The Electronic Intifada 30 August 2018

Sanabel, 14, works on her lesson using a braille typewriter during a class at the Peace Center for the Blind in occupied East Jerusalem.

The streets in occupied East Jerusalem were only just starting to get busy, as the morning sun began to heat up for the day. But already Lydia Mansour was sitting on the couch in her office at the school she directs, fielding calls on two telephones and making plans for getting her students home for the summer.

The smell of fresh coffee was thick in the air, and the sound of children squabbling could be heard from the hallway outside.

“There is so much to do, I need to contact the parents, schedule cab rides and prepare for the boarding house to be cleaned. The older I get, the more it seems like I need to do,” Mansour said as she sipped from a steaming cup of coffee.

“Something different”

Mansour, or “Miss Lydia,” as her students know her, has been blind since the age of 2 some time before the 1948 Nakba of which she still has vivid memories (she declined to divulge her exact age).

She is the founder and director of the Peace Center for the Blind, a school and vocational center in the Shuafat neighborhood of East Jerusalem that caters to blind and visually impaired Palestinian girls and women and includes a boarding house for those from elsewhere in the West Bank.

All the residents of the boarding house are girls and women and both staff and students live on the premises. During the school year, the house is home to nearly 20 students, all sharing a large dorm-style room.

Mansour knows first hand the difficulties that visually impaired people face in society, part of which still stigmatizes those with disabilities.

After retiring from her job with a British Christian charity for the blind in Jerusalem in 1981, she heard of two teachers let go by their employers because they were blind. She also heard stories of blind students being teased by their peers and instructors. These stories upset Mansour deeply and awoke something within her. Instead of retiring as she had planned, she felt an urgent calling to do something bigger.

“The lord said: Now you have to do something different. And I listened.”

Building a community

The Peace Center for the Blind was founded in 1983 with donations that Mansour and neighbors collected. With a total of $200, she managed to secure a location and pay for rent.

The school – which is registered with both the Israeli and Palestinian ministries of education – serves to give blind girls an education, culminating in the tawjihi, the national exam that 12th grade students must pass under the Palestinian curriculum to graduate from secondary school.

It also provides older women a chance to learn vocational skills such as stitching and loom weaving. Education is provided by qualified teachers and instructors and the school has braille textbooks for its students.

Located less than a mile from the school in another part of the Shuafat neighborhood is the boarding house in which the students and Mansour live. The house is another key to the school’s ethos. There, students live, eat and play together, and learn to take care of the small garden on the property.

“Being together all the time teaches the students self-care and social skills. Many of the students arrive and are very lacking in how to behave and live with others. At the boarding house and the school they build a community,” Mansour said.

One student, Muna, 14, was particularly difficult to handle when she first arrived.

“She would fight with the other girls, refused to participate in any activities, and had no idea how to take care of herself when she first arrived,” Mansour said. “But now she is a model student. She loves playing with the other girls in the boarding house and is excelling in her studies.”

Transformation

Muna’s story of transformation is one of many. Past students to the school have returned to help run the boarding house, cook and even teach current pupils.

“We believe not just in educating, but in really having a lasting impact on our students. We hope to foster a community that they will stay connected to throughout their life,” Mansour said of the school.

The boarding house has become ever more important over the years as Israeli restrictions on freedom of movement have tightened. With checkpoints across the occupied West Bank, proper paperwork and coordination must be made between the parents of the students and the school every year for the holidays.

From simple beginnings, when Mansour worked alone, teaching, securing funding and caring for her students’ needs, the school has expanded. Funding from international organizations allowed the school to hire more staff and take in more students.

The school, however, has come up against hard times in the past few years. A major donor, that Mansour declined to identify, cut funding to the school and now faculty are having to find alternative ways to raise money for rent and other costs. For the past two years, the school has been operating on reserve funding.

“I fear that we may soon have to close our doors if we cannot afford to fund the school next year. It is in God’s hands though, and if He is willing we will continue our mission,” Mansour said.

She said she was hopeful that money raised selling knitted sweaters and socks and other merchandise produced at the school would help cover some of the donations that have been lost until more donors are found.

Matthew Hatcher is an American freelance photojournalist currently documenting life in the occupied West Bank.

Teachers and students outside of the Peace Center for the Blind boarding house on 1 June, the last day of the school year. The boarding house in occupied East Jerusalem is rented by Lydia Mansour, founder and director of the school, and paid for out of funding raised for the school. Students who attend the school and its vocational training program are from the occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem. At the end of the school year, the students return to their homes for the holidays.

Lydia Mansour, the founder of the Peace Center for the Blind, closes the doors to the boarding house where the students live in the East Jerusalem neighborhood of Shuafat.

The braille alphabet is the first thing many of the new students to the Peace Center for the Blind learn. The school has a braille library and most of the records kept by Mansour are written in braille.

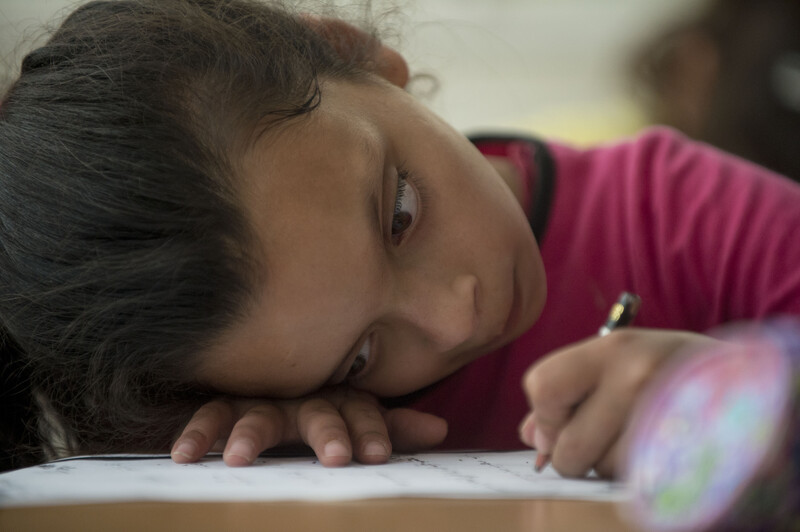

Muna, 14, exits the Peace Center for the Blind for recess during the week of exams. Her teachers say Muna was a “troubled child” when she first came to the school. But they now hold her up as a model student.

Ilham Arabah, a teacher at the school, checks the work of one of her students during exam week at the school. Following exam week, the girls move out of their boarding house in East Jerusalem and return to their homes elsewhere in the occupied West Bank for the summer.

Hala, 10, concentrates on her exam work during classes. She has very limited partial vision. In order to read and write, she and other students like her use bold pencils and must get extremely close to their work.

Surrounded by students and teachers, Lydia Mansour calls parents of her students in order to get them home on the last day of school. Many of the students live in the occupied West Bank outside of East Jerusalem and due to Israeli travel restrictions, the journey home can be difficult and must be well coordinated.

A vocational student learns how to stitch on a machine at the boarding house of the Peace Center for the Blind. The students, who learn to stitch and sew, sell their products to help raise funds for the school to remain open.

Amira, 12, guides Sanabel, 14, down the stairs outside of the boarding house for a meeting in the basement. The students grow close to each other through the school year, often helping each other when needed. “We don’t just teach academics at Peace Center for the Blind,” Mansour said. “Many of the students have poor social skills, and we do our best to teach them how to interact together.”