in Palestine, the Nakba, two intifadas and numerous Israeli acts of aggression toward Gaza.

But she was not invincible. Nobody is.

Afraid

Whenever Israel was attacking Gaza, she would get very anxious.

During the Israeli invasion of southern Gaza in 2006, we could hear the tanks from our home clearly. They made a loud screeching sound.

As the tanks got close to our home, my grandmother went to the kitchen and collected all the knives. She then buried them in the garden because she was afraid the Israeli army would come into our home and stab us with our own knives.

Years later, our gardener found the knives in a gunny sack. They were buried in the soil.

My grandmother had two rules for us when we were little children who wanted to play everywhere and all the time.

Never play on the rooftop. And never play at night.

She was afraid that if we didn’t follow her rules, we would be targets for the Israeli occupation.

My mom explained to me once that my grandmother had always been afraid of Israel’s soldiers “but she never showed it when confronting them.”

“Your grandmother spent her youth running after her five children, who were serving sentences in Israel’s jails,” my mom said.

My paternal grandmother had a total of seven children. At one point during the first intifada, five of them were imprisoned at the same time.

“She had a tiring life,” my mom added. “Yet she gave everything that she had to Palestine and her family.”

My direct experiences are a big part of what I am.

I was born in 1993, the year of the Oslo accords. They were hailed as a peace deal in the international media but proved disastrous for Palestinians.

I belong to a politically active family and I witnessed the second intifada, the imposition of a total blockade on Gaza and Israel’s repeated attacks.

But that is not the whole story. My recent health issues have made me aware of how wounds inflicted on my family – through Israel’s colonial aggression – have been passed on to me.

I have become mindful, too, that Western therapists who treat Palestinians do not see the full picture. By focusing on current events, they fail to deal with intergenerational trauma.

The journey I have undertaken should serve as a wake-up call to mental health professionals.

They need to address a range of issues: both present-day and historical trauma and the way that trauma is passed on from one generation to the next, collective and individual loss and all the resulting symptoms.

The mainstream media and the general public need to wake up, too.

They need to stop pigeonholing Palestinians. We should not be regarded as heroes, villains or victims.

Palestinians are ordinary people living under a settler-colonial regime and forced to fight for freedom, justice and dignity.

No matter how much we work on healing our trauma, the liberation of our homeland is the only way that we can truly heal ourselves, as individuals and as a community.

Tamam Abusalama is a Palestinian communications professional, living in Belgium. Her work includes campaigning for refugee rights.