It was a very long plane ride. Seven hours from USA to Frankfurt, spending a few hours at the airport, then changing to another plane bound for Tel Aviv. Though Palestine is my homeland, I haven’t been back for five years. The last time I visited, in 1999, was at the height of the Oslo “Peace Process”. Everyone there was optimistic, hopeful that a decades-old conflict will come to an end so they can get to enjoy normal lives for once, like the rest of humanity. Many emigrants had returned, and Ramallah, thought to be a de facto capital of the future Palestinian state, was booming.

This time I didn’t really know what to expect. The high point of peace had lasted only briefly, with the region slipping back into a violent conflict, erroneously labeled “Intifada”, after Sharon’s offensive entry into the Aqsa mosque. Over the last three and a half years, I have seen countless violent and horrendous images on TV. On CNN, I have been able to follow for several hours the gory aftermath of the occasional suicide bomb in Tel Aviv. On BBC and later, al-Jazeera, I have been able to follow the never-ending stream of horrific Israeli attacks on Gaza and the West Bank, against my own people, friends, and family.

My heart would jump every time I heard there was an attack on Ramallah, picking up the phone immediately to call my parents and check on their safety. My heart would jump too when I hear of a suicide bomb in Jerusalem, because then I know that a “reprisal” Israeli raid will likely follow. One time I heard Israeli Apache helicopters were bombing some Palestine Authority office in Ramallah, about 100 yards from my parents’ house. I called home. My aged mother answered the phone. My dad was outside working, and she was alone. The electricity to the whole city was knocked down by the bombing, and my mom couldn’t reach any candles from her wheelchair. I could hear the sounds of the bombing from the telephone.

Traveling with me, and not knowing what to expect either, was my wife of four years. She is neither a Palestinian nor an Arab, and has never been to the Middle East before. I longed to take her to visit my home country. Since the present Intifada erupted, various reasons forced us to keep postponing the trip. Despite my reassurances, she of course worried for her safety. My own secret fear, however, was her getting a negative first impression of my country when she saw all this destruction and danger. I somehow imagined we would arrive to a Ramallah in ruins - with TV images of Arafat’s bombed-out compound or the Jenin refugee camp imprinted in my consciousness. At first, we kept postponing the trip, one year to the next, hoping that the situation would improve.

Instead, things kept getting worse. Every year became worse than the one before. After the massacre of Jenin and the siege of the Church of Nativity in Bethlehem, Sharon’s government started building a wall, to keep Palestinians enclosed within their cities-turned-prisons. I have seen many images of that wall. It looked very tall, medieval, and threatening. Being somewhat claustrophobic, I dreaded having to come face-to-face with it. What will my reaction be? Yet with events spiraling towards the worst, we finally decided there is no point in waiting any further. “Let’s go visit Ramallah before Ramallah itself disappears from the map”.

Though I have settled in the USA for the last 15 years, I am a Palestinian, a Christian Arab born in Jerusalem in the early 1970s, under Israeli occupation. My parents originally came from the Arab cities of Yafa and Ramleh, now almost absorbed by sprawling Tel Aviv. They both had to leave their homes under fire in April 1948 when the armed Jewish terrorist groups Irgun and Hagannah attacked their cities. Most Arab families at that time were unarmed and city defenses were laughable, courtesy of the policies of a 30-year old British occupation. With their families, my parents fled for their lives and settled in Ramallah, becoming two out of over 800,000 Palestinian refugees who were evicted under similar circumstances.

The following month, the Zionists declared a Jewish state they called “Israel”. Much later, in 1967, Israel invaded its Arab neighbors and took control of the West Bank, completing its control of Palestine, and thus my parents fell under occupation again. Though I was born in Jerusalem, my residence was in Ramallah, and the Israelis made a point to rub that on me, by giving me a special orange ID card as opposed to the blue-color ID for residents of Jerusalem, a city the Israelis consider their capital.

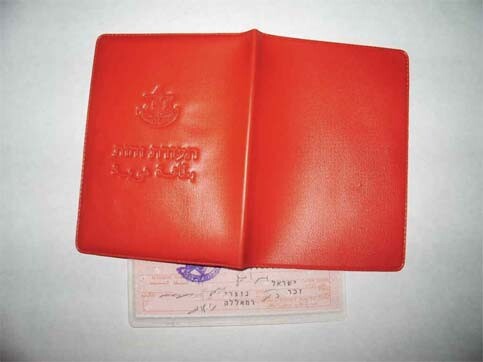

An orange Israeli ID, identifying a Palestinian resident of the West Bank. Anyone caught not carrying his ID is subject to beating, imprisonments, and or fines. “Religion: Christian” says one line on this “yellow Star of David” of modern-day Israel.

You see everything in Israel is color-coded and segregated: different colored-Ids; different-colored license plates; “Arab rooms” in the airport where we get the 4-hour interrogation/strip-search special while Jewish travelers walk through security in minutes; and special foreigner border points across the Jordan river so tourists will not see the day-long torture sessions ordinary Palestinians have to twice endure every time they need to travel abroad through Jordan.

Israelis apparently take pride in their discrimination, proudly informing us at the embassy that my wife is likely to get her Israeli visa application denied “for the reason that she is married to a Palestinian”. How is my wife to visit my birthplace when ethnicity of spouse is a visa requirement? Besides, why would my wife care to visit that war-torn place in the first place were she not married to me? To get her visa, my wife returned to the embassy alone, posing as a tourist staying in Jerusalem and wearing a big cross. This time they gave it to her.

What made the trip much more terrifying is the Israeli assassination of Hamas leader Sheikh Ahmed Yassin just days before our scheduled departure. After long deliberations, hours of watching the al-Jazeera news, and many phone calls home, we had decided to risk it and go. The newspapers served on the plane were not very reassuring, quoting threats from Hamas and suggesting they might retaliate by attacking Tel Aviv airport. What worried us even more, however, was Israel’s planned response if Hamas took the bait and retaliated.

The flight became really uncomfortable as we switched planes to Tel Aviv. Suddenly, I was one of the few Arabs on a flight packed with Jewish passengers. Everyone had a strange look on their faces, as if they were suspiciously eyeing us, our neighbors looking around at us so frequently. An old man sitting next to us, flying by himself, looked sympathetic enough. Twice he asked us to borrow a pen to fill out his paperwork, and twice we loaned him ours with a smile. After we landed in Tel Aviv, while we were waiting for the door to open, he attempted to strike a conversation.

“First time to Israel?” I made the idiotic mistake of saying “no” and little by little he gleaned just enough to figure out I’m Palestinian. He was the first one to exit the plane, and I was right behind him. At the bottom of the steps, a number of airport security guards were waiting. With a nod, this old man said a word to the security guard, and the next thing I know, the guard jumps in front of me, blocking my way. For the next 15 min., we were interrogated right there on the taxiway, not even allowed to board the bus to the terminal, while everyone else looked on as they disembarked.

Finally at the terminal, the “place of birth” on my American passport and the seemingly innocent question of “How’s your Hebrew” were enough to identify us and lead us into the infamous “Arab Room”, now reduced to a small corner of the airport. Despite our being married for four years, and despite all that she learned about Palestine and the conflict during that time, my wife simply could not believe the way they treated us at Tel Aviv airport. At first she thought they were taking their time checking our passports.

Quickly though, she couldn’t help notice how empty the airport was, and how many of the border girls working there were hanging around chatting and doing nothing, while we were told to wait. After a tiring 20-hour trip, we were made to wait 3.5 hours, with no access to food, before finally being escorted out of the airport, and into an Israeli taxicab that was instructed not to let us get off anywhere except inside the West Bank. He dropped us off at a remote checkpoint close to the airport, but one hour away from Ramallah, in the dark of night, and we immediately had the sinking feeling of stepping into a prison.

Dr. Saber Zaitoun is the pseudonym of a Palestinian-American in his thirties. Dr. Zaitoun grew up under Israeli occupation and first came to the USA during the first Intifada to finish his education. He is married, and currently teaches at a University on the East Coast. For more information about his visit to Palestine, please see www.triptopalestine.com.