The Electronic Intifada 21 July 2003

Click to purchase on Amazon.com

Documented are the people he meets and the scenery he finds. On the title page is a gestural portrait of a young woman with chin-length hair, leaning forward as if she was engaged in an interesting conversation. Tobocman asks, “Is she an Arab or a Jew?” The reader never finds out.

But what the reader does conclude after reading Tobocman’s text and looking at his drawings, which vary from quick gesture drawings to stylized contour drawings, is that Israelis and Palestinians have more in common than they differ. For example, on consecutive pages are portraits of a Jewish mother holding her child and a Palestinian mother standing alongside her daughter.

The role of women is one that the author is sensitive to. When first arriving to Dir Ibzia, Tobocman is advised by other Americans not to draw portraits of the women, and finds that boys, not girls, run up to him to have their portraits drawn. However, after spending a few days there and being invited into villagers’ homes, Tobocman both draws and talks with the women.

Tobocman notes their variety in attitudes towards religion and tradition, and meets a young woman who expresses frustration at her reality of having a tank in front of her house, and expresses envy of the reality of European women who get to go to discos. Another girl, Nadia, has a sense of pride in her village, but she states, “I don’t want to grow up to be one of these village women who marries and covers her head and bakes bread for her husband and has every year another child.”

Tobocman meets young Palestinian men who are struggling to define themselves in relation to their parents. Mazeed, who once had his shirt ripped by an Israeli soldier after refusing to take down a Palestinian flag from a nearby building, was beaten by his father because he thought his son was lying and ripped his shirt while goofing off in the street. Mazeed says, “That is when I realize I am really in trouble, because I am not just under occupation. I am under two occupations.” Indeed, Tobocman adds, “Mazeed was thrown out of Dir Ibzia for wearing shorts.” Illustrated is Mazeed, a skinny man, explaining his situation and wearing a tight tank top and very short shorts.

Along with some of the nuanced issues within Palestinian culture, Tobocman notes the humiliation and break down of society that is a direct result of the Israeli military occupation. Tobocman illustrates a store keeper, and explains that “Some villages are only surviving because of store owners who let folks buy food on credit.” Also commented upon is how kids in Dir Ibzia have to “sneak through the mountains to get to class in Ramallah.”

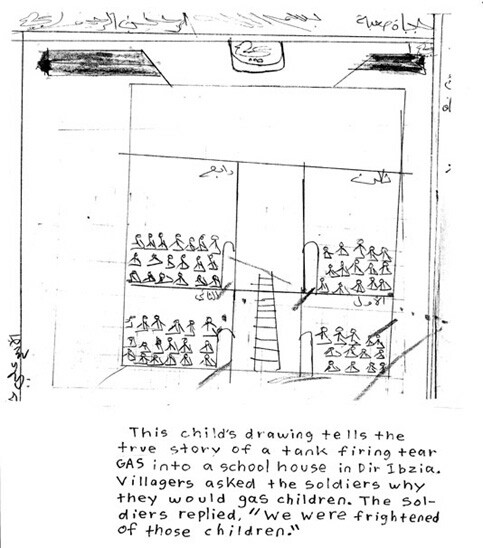

But the most disturbing of the personal experiences documented in the book is the one illustrated by one of Tobocman’s students, Ali Jawan. The child’s drawing illustrates a bunch of stick figures, presumably students sitting at their desks, being fired upon by a small stick figure in a hugely disproportional tank armed with an equally huge machine gun. Written in a different handwriting than the rest of the book (which only includes typeface in the introduction and author’s note) it is explained, “This child’s drawing tells the true story of a tank firing tear gas into a school house in Dir Ibzia. Villagers asked the soldiers why they would gas children. The soldiers replied, “We were frightened of those children.”

Although Americans are easily jaded by reports of human rights violations, Tobocman’s book renews the notion that these people are indeed “like us.” He writes that Palestinians and Israelis are “two communities at war. But they are communities. Communities where people love their children, care for their neighbors and participate in society. They are not crazy. They are not barbarians. They are not evil.”

It is worth mentioning that Tobocman traveled to the region to meet those who “have been portrayed as faceless, nameless … invisible.” He also recognizes that “in many ways, the fate of that region has been in the hands of Americans who aren’t experts, Americans like you and me.” He adds, “That’s why it’s important for us to come to a better understanding of the situation. I hope we make the right decisions.”

Tobocman invites his readers to take the first step towards understanding — recognizing that Israelis and Palestinians are human, have individual identity, individual relationships to their society, and that they, specifically Palestinians, should not be reduced to a single narrative of conflict like they are in the media.

By allowing his readers to examine the quiet dignity exhibited in the face of a Palestinian-American who returned to his homeland after Oslo, and to study the motion of an Israeli woman on a bus who, seemingly in an act of exhaustion, rests her head in her hand, Tobocman offers something that news reports, political-historical books, and the like cannot offer — an accessible human identity. And this reader, for one, is left with the urge to see more faces and to hear more individual stories and experiences.

Related Links

Maureen Clare Murphy is a frequent contributor on arts matters on both EI and its sister site eIraq. She is editor of F-News and lives in Chicago.