Lebanon 2 August 2006

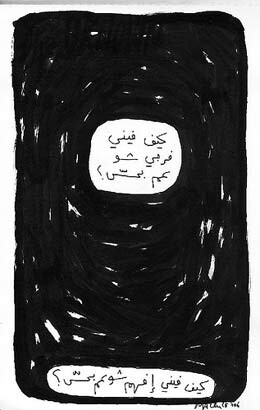

“Black”: How can I show what I feel?/How can I know what I feel? by Mazen Kerbaj. View more of his work.

I have been trying to tell my story, what I was doing, why I had been here or there, all of it, but every time I begin writing I feel like I am speaking, again, to my interrogators; I don’t like that feeling.

They ask me for my name: Perhaps I will never forget it now if I ever thought otherwise.

My place and date of birth. My religion and sect. I repeat the last one over and over: “Shu Maz’habak?”

Syriani Orthodox. I remember Elias Khouri’s novel, Yalo. Would I be tortured like Yalo? I wanted to cry. But you don’t. You don’t cry. Maybe because you still have hope and confidence in the early stages of your arrest that you should be released because you haven’t done anything wrong, and you believe they will soon realize this. So you hold onto pride and dignity, though you feel that they may be of no use here. My thoughts kept drifting; I wondered how I would behave in an enemy prison. As a Lebanese in a Lebanese prison, I felt we were all in this state of war together and should be united. This allowed me to let my guard down and give up being brave or tough, but I knew I had it in me to do otherwise, and so again I imagined how I would behave if they had no right to detain me.

But I felt they did. The details of my arrest fit the profile of a spy. I stood there, in front of my investigator, in front of the secret service (Mukhabarat), and in the presence of other soldiers, and I could only think of how stupid and naive I had been. Since my return to the country, living in Mount Lebanon had kept me at a safe distance from the real fighting in the South, and I had arrived days after most of the heavy bombing had rocked Dahye in the suburbs of Beirut. For these reasons, I did not fully comprehend the idea that we are now living in a state of emergency and that I needed to take the proper safety measures to ensure my own security. After all, this was my country and I knew who I was and that I had done nothing wrong. But one quickly learns that he is not perceived by others the way that he perceives himself, until proven innocent; and how torturous it is to prove innocence! So I was suspected and arrested.

Over the next two days that I was detained, I wondered how useful this experience would be. There was nothing to expose, I thought. I did not want to put the Lebanese government or army in a weaker position than it already was, and after all, they were doing their job. In my head I continued and still continue to blame myself, not the state. I tell myself that, were the tables turned, I would have done the same to someone with my profile, especially in a state of emergency. But something continues to unsettle me. At what point do we sacrifice our freedom for security? Did the army’s suspicion have to result in my spending a night in prison and going through this whole experience? And were it not for my connections, I may have spent more than a night in prison, maybe a week or more. I can’t help but think, maybe not in my specific case but in that of collaborators caught in the past — as some are surely innocent while others are guilty — that part of this is a way for the government to assert its presence and strength; to show in a time of war that it can hold the country together even if it can’t fight Israel directly. How do we balance freedom and security in a time of war when we need to be catching the collaborators and spies? The question weighs pregnant in my conscience. I believe the way around it is to treat prisoners properly and humanely — in much the same way that I was treated.

As my detention continued and I was transferred to a military prison, the war continued above me. In these times of war, life becomes a waiting game. You wait for the next piece of news, for the next bomb to drop, for the war to end. Being arrested in such tense and terrifying moments made me feel even more frustrated because I was, on top of everything, also awaiting my fate. Compounded with this was a feeling of uselessness as I could no longer be active on the humanitarian front — the reason for my return to Lebanon. And then the bombs fell. An army base that could easily be a target in the coming days is a terrifying place to listen to these sounds of war. Moreover, my family knew nothing of my whereabouts or my condition.

Prison. One night in Prison. No food. Only water with doubtful origins. Handcuffed for six or seven hours at a time. Blindfolded for four hours. What does that do to a person? It must do something to you. You begin to drift…

The sun

fresh air

How one can take such desires for granted.

The day and the night

knowledge of time, of the progression of the day

all of this for granted.

Movements of the hands and arms

The ability to move beyond the four walls of a room

all this for granted

to take orders

to lift your head as you please

for Gods sake, to be human!

All for granted

To be treated as a human, a human being, not an object, a reification of every aspect of your humanity, this is all taken so brazenly for granted.

And since my release, all of this has been re-imagined as I am told that I am being tracked by the US, Jordanian and Lebanese governments (emails and all). How can you live with the knowledge, and worse, the confirmation that you are being watched?

And since my release, all of this has been re-imagined as I am told that I am being tracked by the US, Jordanian and Lebanese governments (emails and all). How can you live with the knowledge, and worse, the confirmation that you are being watched? For these last few days, my world has felt like the four walls of a room. And I write this to break the silence and let everyone know that I will not be broken or defeated; I will not because I have done nothing wrong. And I will not be as I was the last few days:

No emotions, just laughter, and playing things down. How else does one deal with handcuffs, green blindfolds, dizziness, fear, indignity, and the emptiness of misery, of being alone in a cell, so sadly, sadly defeated. But I’m not defeated. I had always said I would make it to prison before I turned 30 (childish naive thoughts!). Saul Allensky writes that prison creates revolutionaries. Who knows? I think it is Life that creates them and certainly not one night in jail for a stupid mistake.

I can’t say that I was completely treated like a human being, but I was treated well, especially for someone suspected of being a collaborator with Israel. They did not hit me. In fact, I want to thank, perhaps even dedicate this, to the guard in the military police prison who offered me a Halaweh sandwich and then later offered to split his tuna sandwich, and whose name remains unknown to me. He had been to prison in his life. A compassionate man. Young, and disgusted with the war. The soldiers I met, like the rest of us in society, are conflicted about the war and have different positions. It isn’t the first time I have heard prisoners talk about developing relations with guards. My investigator also treated me well.

There were times, however, when I felt real fear. You learn quickly how difficult it is to prove your innocence, and that your story and your life may not necessarily add up for others.

Doubt. When someone doubts you, the consequences are deadly. You quickly feel the world close in. Claustrophobia and helplessness take over. How do you respond when someone says, “Who do you work for?” and you say “No one,” and they shout back, “Kezzeb!” (Liar!).

“What do you do?”

“I’m a student.”

“Kezzeb!”

Everything you say they doubt, or worse, don’t believe. “Kezzeb! Kezzeb! Kezzeb!” Everything you say is a lie. I can prove I work for someone by showing documentation, but how do you prove you work for no one? They took me from the military police investigation unit to the military police prison in which I spent the night, and then from there to the Mukhabarat the next day. That was when they blindfolded me for four hours. Ay, to see the light, to see who you are speaking to, I wished for that. The darkness destroyed me. I spoke but it was not my voice. Who was this helpless, defeated person that spoke for me? I paused, and in my daze wondered if it was in moments like these that one discovers another previously unknown character buried within the self. I felt dizzy; perhaps I passed out standing and did not know. I forgot the details of my Life, struggling deeply to retrieve them.

But it did not last long. It could have been worse. I wonder today the extent to which my safety was afforded by my family’s connections with our church, government ministers, generals and high officials in the military, or was it because I’m an American citizen? I may never know. But I do wonder, after hearing stories of the US government denying aid to left-leaning activists overseas, if they would rather be rid of someone who opposes their imperialist interests. For now, I’ll refrain from too much speculation.

I wrote these words after my release and I wonder if they still resonate:

What gives you hope, what allows you to survive is the knowledge that it could be worse.

They could hit you

and then

they could torture you

and then

they could put you in solitary confinement (or perhaps this comes before torture)

and then

they could do it all again and again.

Once you lose hope and believe your situation cannot get any worse, you have nothing left. This is when Life begins to close in on you, when all you have left to hold onto is your resilient sanity…until even that is gone.

May you never face a day in confinement. May you never have to learn the value of freedom in this barbaric way, no matter what treatment you receive. This war is ugly and dirty; by the end of it every person in Lebanon will have a story to tell. Some, like mine, are more fortunate. In the end, all we hope for is to be able to tell our stories with a gentle smile.

Related Links

Sami Hermez is a Lebanese-American doctoral candidate of Anthropology at Princeton University working on violence in the Middle East. He returned to Lebanon in the middle of Israel’s invasion of his country to stand in solidarity with his family, his people, and a just cause. He can be contacted at shermez@princeton.edu