Rawda Odeh embroidering in her home. (Photo: Rima Merriman)

When Loai’s and Ubai’s mother Rawda was born in 1948, her father, Saleem Abu Khaled al Tamimi of Hebron, was in prison for his part in resisting the British plan to partition Palestine. The boys never got to know their grandfather, because he died of a stroke in Ramallah during an altercation with Israeli guards when their mother, a student at Birzeit University then (1969), was being tried because of her activities in the Palestine Liberation Front. She was sentenced to four years in prison and spent a good part of her sentence in Ramleh prison, where her son, Loai (26), is currently being held. Ubai (19) is in Jalboun prison in the north, one of the harshest in the Israeli system.

After her release in 1973, Rawda met her future husband, Mohammad Ahmed Odeh, who was among the many well wishers converging on her home in Jerusalem after her release. The two got engaged but had to put off their wedding, because they were both jailed shortly thereafter, Rawda for six months and Mohammad for two and a half years. Mohammad is currently employed at the Ramallah water works corporation and Rawda is a pharmacist assistant at the Makased Hospital in East Jerusalem. They have two more sons, Qusai (24) and Udai (16). Until recently, Qusai was in Iceland studying mechanical engineering. Now he is back in East Jerusalem and about to enroll at the Hebrew University in order to study speech and hearing science. But first, he must learn Hebrew. As a backup, he is trying to get citizenship in Iceland. Udai is still in high school.

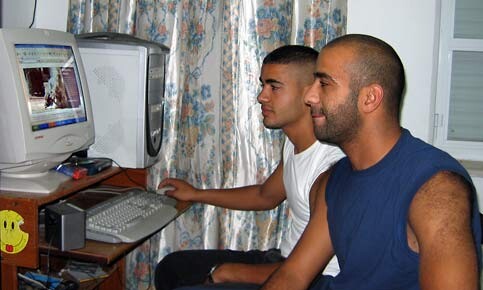

Qusay and Uday in their bedroom, checking out EI’s homepage on their computer. (Photo: Rima Merriman)

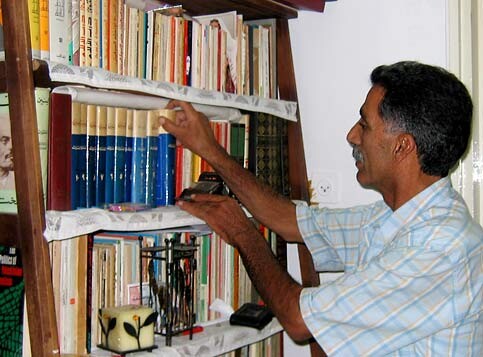

Mohammad with family books, which have shaped a lot of his and his sons thinking. One big influence is Ghassan Kanafani (1936 72), a Palestinian novelist, short-story writer, and dramatist, whose major themes are exile, national struggle and dispossession. (Photo: Rima Merriman)

Ubai was arrested at 17 when he was on his way to school. He was held (questioned and tortured) for 38 days, but had nothing to confess. The accusations against him are based solely on what others have reported under questioning. He was sentenced to 2 years and 2 months, but the military prosecutor, who believed that Ubai had the makings of a leader in spite of his youth, appealed the sentence, which was then upped to 4 years.

For four years before his arrest in 2002, Loai was being chased by the Israeli authorities and stayed in hiding in Ramallah moving from place to place. He had completed a certificate in insurance studies from Najah University and had found a job. Many times his mother would cook his meals and take them to Ramallah in search of him only to bring them back with her, because she would be unable to locate him.

When he was finally cornered, his mother was with him at his aunt’s vacant house in a suburb of Jerusalem, Dahiat al Barid. The soldiers, along with a bulldozer, two tanks plus a helicopter on top, came at 2:30 a.m. and surrounded the house. Knowing that they had targeted her son for killing, Rawda refused to let him surrender except to an officer. She stood in front of him until an officer came to take him. She continued to call out encouraging words to him, as they blindfolded and tied his legs. Loai was sentenced to 28 years in prison. He was accused, among other things, of helping to arrange passage for a suicide bomber in Jerusalem.

Loai (with the beard) and Udays photos in the Odeh home. The embroidery is done by Rawda and says: “My son/He gave his life to his country/Traitor is he who forgets him with the march of time.” (Photo: Rima Merriman)

Loai, now 26, knew what the Ramleh prison looked like from the inside, long before he himself came to be thrown in it. As a very young child, he was a regular visitor to this prison , along with his grandmother and other relatives, in order to see one of his uncles, Yacoub Odeh, who endured severe torture (still visible on him physically) and seventeen years of imprisonment until his release in the Israeli-Palestinian prisoner exchange of 1985, when 1,150 Palestinian prisoners were freed. He had been sentenced to three life terms. Now, he is active in human rights with a special interest in demolished Palestinian houses in Jerusalem. This year alone, 83 Palestinian homes in Jerusalem were demolished by Israel and 470 people made homeless as a result.

Uday Odeh with his uncle Yacoub. (Photo: Rima Merriman)

After Yacoub’s arrest in 1969, the humble Odeh home in Jerusalem, barely two rooms sheltering Yacoub’s mother, her seven children and four relatives, was demolished (his father had died in 1952 and the oldest brother, Daoud, was taken out of school to support the family). It was the third house to be demolished by military order after the occupation. The house had been built with great hardship after the Odeh family lost their home in 1948 in Lifta, a village near Jerusalem. A three-storey house next door to them was demolished and fell on top of their home. They moved to al Bireh and then to East Jerusalem and could not return to Lifta.

This time around, the family was greatly heartened when the grapevine that had been in the yard sprouted through from underneath the rubble of their demolished home. The first fruit it bore was promptly taken to Yacoub by his mother. Continuing this sad tradition, Rawda and Mohammad now carry grapes from this same vine to their imprisoned sons. The family calls it “the Resistance Vine.”

Loai and Ubays aunt and uncle Sarah and Yacoub Odeh under the Resistance Vine. (Photo: Rima Merriman)

The Israeli prison system is such that Palestinian prisoners are largely dependent on food from their families, either through food packages or through money spent at prison “canteens.” Israelis also regularly fine these prisoners by way of punishment for prison infractions. If the person fined has no money, prison officials extort the money from other prisoners who have it. During the recent hunger strike that Palestinian prisoners conducted in order to effect prison reforms for the thousands of political prisoners in Israeli jails, Loai lost 11 kg.

Loais photo in the Odehs living room. (Photo: Rima Merriman)

The Odeh rebuilt family home in East Jerusalem after it was demolished in 1969, the third house to be demolished in Jerusalem after the Israeli occupation. (Photo: Rima Merriman)

The Odeh family home was rebuilt with help from family and friends less than two years after it was bulldozed. The grapevine is still in the yard. Shortly after Loai’s arrest in 2002, the house was burgled by Israeli troops. Rawda had called her sister-in-law, Sarah, asking if she could keep her valuables at the family home (investments in gold coins that she had gradually accumulated for her sons’ education from what she earned through her embroidery) as well as her jewelry (marriage dowry).

She knew that her house would be ransacked by Israeli soldiers following her son’s arrest. Shortly after this phone conversation, which the family believes was tapped, the iron grid on the back window of the house was cut and bent to allow entrance to the house. Both Sarah’s and Rawda’s valuables were taken. The commemoration plaques the family kept of the various imprisonments of its members were carefully placed on top of the piles scattered through the two rooms that were searched. When the Israeli police were called, they showed little interest in investigating.

The family dog “Rumsfeld”. (Photo: Rima Merriman)

The family dog “Powell”. (Photo: Rima Merriman)

Mohammad Odeh, who has been in and out of Israeli prisons several times himself and knows first hand what his sons have to go through, was just eighteen when he saw Lifta for the first time. He and a group of people from Lifta took the first opportunity after 1967 to visit their hometown with the older ones telling the younger ones what they remembered of the village mosque, the village school, the village water spring, the village farm lands. Some of them had family homes still standing with Jewish families now living in them.

The Odeh family has appealed to Israeli authorities to allow Loai and Ubai to be held in the same prison to make family visitation easier, especially for Rawda, who is suffering from cancer. So far, nothing has come of the appeal. One brother remains in the far north of the country and the other in the far south.

Related Links

Rima Merriman is a freelance writer and a communications specialist. She has been working in the West Bank for the past five months.