The Electronic Intifada 6 February 2006

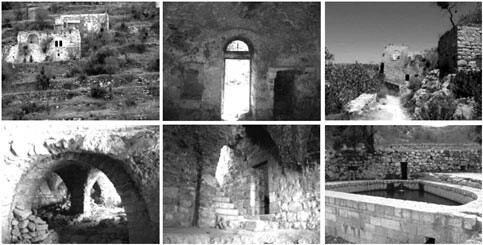

Lifta constructions.

[PREVIOUS]

The “natural” stone - and not the “smooth, chiselled stone” - is the building material allowed in that area, so the nature of the materials used is preserved. The landscape with the terraces will be preserved, as will the trees. Those trees that will have to be uprooted will be re-rooted within the area included in the construction plan. The approach to this space treats it as though it were almost sacred. It is a kind of effort to revive the village after 56 years of destruction, negligence, and natural decay.

Lifta is to be reconstructed from its old materials. It is to be rebuilt around its historic core, as if the centre can somehow radiate the authentic spirit of the place. It seems that in the eyes of the planners, the larger, newer Lifta will be a kind of duplication of the preserved kernel of Lifta’s original houses. Therefore, all of the area included in the plan will be built in the original architectural manner. You could say that Lifta is to be not only preserved, but also replicated - many times over. The wasteland that now exists in most of the area slated for renovation will bloom and be filled with the housing of a new and successful real estate project.

The kernel that stood ashamed and battered will be renovated on all its sides. Here the greater Lifta will be established, a neighbourhood that will provide a great quality of life for the country’s wealthy people. Here, we can see not only the familiar “making the desert bloom” typology, of building where nothing once stood, but also the expansion of constructed Israeli areas: an expansion that does not overlook the history of this place, the terraces, trees, houses, spring, etc. Not only is one Lifta being rebuilt but several duplicated

Liftas will from now on exist down in the wadi, right below the western entrances to the capital. And that’s where it ends. The original Palestinian inhabitants of Lifta are nowhere to be found in the plans. Those who created and cultivated this space, their memories of the village, their exile and longing to return are not mentioned at all. Only a deconstruction of the plan reveals how they were removed. Two thousands of the village’s refugees, who are missing from the plan to rebuild Lifta, live within few kilometres of their lost village. They are not part of the construction plan; or rather, they are only part of the hidden element of these plans, the element that should categorically not be taken into consideration. They are too close to be a part of it.

Lives overlooked

The refugees are still here, together with their descendants, their memories, and their desire that the injustices done to them be acknowledged and repaired. All this, it seems, cannot be part of the new construction plan of Lifta. It is like a bomb that vaporises the human beings but causes no damage to the buildings they once lived in. Humanity is separated from Lifta, and only a mixture of materials remains there.

Turning Lifta into a high-class neighbourhood will also eliminate the marginal culture that developed there, as it is one of those values that a proper Western environment cannot tolerate. Hirschfield interprets the establishing of the artists’ village of Ein Hod as a similar action, in which blindness rules the approach towards the destruction of Palestinian life.

The “naivety of Israeli painting led a group of painters to come and reside inside the object of their paintings. They came to dwell inside the ‘beauty’ of Israeli art which contained within its development process the emptiness and destruction that were at its very basis.”4 This is not just an act of “making the desert bloom” as far as the settlers were concerned, or an act of overlooking the end of the lives which existed before them. Their attitude and action negates the previous human life that existed here.

The Palestinians who lived in Lifta and Ein Hud (before it was renamed Ein Hod) are robbed of their identity by the Zionist settlement venture: nothing was there that we need to face today, let alone in the future. Ein Hod was built, as Lifta will be, on ‘beautiful’ ruins that have no humanity left in them. “Making the desert bloom” is a discursive mechanism through which the lives lived prior to the Zionist enterprise in the country become a mere “mental desert” in Jewish-Israeli awareness.

Yigal Tzalmona sees a similar trend in the paintings of Gutman and Rubin. The country’s landscape, with its Palestinian villages, “carries the characters of the Orient without the presence of its indigenous people. The accepted Zionist perception of the Land of Israel from the turn of the 20th century until the 1920s was embodied in its image as a desolate land, which the Jews who returned to it will turn into a flourishing land.5

“The Palestinian village itself, as seen, for example, in Rubin’s portrait of the sculptor Melnikov, becomes the scenery and backdrop in pictures showing portraits of strong, rooted Jews, connected to nature, to the landscape, to the mountain and to the village - as a sign of indigenousness. The village is empty (of people) specifically because it plays a role as a mark. The Orientals - in this case, the inhabitants of the village - are not needed in the scene, because the human dimension is already realized through the presence of a real person, the portrait of a particular person, a man with a name, a Jew. In the descriptions of the Orient in the 1920s, there is an elevation of the Orient’s features, but without identifying or concretizing with these features through true intimacy.” 6

Similarly, in the construction plans for Lifta, the village’s houses and material remnants function as a natural environment, as a local and Oriental nature whose aesthetics should be benefitted from. This plan is not disconnected in its approach to space from other cultural manifestations of Zionism. In this plan, the void created by the lack of a human, Palestinian, presence is filled by Jewish settlers. One clear expression of this is the plan to build a Jewish synagogue in Lifta (chapter 14, article 1, “area designated for public buildings”). There is also a plan to build a museum there, but there is no sign that the local Palestinian history will be made part of the exhibits.

Plans for Lifta.

One blunt testimony to the eradication of the human in Lifta’s construction plan is the absence of Palestinian cemeteries. In plan 6036, the cemeteries don’t appear at all. They also don’t appear in the detailed cartographic map (1:2,500) that was submitted with the plan. In construction plan 2351, from 1984, the cemeteries are not to be found in the written plan, but are located in the cartographic map. According to the current plan, a “specially preserved residential area” is to be built on the cemeteries. There is no recognition of their presence in that area. So not only are the living refugees, who were forced to leave the village in 1948, absent from the plan, but even the dead who remained in Lifta are not to be mentioned in any way. Once again. preservation applies only to buildings, trees, terraces and landscape, but not to the people, dead or alive, who used to live in Lifta.7

Challenging creativity

In a situation where state ideology is rooted in each plan and masterplan, creating an alternative to the governmental plans is not enough. Our creativity needs to come through the different ways we choose to expose these stories of urgency and through these various means we can succeed in engaging our colleagues worldwide in the design process. The story of Ein Hud was told through a worldwide architecture competition.8 Renovating Lifta is a project through which we hope to engage the worlwide academic community once more. We would like to use this platform to invite architecture, planning, renovation, and preservation faculties to participate in creating a plan for Lifta and submit the results to us. They will be exhibited in Israel in the summer of 2006.

More information can be found soon at www.seamless-israel.org.

Endnotes

[1] Naqba or Al-Naqba: this term, which means “the Catastrophe,” refers to the expulsion of the Palestinian people from Israel as a result of the 1948 war.

[2] Perhaps the best example for this is the refugees of Safuria. Some 15,000 refugees (and their descendents) live in crowded conditions in a neighborhood in Nazareth called Safafra (named after the village.) Though they live today only several kilometers from their lands, they are not allowed to return to it.

[3] Shviki, Itsik; Lifta, The Picturesque Village

[4] Hirschfield, P. 22.

[5] Tzalmona, Yigal; “Eastward! Eastward? On the East in the Israeli Art”, in “, in Exhibition catalog; Kadima - The East in Israeli Art, Tzalmona Yigal and Manor-Fridman Tamar (Curators), The Israeli Museum, Jerusalem, 1998. P. 58.

[6] Tzalmona. P. 59.

[7] Nonetheless, two Jewish families living illegally in the village area were allowed to stay put. During a debate regarding objections submitted over the first construction plan (No. 2351) it was decided to allow Mrs Yekutieli and the Sofer family to continue living in building “in an area which is designated to be an ‘open view area’, allowing them to use it as a residency and a studio…” The committee that responded to the objections actually legalized their residency in the place, even though they don’t have an original attachment to this specific village as Lifta’s Palestinian refugees do.

[8] See online exhibition of the competition results more information and updates at www.seamless-israel.org.

The project for Lifta is an initiative of Zochrot, the Israeli not-for-profit organization that seeks to commemorate and discuss the Naqba1 (the Palestinian ‘Catastrophe’) in Hebrew; to witness what was wiped off the face of the earth in order to understand Palestinian pain and loss; to acknowledge the catastrophes of 1948 and 1967 and thereby form a peace-seeking Jewish-Israeli consciousness. The architecture faculty at Bezalel Art and Design Academy, Jerusalem, and FAST, the Foundation for Achieving Seamless Territory takes architecture and planning as the basis of a strategy to overcome the conflict of causality, finding methods to expose the abuses of planning and to implement the legal and the practical, localising an agenda beyond research, theory and design and with the participation of the Amsterdam based architect Micha de Haas and the architecture faculty at the TU Delft in the Netherlands.