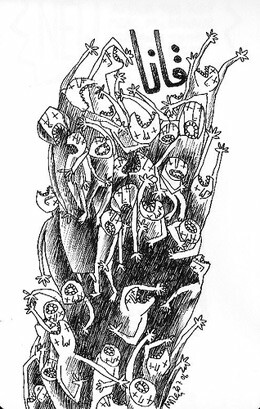

“Qana” by Mazen Kerbaj. View more of his work.

The scattered volleys and the sound signatures of different caliber bullets are tell-tale signs of a funeral procession.

But what I see in front of me on the television screen is much more disturbing. Videos of little boys and girls, all dead, being pulled out from under the rubble of a building. It is much too painful to look for more than a few seconds at a time. The faces are too vivid, too close up, too real. Anyone watching, and I know that tens of millions are watching, cannot help but feel completely devastated and outraged, especially those, like myself, who have children of the same age as the ones on the screen.

I see the word Qana on the bottom of the screen and, for a very long minute or two, I think that what I am watching is old footage of the Israeli massacre of one-hundred Lebanese civilians in the village of Qana during operation “Grapes of Wrath” in 1996.

But wait: Were not those victims burned in a fireball of bombing as they sat in a UNIFIL shelter? The children I see now are not burned at all. They are completely intact with just a fine, even coat of dust on their lifeless bodies. Then it suddenly becomes clear: another massacre at the same village, Qana, ten years later. So far, they have pulled fifty-five bodies out of the shelter, thirty of them children.

All the reports from the news agencies and all witnesses on the scene say there is no presence of Hizballah fighters or rocket launchers in the area. Why this mass killing? A case of faulty intelligence? A completely confused pilot? An errant “smart” bomb? Or, more likely, yet another abject lesson to the Lebanese in the south that they should all leave their houses and villages ahead of a scorched earth policy?

Indeed, this scenario is a recurrent theme over the past 17 days: Almost everyday a single house in an otherwise peaceful village is suddenly obliterated by a one-ton bomb from an F16. The number of victims from a single family usually ranges between eight and thirteen. Shortly thereafter, there is a mass exodus. The difference this time is that there were tens of people from two families in this large house.

On the face off it, the world has not changed. The only difference between this latest attempt by Israel to resolve festering political problems by military means is the increased intensity and pace of destruction and killing.

But something has changed.

The 1996 Qana massacre led to worldwide condemnation of Israel, to an early end to the Israeli invasion, and to the political demise of then Prime-minister Shimon Peres who ordered the strike. This time, I suspect, the US will blame the massacre on Hizballah, the Israeli military will intensify its air campaign, the Israeli public will still remain steadfast in its support its government’s war, and the world will watch helplessly as this madness goes on.

In the most fundamental sense, and unless something drastic and unexpected happens, Israel has already lost this war. All the big players know this already, though some in the Bush administration and the Olmert government remain in denial mode.

Yesterday, Nasrallah made what amounted to a victory speech and already the Arab governments and European community are re-configuring their policies to adjust. Just 48 hours after making big threats, Rice is back in the region in an emergency mission to limit the damage to Israel and to try to salvage something from the debacle.

Until that happens, Qana will remain a warning to all that military power can exact a very painful price, even in the face of defeat. Ironically, the only possible way for Israel to ensure a political turn around — to cause a rift in the Lebanese government and public opinion — has just been buried in Qana, along with the children.

Related Links

Beshara Doumani is a professor of History and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of California of Berkeley. He is the editor of Academic Freedom After September 11 New York: Zone Books, 2006.