The Electronic Intifada 4 January 2006

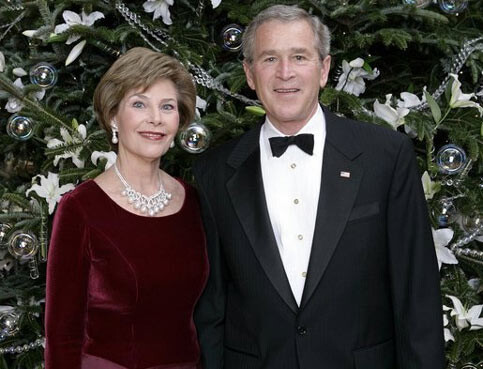

President George W. Bush and Laura Bush stand before the White House Christmas tree in the Blue Room of the White House. In keeping with this year’s theme, “All Things Bright and Beautiful!” the Fraser fir is decorated with fresh white lilies. (White House/Eric Draper)

New Year good wishes have taken on a customary character, which means it can be hard to attach real expectations to them. Yet the new year is a moment to wish and campaign for meaningful change in the way the world is. And despite the breathtaking enormity of human progress, there remains too much to wish for still in terms of ending violence, injustice and poverty.

For our region I have three specific wishes which if realised, would contribute substantially to a safer and better-managed world.

The first is that 2006 be dedicated to the resolution of the Arab-Israeli conflict once and for all. If that seems like an extravagant wish, it is precisely because both the obstacles to peace and the benefits of achieving it remain enormous.

Virtually all the global problems that currently preoccupy Western leaders would be positively affected by serious, genuine progress towards peace. The US would begin to see the hostility generated by its support for Israel in the Arab and Muslim world recede, making international cooperation generally more productive and easy. Terrorism and radicalisation would certainly diminish and Israelis could, for the first time, begin to experience the normality they have long craved but never achieved through military might.

Genuine peace based on justice might even be a catalyst for democracy in the region, because if it commands popular support, regimes would be able to conduct relationships with Israel and the US without the need to suppress currently existing popular opposition.

While making such wishes, one should not remain oblivious to the huge obstacles that lay in the way of their fulfilment. Israel wants to exist in peace within recognisable borders, with normal relations with the entire Arab world, and with no terrorism and no threats to its citizens. This can only be achieved by a just political settlement. Such a settlement requires Israel to abandon the mentality of seeking peace and accommodation while continuing, at the same time, to pursue a policy of expansionist colonisation of Arab lands, ignoring the legitimate rights of the other side and constantly violating international law. It requires, as the beginning, a complete end of the Israeli military occupation of Palestinian and Syrian lands that began on June 4, 1967.

Yet the chances of Israel changing course without external pressure remain close to nil, as Israel talks about peace while accelerating the construction of settlements across the West Bank and turning post-“disengagement” Gaza into a giant concentration camp which it bombards from the perimeter. Unfortunately, there is no reason to expect any diminution of the unlimited support Israel gets from the United States, and there is little prospect that other actors, like the EU, will provoke a confrontation with Israel and thereby directly challenge Washington.

This wish, then, may remain out of reach, but we could yet be surprised.

The second wish is to see the end of the war in Iraq by ending foreign occupation. Euphemism apart, the presence of over 140,000 foreign forces on Iraqi soil is clearly doing little to provide security and normality for Iraqis and much to provoke the insurgency and resistance.

President George Bush is perfectly right to insist that any withdrawal short of total victory may hand the insurgents, or as he likes to call them, terrorists, a victory. But as the insurgency continuously defies predictions that it is in its “death throes”, the US definition of victory seems increasingly vague and changes shape all the time to accommodate the latest setbacks.

It is possible that any abrupt withdrawal of foreign forces may lead to increased violence in the short term by encouraging the many armed factions to consolidate political gains, but the continued presence of foreign forces is a primary factor in fuelling the insurgency. The vicious cycle has to be broken somewhere. Increasingly the US policy in Iraq resembles the doomed strategy of a gambler who having lost his family savings in the casino, keeps borrowing money hoping to win back his position or at least postpone for a little longer having to return home empty-handed to face the consequences of his disastrous choices.

It is possible that the American public, unwilling to continue paying the price of this war, may force the government to begin to withdraw. The campaign for the 2006 mid-term elections in November 2006 may see developments in this direction.

The third wish, related to the first two, is that the power of international law be restored. This has been seriously threatened by the lack of any constellation of forces that can restrain US unilateralism and will to impose its hegemony. The trend towards international anarchy has been exacerbated by the collapse of the Soviet Union which balanced and restrained the exercise of American power.

The end of the cold war was a moment when the United States could have used its unprecedented power and prestige to strengthen the system of international law and multilateral institutions which it was so instrumental in founding after the two world wars. Instead, the US has undermined international law through selective application — using it and the UN merely as instruments in an arsenal to be used in the pursuit of its own narrowly defined interests. A major factor in exposing the weakness of international law has been the long-term policy of American administrations to veto any enforcement of international law when it comes to Israel’s universally acknowledged violations.

No law is respected if not properly and universally applied. This should be addressed, and if progress is made towards ending the conflicts in Palestine and Iraq, it would pave the way for reforming the UN system and restoring its credibility by ending the massive double standards in which no one dares enforce UN resolutions if it means confronting Israel or restraining the US.

The revelations in 2005 about the American use of torture and extraordinary rendition, with European collusion, demonstrate that no states, no matter how law abiding they claim to be, can be completely trusted when their behaviour is unregulated by international norms and laws.

It remains an inescapable reality that the United States is the world’s sole superpower. But the Iraq war has shown the opposite of what the US perhaps intended: America is not all-powerful or able to act wherever it wishes alone. This ought to be a lesson to other governments: if they have the foresight and work together, they can nudge the US to move in the right direction. If that begins to happen, all these wishes may not seem so far-fetched.

EI contributor Hasan Abu Nimah is the former permanent representative of Jordan at the United Nations.