The Electronic Intifada 12 June 2025

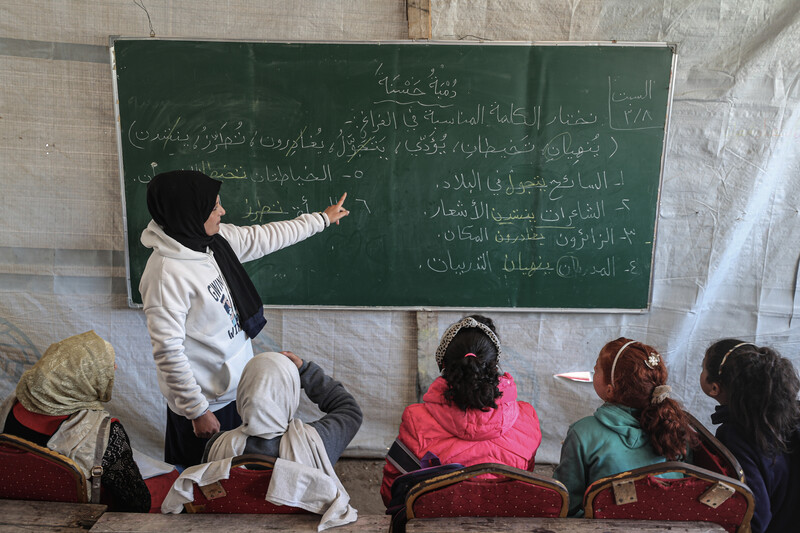

An educational tent in Jabaliya, northern Gaza.

APA imagesI felt at ease for the first time in what felt like forever on 19 January as a ceasefire agreement in Gaza was finally implemented.

I’m a student who was deprived from continuing her degree in education studies for nearly a year after October 2023.

Before this genocide erupted, I used to volunteer as a teacher for children.

Israel had killed at least 12,400 students and directly hit or damaged 88 percent of the schools in the Gaza Strip by January 2025, leaving about 658,000 students without formal education.

I felt responsible as a teacher.

I decided that the moment my family and I return to Jabaliya in northern Gaza, I would establish an educational tent where children could study for free.

I didn’t want the children in my neighborhood to be deprived of an education – as I once was.

My family and I returned to Jabaliya a week after the ceasefire. We had been displaced to the west of Gaza City after Israel bombed our home in Jabliya in November 2023.

Of our five-story building, only the first and the second floors were left intact.

My family and I repaired the remains of the first floor and moved back in while my uncle settled in the second floor.

Two days later, I went to a camp just a few meters away from our house. It was being set up to provide tents for people who had lost their homes.

I approached the camp administration – the men in charge of managing the camp – and shared my idea of establishing an educational tent. They welcomed it as there were no schools.

At the beginning of February, I returned to begin implementing the idea, but the administration explained that there was no space left. Due to the widespread destruction, many families had already settled in the camp.

I felt devastated.

I returned home in tears and told my father what had happened.

He gently placed his hand on my head and promised he would find a solution.

The next day, the camp administration called my father to inform him that we had been assigned a shelter tent since our house was bombed in November 2023.

My father told them that we had managed to repair part of our house and would live in it – so we could turn the shelter tent into an educational one instead.

My heart soared with hope.

I immediately went to the camp and asked Islam, a 10-year-old boy I knew who lived there, to tell his friends that we would soon be starting classes.

Together, Islam and I gathered around 100 students from the first, second and third grades.

Sanctuary

On 3 February, at around 7 am, I began my first day of teaching inside the educational tent.

I welcomed the students warmly and introduced myself as their teacher. As an icebreaker, I asked each student to stand up, say their name and share something they were good at.

When it was the turn of Ahmad, 12, he stood and said he had a beautiful voice and would sing. He began a song, one we often dedicate to martyrs:

The moon has slumbered, but our longing will never sleep

And our tears at night echo to him our salaam.

We could hear the emotion in Ahmad’s voice as he sang.

Yet some of the students responded in an inappropriate manner.

One of the students laughed, and soon others joined in.

Ahmad burst into tears and furiously shouted at his classmates to stop laughing – his father was a martyr who had been burned alive. Ahmad was so upset that he threatened one of the students.

I quickly stepped in, asking the students to apologize to Ahmad. Then I gently told him that I wanted to speak with him after class.

The tent fell silent.

One student, Anas, quietly said that his father was also a martyr. Two other twin girls, Sama and Sila, added that their father had been killed too.

I asked the class how many had lost their fathers. Twelve students raised their hands and began sharing how their fathers had been killed – most when the Israeli army invaded Jabaliya in October 2024.

The weight of their grief overwhelmed me. At that moment, I realized this tent would be more than just a place for learning – it would be a sanctuary for healing.

I sat with Ahmad after class and asked him to share his story.

In mid-October 2024, Ahmad and his family were trapped in Jabaliya under a hermetic Israeli siege.

For five days, they had no food or water. Ahmad’s father left to search for something to eat or drink at a nearby neighbor’s home.

While he was there, the Israeli army bombed the house.

Ahmad’s father screamed for help as flames engulfed the house. But no one could reach him – Israeli quadcopter drones were firing at anyone who came near.

Twenty minutes later, the father’s voice went silent.

Ahmad’s own voice cracked as he told me he could do nothing to save his father as he burned.

I placed a hand on his shoulder and told him that his father is now in a better place.

I reminded him that through patience and success, his father would be proud of him – even in his death.

“You’ll be our class leader,” I said. “But you must promise never to threaten anyone again, and instead focus on your studies.”

Ahmad gave a small smile and promised to do better.

He began helping me clean the educational tent and organize the students.

His negative attitude turned to a positive one over time.

But Ahmad’s story wasn’t the only heartbreaking one.

Majd, another 10-year-old student, often drifted away during lessons, silent tears falling down his cheeks.

I would sit with him after class, and he would tell me how much he missed his father.

Majd’s father had stayed behind at a friend’s house in Beit Lahiya.

Majd, his sisters and their mother sought refuge – first at their aunt’s house in Jabaliya, and later in western Gaza City, relocating in late November 2024.

They stayed in contact with his father until 20 December, when all contacts with him were suddenly cut.

When the ceasefire took effect on 19 January, the family returned to Beit Lahiya to search for him.

But the house where he had taken shelter was reduced to rubble.

They called his phone over and over. It remained off.

Hours later, a family friend told them that Majd’s father had been martyred in December 2024.

Tears streamed down Majd’s face as he told me the story.

“I miss my father so much,” he said.

I encouraged Majd to write letters to his father – to pour out his heart in words.

I also gave him small responsibilities, like collecting students’ notebooks and erasing the board, to help keep him engaged.

When I first established the educational tent, I never imagined the depth of the wounds I would encounter.

I never imagined I would be teaching so many orphans.

I am not only helping my students rebuild their knowledge in this tent. I am helping them rebuild hope.

Ohood Nassar is a writer currently finishing her degree in education studies in Gaza.