The Electronic Intifada 8 June 2024

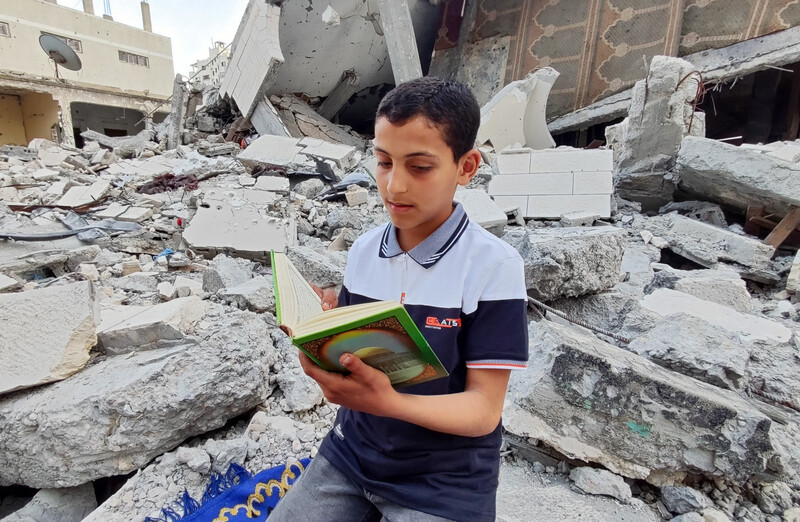

Taking a moment to read in the rubble in Gaza City on 23 April 2024 after an Israeli airstrike on a mosque.

APA imagesWill my family and I – will my people – ever fully heal from everything we have gone through in Gaza?

Even though I have now escaped to Egypt, which has been reluctant to take in those fleeing the Gaza genocide, it is difficult to imagine how long I will be entrapped by the shackles of trauma, the heavy cloak of depression, the relentless grip of silence, the haunting specter of fear, and the ever-present trembling of my spirit.

Anxiety and tension have persistently shadowed me since 7 October. I have come to dwell on the inevitability of mortality.

I know I am far from alone with my worries.

On 19 April, the American Psychiatric Association expressed alarm over the psychological and behavioral consequences that will affect the people caught in the violence since 7 October.

“This crisis underscores the pressing needs of our interdependent world. We must move from anguish and conflict to deeper understanding, compassion, and goodwill,” it said in the statement.

It was during our initial displacement from our home to my aunt’s residence when I first began to feel unease and apprehension encircling me.

On my first night there, I struggled to sleep. I lay my head on the unfamiliar pillow and the cold, rigid bed, surrounded by darkness. There was no electricity, there was no light — and no hope.

I dozed off, but woke up to the sounds of shelling and Israeli warplanes flying above. What was happening I couldn’t determine as there was no consistent access to the internet to keep track of the news.

The situation became more complicated. We started receiving messages warning us to evacuate the area. Where to, we wondered, since the buzzing drones above continuously monitored our movement through the night.

Another displacement followed to another shelter in Khan Younis. I longed for home, but thoughts swirled relentlessly: Will we find safety this time? How will we navigate the town amid all the bombings? How can we possibly survive to reach safety?

The haunting truth is that reaching our destination offered no assurance of salvation.

Hear it and live

Fear at first engulfed me in this unfamiliar refuge: Lights flickered, but they were not the soothing glow that I was used to; they heralded death. As the yellow rocket’s glare and its thunderous crash echoed throughout the city they made many of us feel as if we were about to perish in terror twice.

The rocket we hear doesn’t kill us; everyone knows this. This assurance was shattered when a barrel of rockets fell on our neighborhood. In the rubble, we could not hear the rockets as we lay trapped, uncertain whether we were alive or breathing our last. We could only bleed, unable to lift the stones from our bent bodies.

I had not shed a tear until that moment and when they came, each one felt like swallowing poison. Survival was paramount. All we could do was to scream and shout to make our trembling, fear-filled voices heard, to prevent us from disappearing.

A specter from that night lingers in my mind, haunting my reality, my dreams and my every thought, even though we survived.

The true depth of my shock and the toll of it all became evident when we were displaced again to a new place. Here, for the first time, I began to unravel. Tears began to flow freely, my crying echoing through the room that would become yet another refuge.

The moment I caught my breath in this place, suspended between life and death, I immediately began biting my nails, an old habit that I had long abandoned.

Indicators of trauma

It is difficult to ignore the tension accompanying the constant fear of sudden airstrikes. It’s triggered by the slightest sounds — a chair shifting, a window creaking, a door knocking, the sound of car engines.

I now struggle to connect with those around me, unable to endure someone speaking for more than five minutes. I have lost my ability to listen patiently to loved ones and engage in lengthy conversations. My soul has devolved into someone unrecognizable — a hardened figure, not expressing any emotions.

In consequence, I gravitate towards solitude and isolation but lack the space to fully embrace these feelings.

When I arrived in Egypt after two months under genocide, most of my feelings began to reclaim their space. There were no shellings or bombings, but I was suddenly overwhelmed by waves of unexpected tears. They could come at any time and place.

There is no apparent explanation for these tears, but I know they result from the culmination of experiences I have endured and that I have never been able to properly process.

It is also grief and guilt. I shed tears for the loved ones I’ve lost. I am overwhelmed by feelings of helplessness knowing that my friends are still suffering, still displaced, and dying of hunger.

I lost my home, my work, my life, the projects I planned to work on with a friend I have not heard from in almost four months, as well as my dreams and studies. I could have achieved a lot more had the Israeli aggression not happened. I would have made many more memories in Gaza had it not been for the genocide. My books, school, and university are gone, but they are all alive in me.

I used to be an avid reader, but I have not been able to pick up a book for over six months. My hands, eyes, and mind are unwilling to work with me. I used to easily select a book from my cherished library, now reduced to ashes by Israel. As someone who used to write daily, I find it almost impossible to even begin.

I am more irritable. I have arguments with no cause.

I, who was normally so laid back.

Endless nightmares

I flee from reality, seeking refuge in sleep, only to find that what I try to escape from continues to haunt me.

I see again the barefooted man in tattered, white clothes chasing an ambulance.

“That’s my son, my beloved!”

I hear again the anguished screams of a young man, his hand maimed by shrapnel, reverberating through the area, pleading: “Oh God.”

Awake, I ask friends whether they had ever considered ending their lives and if they knew of a quick and painless method to do so. One friend, trying to lighten the mood with a joke, suggested jumping from the Cairo Tower, as it is a one-way ticket to God.

Over the past many months, I have endured this turmoil to the point that I am incapable of coping with it any longer. As a means of releasing my inner turmoil, I return to writing.

I bought notebooks, wrote everything I had experienced and confronted it on paper. I even read and purchased a few books at book fairs. I re-engaged in social relationships and began discussing my inner turmoil with friends.

I began taking courses and participating in situations requiring confrontation, conversation, concentration, and effort in order to find solutions, in order to survive.

The struggle to heal continues. I remain disconnected from the rhythms of daily life, even though I am attempting to cope.

The longer we continue to live under Israel’s brutal, inhumane occupation, the greater my desire to be free, to achieve the eradication of Israel from our homeland.

Rania Abu Taima is a writer and translator from Gaza.